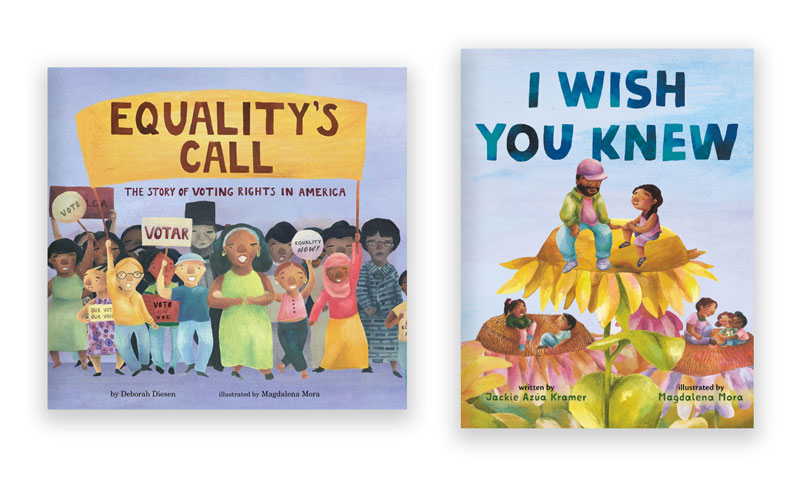

Through the medium of picture book art, illustrator Magdalena Mora is a partner in creating titles that transform current events into compelling stories. Her book I Wish You Knew (written by Jackie Azúa Kramer and also available in a Spanish Edition) focuses on deportation and a divided family, pictured from the dual perspectives of a young student and her teacher. Equality’s Call: The Story of Voting Rights in America (written by Deborah Diesen) provides insight critical to young people trying to make sense of today’s headlines. Here, Mora talks with Lisa Bullard about the collaborations inherent to picture books and about creating stories that achieve a balance between imagination and the reality of the world we live in.

Your published books deal with issues that could be pulled directly from the nightly news. When you worked on I Wish You Knew and Equality’s Call, did you immerse yourself in news coverage? Or did you find you needed to separate yourself from current events to gain some perspective on topics such as this?

That’s such a great question. It’s one that I’ve been thinking about a lot lately, and I don’t know if I’ve found the right balance yet. For both I Wish You Knew and Equality’s Call, I started by collecting as much research as possible. I come from a family of educators and academics, though, so there’s a natural instinct in me to research and over-prepare before jumping into a project.

The next few books I’m working on all address immigration and deportation to varying extents. It’s heavy. For these books, I’ve learned to collect as much research as will help me accurately tell the story. But then I take a few steps back to avoid feeling submerged in the emotions that inevitably come up after spending months researching displacement and family separation.

Hope is an overarching theme in all of these books. In order for that to come through in the artwork, I’ve found that I need to distance myself from the reality of the news stories and lean on imagination.

These are serious topics, but you still include fanciful elements in your artwork. It made me think of magical realism—is that a term you would embrace?

Absolutely. I grew up reading authors like Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Isabel Allende, Salman Rushdie, and Toni Morrison, all of whom employ magical realism in their work. My family is also from Mexico, where much of the culture and traditions are steeped in magical realism. Incorporating fantastical, dream-like elements always felt like a natural approach to storytelling.

I also think a lot of children intuitively understand magical realism, which is really just a merging of imagination with reality—that seems like a space childhood already occupies. When I read picture books to kids, they have lots of questions, but rarely do they interrogate the “reality” of the story’s world. Animals can talk; plants can grow to skyscraper-height; a person can wake up one day as a chocolate bar. Kids can suspend their disbelief for a story so long as it’s told honestly.

Picture books have always seemed like a natural conduit for magical realism. Maybe that’s why the form has always felt so familiar to me.

Kids can suspend their disbelief for a story so long as it’s told honestly.”

You’ve mentioned several authors; which picture book illustrators have especially inspired you?

