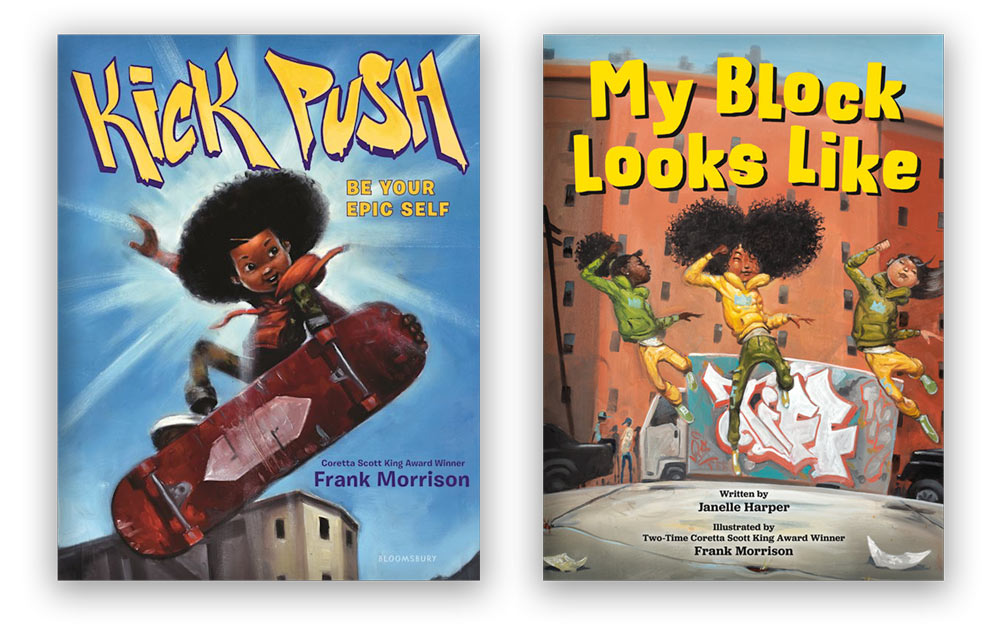

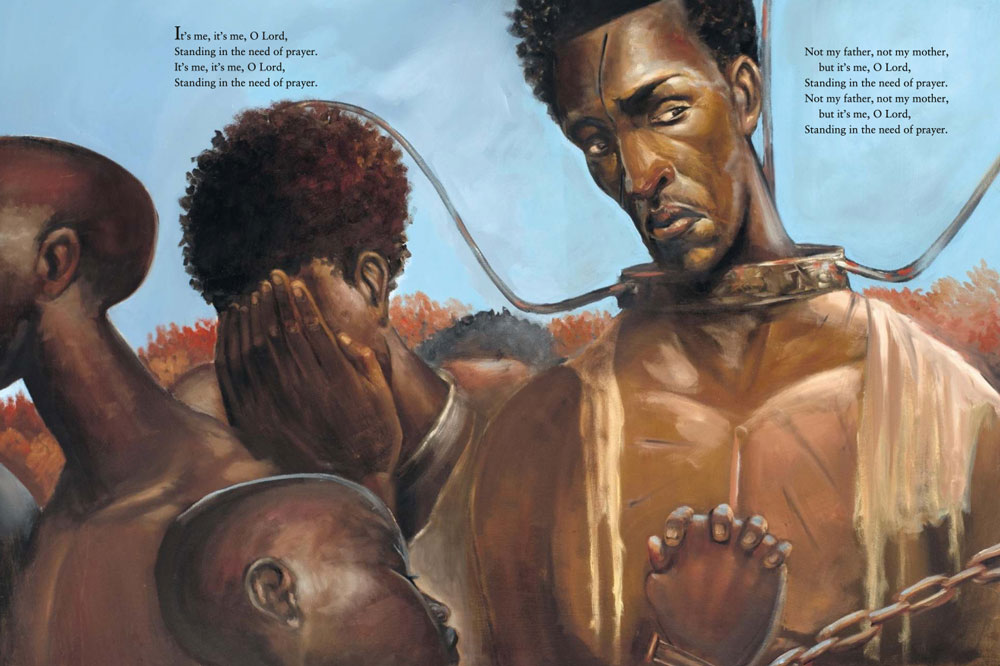

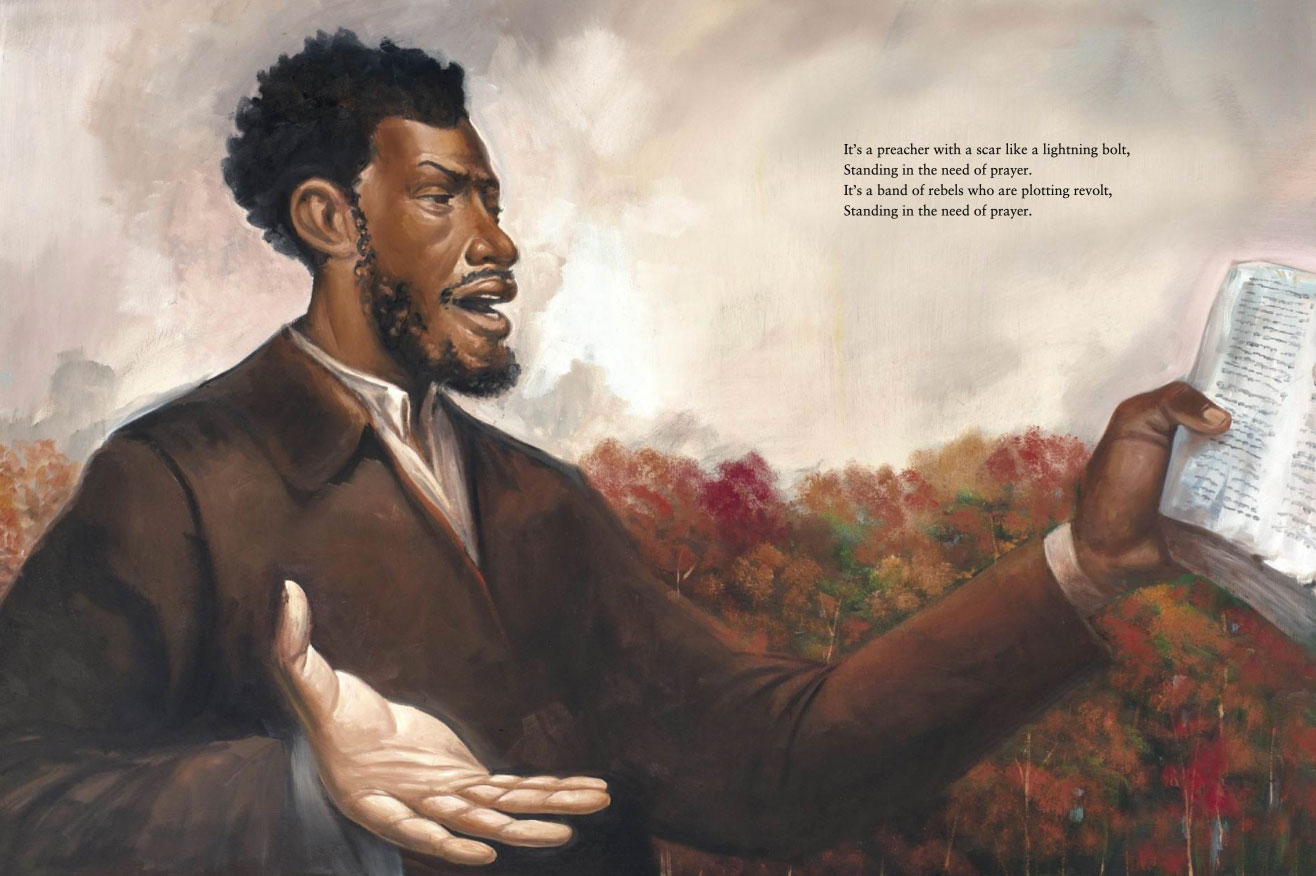

Frank Morrison’s illustrations are infused with movement—bold, jubilant, vibrating, expressive—the artwork leaps off the pages of his books. Morrison, who started his journey as a graffiti artist in New Jersey, is now the illustrator of over twenty children’s books, the author/illustrator of Kick Push (Bloomsbury, 2022), and a multiple-time Coretta Scott King Illustrator Award winner. His titles take a joyful, vibrant look at the people living within the pulsing beat of a city. His newest book, My Block Looks Like (written by Janelle Harper, Viking), is coming out January 2, 2024, and is already generating starred reviews. Morrison’s other titles offer thought-provoking explorations of Black history and culture, like the award-winning Standing in the Need of Prayer: A Modern Retelling of the Classic Spiritual (written by Carole Boston Weatherford, Crown, 2022).

