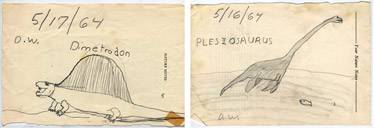

One might assume that David Wiesner was born an accomplished artist. He is a celebrated author/illustrator with numerous awards, honors, and even three Caldecott medals and two Caldecott Honors. However, when he visits classrooms and gives presentations, examples of his early work suggest otherwise. “My parents saved everything I drew, so kids can see what I did when I was five years old, seven, eleven, and so on. For the most part, it all looks like what any kid at those ages would do.”

As a child, Wiesner spent his days playing with neighborhood friends. They enjoyed make-believe activities, playing games, and exploring their surroundings: the woods, a swamp, and even a cemetery. These early adventures built an active imagination in the young boy. That imagination was further engaged during trips to the library where he would immerse himself in the wealth of imagery found in art history books and natural history books. Eventually, art became his creative outlet.

“I was always interested in drawing, and by the time I was in elementary school, everyone knew me as the kid who drew all the time.” As he continued to draw and to refine his skill, he discovered his passion was not to simply draw, but to tell stories in pictures and in sequential images. “Comic books were an enormous influence on me; it was the first place I saw visual story telling. Everything I do today I learned in comic books.”

It was during art school when a teacher and mentor, David Macaulay, demonstrated through teaching and through his own work what a picture book could be. Then, when Wiesner discovered Lynd Ward’s wordless books, he realized he had found his calling. “The more I looked at the picture-book field and realized the amazing range of work that was being done, it started to feel like a place where the things I was thinking about could fit in. I realized I wanted to tell stories, and I wanted to do it in books.”

Since his eureka moment—his epiphany—Wiesner has not stopped telling stories through images. As an author/illustrator, he begins every book with a visual stimulus and then the act of drawing sparks the ideas. “I have plenty of interesting images, but they don’t all evolve into great stories. I have to get the initial idea down and then ask: What is going on in the pictures? What is this story about? Who is it about? And that analysis, that exploration of ideas, reveals the story. Once the story has come together, then I am free to build that world with detail and nuance and humor and visually interesting things.”

“The sad thing that I often see is very young kids saying ‘I can’t draw.’ They’ve already hit this point where there is an assumption that pictures should look a certain way. I’m trying to break down those ideas and preconceptions because there is no ‘right’ way. How to draw better is teachable. What is not teachable is the idea. It is much more important for kids to draw ideas that excite them without worrying about what others think.”

In addition to body language, Wiesner also incorporated language in the form of dialogue. “Language was a big part of the story all along, but it is in dialogue you can’t read. The languages the aliens and the bugs and the cat use are different for each species. That was really neat to create an interesting visual language. I’m interested to hear if kids actually try to read it.”

This month, Wiesner begins his fall tour to promote Mr. Wuffles. He also continues to sketch ideas and to develop story lines. “I am working on a graphic novel now and I have a couple of other picture books that I’m beginning to work on. That is enough to keep me occupied for a while.”