I take inspiration from so many other picture book artists. Maurice Sendak, Isabelle Arsenault, Jillian Tamaki, Akiko Miyakoshi, Sydney Smith, Beatrice Alemagna, and Ludwig Bemelmans are just a few of my favorite artists; but honestly, the list is endless.

I see the illustrations in I Wish You Knew as almost an homage to the work of Gyo Fujikawa. Her soft, pastel hues and depictions of children exploring nature were a driving inspiration behind the final artwork for the book.

Your characters are richly diverse; even when presented as part of a larger group, your figures manage to adroitly capture different ethnicities, languages, religions, and body shapes. Why is it so critical that children see themselves in the pages of the books they read?

Thank you! I think that books need to reflect the reality of the world we live in. I’ve lived in diverse cities and communities, so that’s what I’m going to draw.

I don’t think about the inclusion or presence of diversity too often. To me, that seems like a given. I spend more time thinking about the accuracy and richness of that diversity, often asking myself questions like: Am I capturing clothing/hairstyles/skin tone/body language accurately? Do these characters have nuance? Or do they seem like a monolith?

I remember the feeling of not seeing myself or my community depicted in books—or worse, depicted in harmful ways. I also remember the joy I felt when I first identified with a fictional character. Those characters were as real to me as my friends and classmates. When kids see themselves in books, they’re able to recognize the beauty in their diversity, and feel connected to those with shared experiences.

When kids see themselves in books, they’re able to recognize the beauty in their diversity, and feel connected to those with shared experiences.”

To those who don’t know all that goes into them, picture books can appear to be deceptively simple packages. What do you believe is the particular strength of this form?

There are so many strengths to the picture book form. First and foremost, though, picture books are a true collaboration: between the words and the images, between the art/editorial team and author/illustrator, and between the storyteller and readers.

Illustrating a picture book requires both artistic and storytelling skills. How is approaching a series of illustrations different from creating a beautiful piece of art for someone’s wall?