Here, Morrison talks with Lisa Bullard about his focus on underrepresented people and places, making something out of nothing, and the school project that proved to be a revelation for him.

My Block Looks Like is a wonderful example of the way that so many of your books celebrate urban life. Several of your other titles, like Standing in the Need of Prayer, illuminate Black history. What thoughts would you like to share with young readers about those two inspirations for your work?

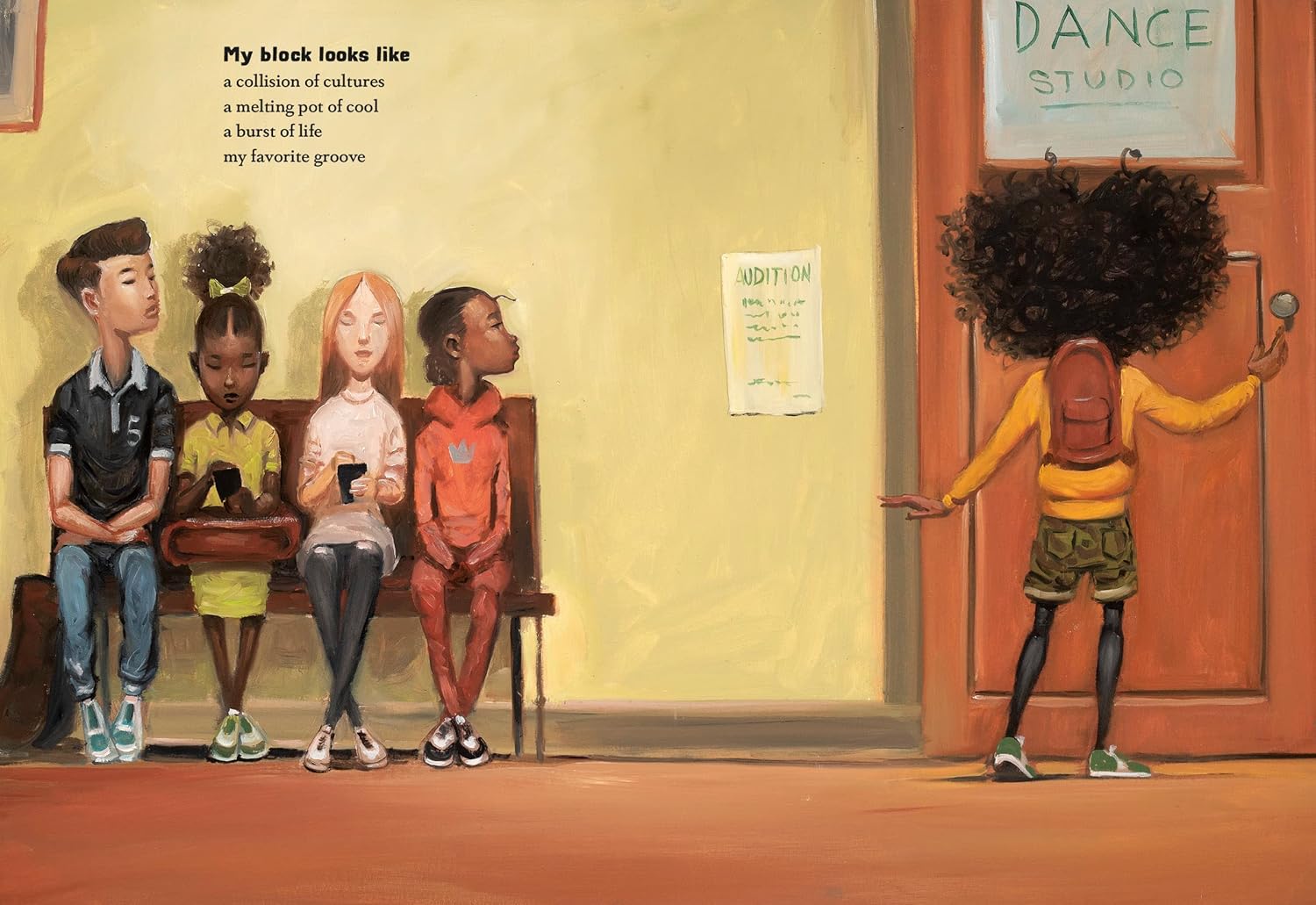

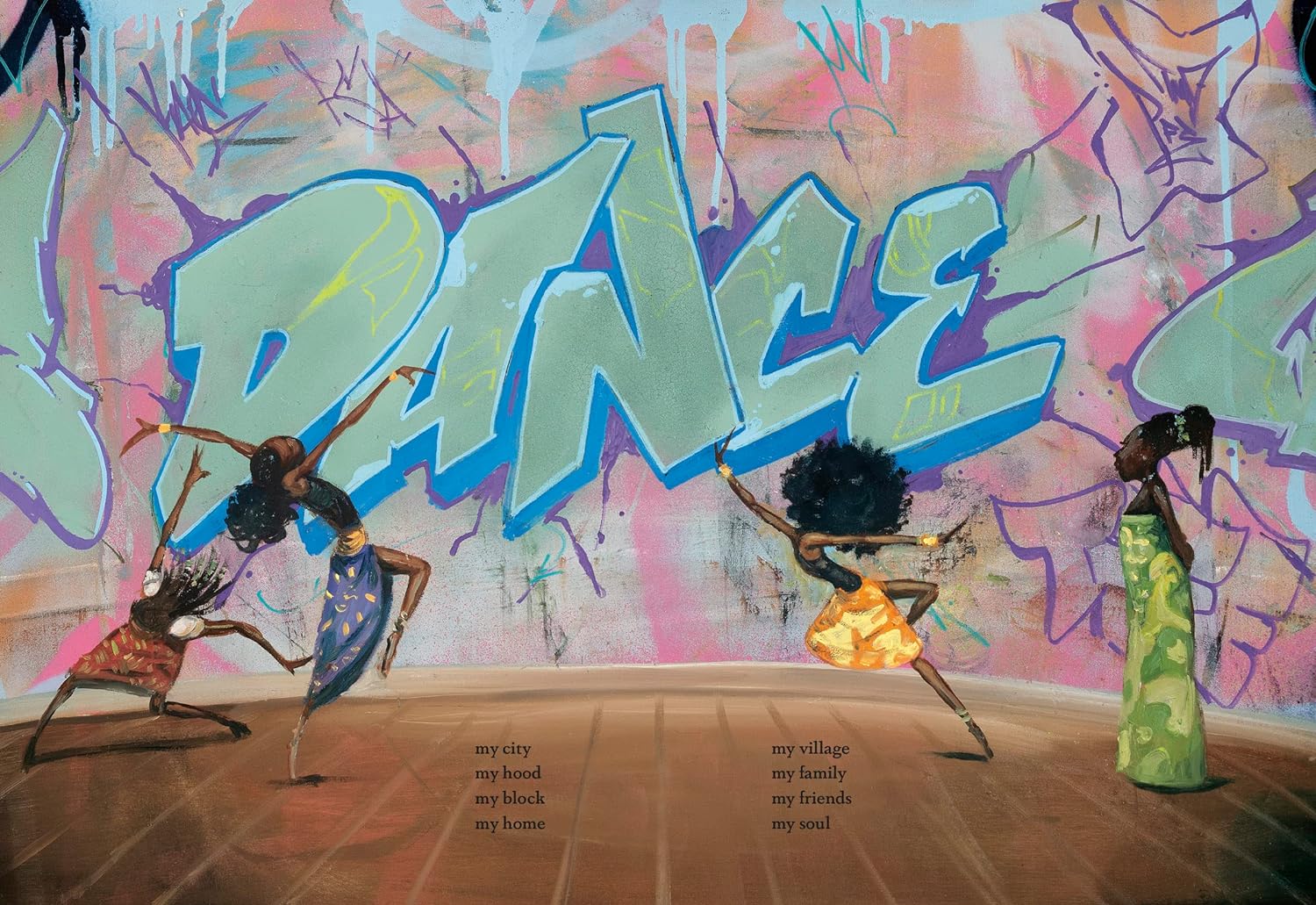

The works that I paint and the books that I choose to illustrate reflect social realism. I consider myself an Ashcan School painter. The artists of that movement