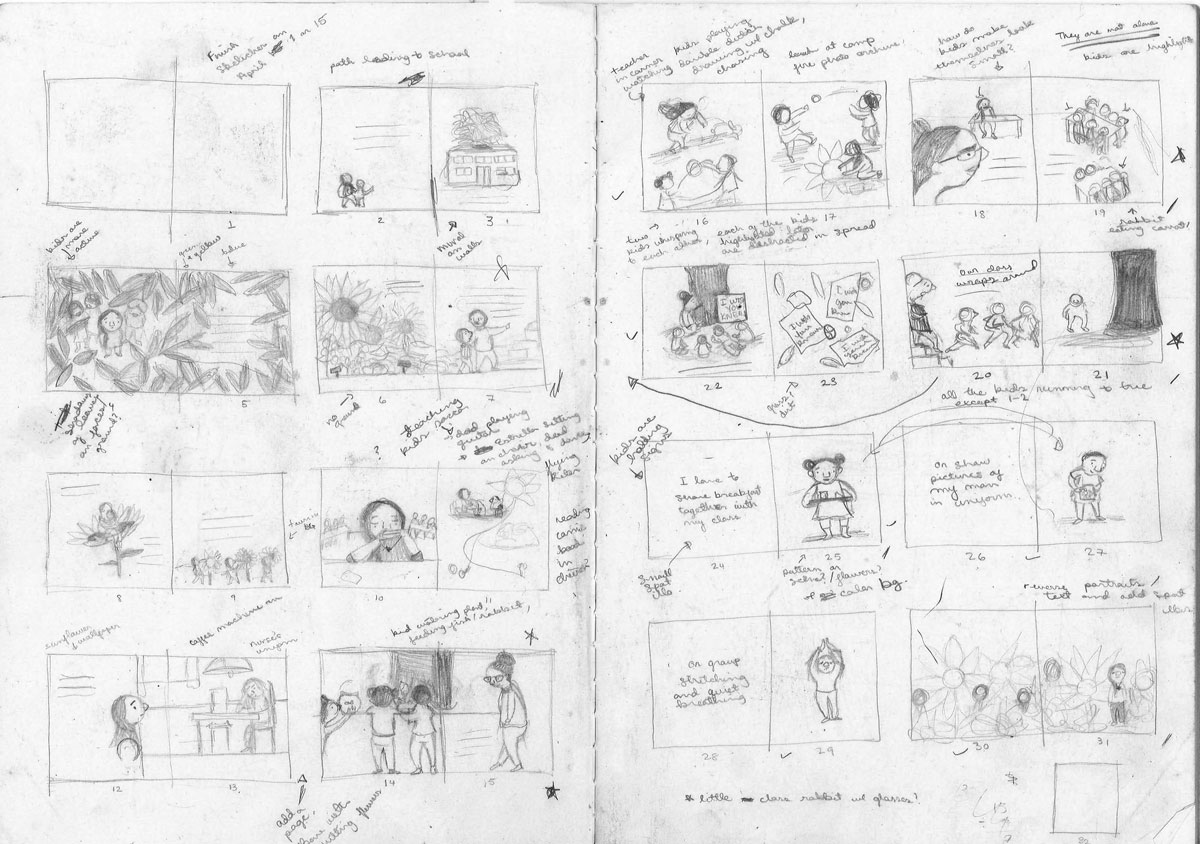

The main difference between illustrating a picture book versus a stand-alone illustration is that you have the time and space to consider storytelling elements like character development and narrative/emotional arc. You also get to build a whole world in 32 pages. I’ve often heard of picture books being described in the same vein as films or plays, and it’s so true! You can act as the set designer, costume designer, cameraman, director and—when you’re reading the book—actor/audience member.

In your experience, how long does it take to create a picture book?

Picture books often take a year or more to make. Personally, I enjoy the glacial pace of publishing—each phase allows for careful consideration. My illustration process is similarly slow and convoluted and always ends with celebration pie.

What role did art play in your own educational experience?

Even though I didn’t take many formal art classes when I was younger, I was always drawing and experimenting with art projects. I went to a large public school in Chicago at a time when the arts were being phased out. But my parents made it a point to buy me arts/crafts supplies and take my brother and me to museums and libraries. I was incredibly fortunate to grow up in a family that valued the arts and encouraged us to be lifelong learners—to follow our curiosities, even if they didn’t always align with an academic curriculum.

I was incredibly fortunate to grow up in a family that valued the arts and encouraged us to be lifelong learners—to follow our curiosities, even if they didn’t always align with an academic curriculum.”

Do you have ideas to share about how educators can bring more art into the classroom, perhaps in unexpected ways?

In the past I’ve helped classes put on performances inspired by a picture book. With a little patience and coordination, plays and theatrical productions can be a great way to explore storytelling and visual/performance art. Plus, they can be inclusive of every child’s interest/skill set—some students can “direct,” some can act, others can make props and backdrops.

I also love incorporating non-drawing art activities (i.e., cut-paper collage, vegetable printmaking, paper marbling) into classrooms. Drawing and painting can be intimidating practices, even for many adults. Using found objects like food and recycled materials can introduce more play into the art-making process and hopefully relieve students of qualitative judgements about “good” versus “bad” art.

Using found objects like food and recycled materials can introduce more play into the art-making process and hopefully relieve students of qualitative judgements about ‘good’ versus ‘bad’ art.”

Do you have forthcoming titles for us to look forward to?

Yes! I’m actually working on three books now that will be out in 2022-23 (whew!): The Notebook Keeper, written by Stephen Briseno; Tomatoes in My Lunchbox, written by Costantia Manoli-Rumfitt; and Dreaming, written by Claudia Guadalupe Martinez.

Where can readers find you online?

Website: www.magdalenamora.com

Instagram: @magdalena.i.mora

Twitter: @magdalenadraws