focused on life in New York and on the city’s poorer neighborhoods. And so, I create images that show the underprivileged and reflect on their history. I chose to work on those two titles because I want to shine light on those who may be forgotten. The inspiration for My Block Looks Like drew upon dance battles with my daughter in my living room. Standing in the Need of Prayer took me back to the time of this TV show called Eyes on the Prize. One shows the struggle, the other shows the freedoms that came from the struggle.

I want to shine light on those who may be forgotten.”

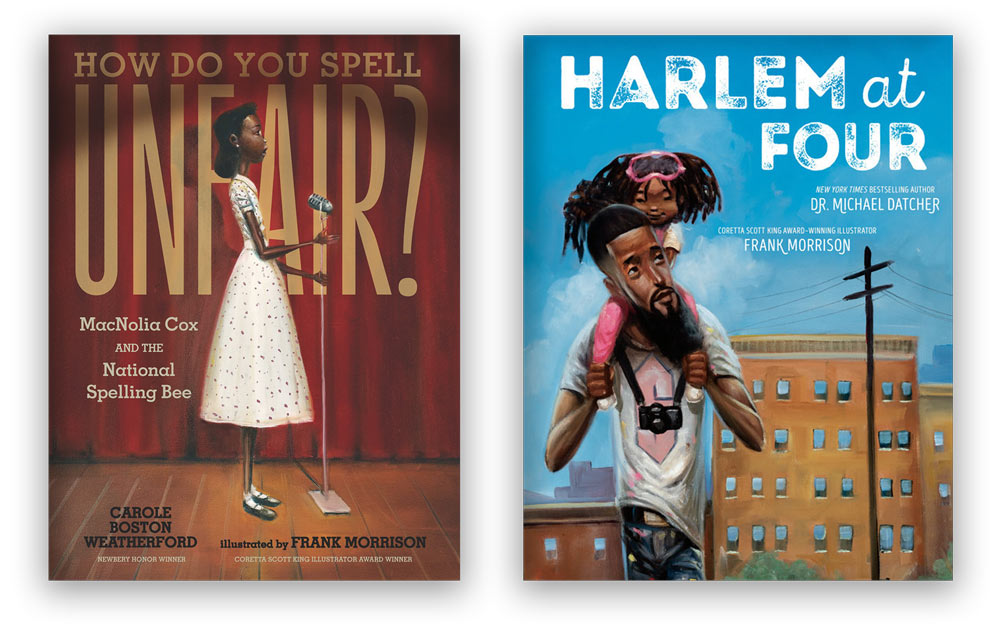

Many of your books like How Do You Spell Unfair? MacNolia Cox and the National Spelling Bee (written by Carole Boston Weatherford, Candlewick, 2023) and Harlem at Four (written by Michael Datcher, Random House, 2023) draw heavily on real people, places, and events. What is your research process like?

I have an extensive collection of books on Black history. What I don’t have, I Google. If I’m able to find a book on the subject matter, then I buy that. I’m working on a project right now where I had no idea what the subject looked like as a young adult. After researching, not only did I find a book on him, I found images in a book that I could refer to as well.

Do you have any suggestions for students who are learning how to do effective research?

My biggest suggestion to students who are learning to research is this: build your library.

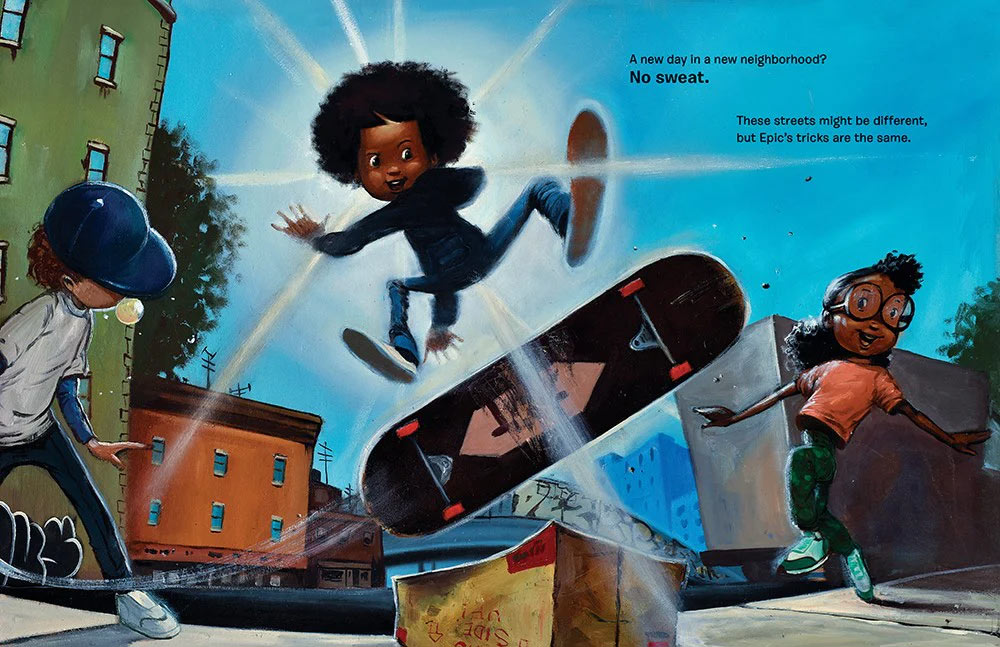

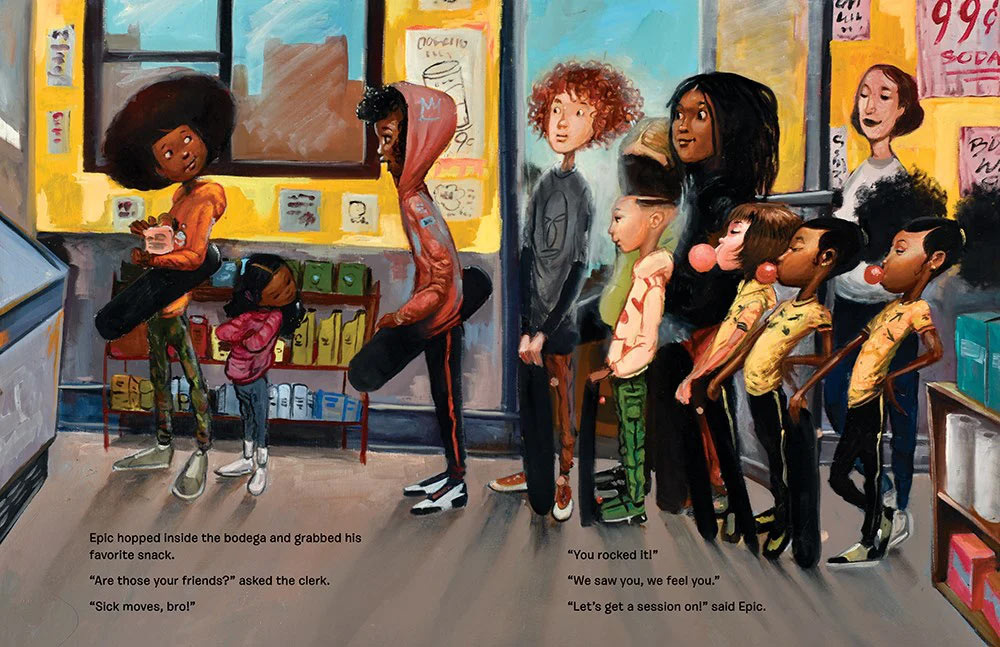

Spreads from My Block Looks Like

In a statement on your website—but also noticeably through your work—you demonstrate the fact that you highlight “everyday, underrepresented people and places.” Can you give young people some tips about how they can take inspiration from their own “everyday” environment and the people who populate it? Are there special ways that you as a creative person pay attention to the things around you?

These are great questions! I believe everyone has a God-given gift. I also believe that it’s harder for certain groups of people to recognize their creative gifts, in the sense of drawing or writing, given their economic and social situations. Being able to dream and being poor, it sometimes clashes. But that being said, rappers in the 1980s rapped about their environment. Basquiat painted his environment. Use what you have around you, whatever you have access to—even if it’s only a piece of paper and a pencil—in order to develop your talent. I photograph, take notes, and sketch everything around me, from sunsets, to buildings, to people. Just paint your reality.

Use what you have around you, whatever you have access to—even if it’s only a piece of paper and a pencil—in order to develop your talent. … Just paint your reality.”

How does your artistic process work?

First, I have to like the project, as well as find something that I can identify with in it. Then I research the subject. A book’s illustrations take anywhere between three to four months for me to produce. I have to be excited about the project for at least that long. So, I draw the sketches in a way that will make me want to come back and paint them three months later. I tend never to work on pieces that sit still. I need movement in my work, so adding certain mannerisms and perspectives to a sketch make me excited to work on that page in a visual sense when I paint.

Do you have a final image in your head from the beginning, or do the images evolve considerably as you continue to work on them?

My images do tend to evolve as they progress from sketch to final art, whether it’s the light source, color scheme, or something else.

What other details might students find intriguing about how you create your illustrations?

I sneak my daughter’s name, Tif, into every book or piece somehow. I’m a family man, so I draw a lot of inspiration from my children.

Spreads from Kick Push

You use perspective to such great effect in your art, both surprising and delighting readers with the unexpected viewpoints you present to them. Can you share some tips to help young artists learn how to incorporate perspective into their own drawings and paintings?

Honestly, I don’t know how that happened; this is how I see life. Being able to make something out of nothing, you exaggerate, and I think this shows in my work. I don’t notice it anymore; this is just my style. But I will say, the true artist’s hand is reflected in their work. If you are a dancer, a graffiti artist, then we should see that. If you love cats, we’re gonna see cat hair. If you’re a neat person, then your art will be meticulous. I can’t tell someone how to be who they are. Don’t be bound by realism, though. Let your imagination take over. I also tend to view the works not from my perspective, but from the viewer’s perspective. I keep them first and always think, What would they like to see?

The true artist’s hand is reflected in their work. If you are a dancer, a graffiti artist, then we should see that. If you love cats, we’re gonna see cat hair.”

What would you like to tell young readers about your experiences growing up? How did that time in your life inform your art and the approach you take to illustrating and writing books?

First, if I could, you can. I drew on anything I had around me. Being poor, I couldn’t be choosy. I drew the way children play video games, so for hours a day, I drew. That gave me the discipline to develop my work and skills. In 6th or 7th grade, there was a project where we had to draw on the door and turn it into a Halloween door. I wasn’t the best-dressed kid, but when my class picked me to be the artist, I realized I was still the most popular kid in the class because I could draw these Halloween characters on the door. It’s not just about what you own, it’s about your talent. I stayed thinking that way for the rest of my schooling, because you couldn’t buy talent, and so being underprivileged, my talent was priceless.

Is there a particular book of yours that was most influenced by your childhood or teen years?

My upcoming book Dragons in the Hood reflects on haves and have-nots and talent, and of all the books I’ve worked on, it is probably the most influenced by my childhood.

Spreads from Standing in the Need of Prayer

What’s your best advice for young readers who want to be artists, writers, or to pursue some other creative activity?

Know your history. Whether it’s art history, literary history, whatever the medium, know the history behind what you’re working on. Research. You have to know where styles and other elements originated from because it shows the meaning behind your work. Build a library. If you can’t afford books, go to the local library. For artists, draw every day. Paint as much as possible. For authors, find and read as many books as possible. If you want to be an author, you have to, have to, read.

Build a library. If you can’t afford books, go to the local library.”

What’s your favorite part of creating books for young people?

Being able to show the diversity of America in my books. Growing up, I didn’t find a lot of books with characters that looked like me that I enjoyed, and now I’m able to change that. So, I try to put everybody in my books.

What would you like to tell your fans about your forthcoming books?

Get ready for things that are tasty with When Alexander Graced the Table, and classic with The Notorious Brer Rabbit.

What are the best ways for educators and librarians to connect with you or to follow you on social media?

That would be on Instagram at @frankmorrison and on my Facebook page: https://www.facebook.com/frank.morrison.980.