When I was six years old, I wanted to become a writer.

Why? Because of Charlotte.

I had just finished reading E.B. White’s Charlotte’s Web in one sitting. After I stopped crying, I immediately grabbed a pencil. I wanted to follow in Charlotte’s footsteps (spider steps?) and become a writer just like her.

A year later, I finished my first book. It was 70 pages long. It was about two best friends who got into a fight and how they eventually became friends again. I submitted it to Harper & Row because they published a lot of my favorite books back in the 1970s. They wrote back a very nice letter saying I was a “talented” writer. They encouraged me to submit a story for their children’s writing contest for kids.

I immediately ripped up that letter and burst into tears. “I’m not a ‘child writer’!” I cried, “I’m a REAL writer.” I clearly didn’t handle rejection well back then!

Who knew almost 30 years later, Harper & Row would become HarperCollins and publish my first young adult novel, Good Enough, in 2008?

But a lot happened in those years before I became a published book author.

In fact, my first clumsy attempts at writing children’s books and novels centered around animals and white human characters. Why? Growing up in the 1970s and ‘80s, Asian American history was rarely–if ever–taught at my schools. We were absent and often erased from our own country’s history. In fact, studies have shown that until recently, Asian American historical figures and important events were rarely taught in the K-12 curriculum. This lack of representation and gap in our education has led to many Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders being treated as the “perpetual foreigner” and outsiders in our own country.

This inspired me to become a journalist in my twenties because I wanted to write about the Asian American community and fill in those missing gaps. I majored in English at Yale University and then received my master’s in journalism from Columbia University in 1992. I spent the next decade as a full-time reporter for The Seattle Times, The Detroit News, and PEOPLE magazine.

One day while doing research for a different project, I accidentally stumbled across an ESPN article about Dr. Sammy Lee, the first Korean American man to win a gold medal in diving at the Olympics. I found out he was forbidden from using his town’s public swimming pool as a child because he wasn’t white. He overcame this racism to win gold and bronze at the 1948 Summer Olympics and then the gold medal at the 1952 Olympics.

I was fascinated by his story. Why had I never heard of him before? And then I remembered–it’s because Asian American history was rarely taught in our schools. I conducted more research and it led to my first children’s picture book biography, Sixteen Years in Sixteen Seconds: The Sammy Lee Story, published in 2005 by Lee & Low Books.

After that, I was hooked on writing nonfiction books for children. My other books, also published by Lee & Low Books, included biographies about one of the first Asian American movie stars, Anna May Wong, and 2006 Nobel Peace Prize-winner Muhammad Yunus. Even my first YA novel, Good Enough, published in 2008 by HarperCollins (after “rejecting” me when I was in the second grade), was inspired by my life as a Korean American teenage violinist struggling with racism in her all-white small town high school and finding comfort and power in music.

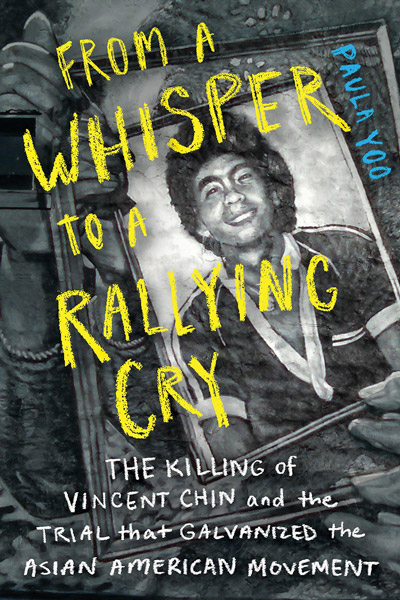

My latest book, From a Whisper to a Rallying Cry: The Killing of Vincent Chin and the Trial that Galvanized the Asian American Movement (Norton Young Readers/W.W. Norton & Co., publication date April 20, 2021), was inspired from my days as a young reporter at The Detroit News in the early 1990s.

In the summer of 1993, when I was offered a job writing for The Detroit News, the first question all my Asian American journalist friends asked was, “Are you scared of Detroit because of Vincent Chin?” At that time, it had been barely a decade since Chin’s death.

On June 19, 1982, Chrysler foreman Ronald Ebens, 43, and his stepson, recently laid-off autoworker Michael Nitz, 24, got into a fight with Vincent Chin at a club on the night of his bachelor party. The fight escalated, and Ebens beat Chin to death with a baseball bat.

According to witness testimony, Ebens allegedly shouted, “It’s because of you little [expletive] that we’re out of work” to Chin. This happened during the height of anti-Japanese sentiment in the American auto industry in the 1980s due to increased competition from Japanese import cars and mass layoffs across the country, especially in Michigan, home to the “Big Three”–Ford, Chrysler, and GM. Ebens and Nitz were white; Chin was Chinese American.

Ebens and Nitz pled guilty to manslaughter. In 1983, Detroit had one of the highest homicide rates in the country. This led to an overburdened court system where prosecutors were sometimes unable to attend all their hearings, including the March 16, 1983, hearing for Ebens and Nitz. As a result, based on limited information and because both men had never been in trouble with the law before, Judge Charles Kaufman sentenced Ebens and Nitz to a $3000 fine plus court costs each and three years of probation. “You don’t make the punishment fit the crime,” Kaufman famously declared, “You make the punishment fit the criminal.”

This shockingly lenient sentence outraged the Asian American community in Detroit. Their anger led to activism as they formed a grassroots advocacy organization called American Citizens for Justice (ACJ). The ACJ held a protest rally which ignited similar protests across the country. This national protest led to an investigation by the Department of Justice and the FBI, resulting in the first federal civil rights trial for an Asian American.

In 1984, there was one question at the heart of The United States vs. Ronald Ebens and Michael Nitz: Was this a racially motivated killing, or was this a drunken brawl gone tragically, fatally wrong? Did the two white men attack Chin because of his race, or was this a case of too much alcohol and toxic masculinity gone awry? The first trial resulted in a guilty conviction for Ebens (the man who held the bat) on one count of violating Chin’s civil right to be in a place of public accommodation because of his race, and a sentence of 25 years in prison. Nitz was cleared of both counts (including conspiracy).

Ebens, however, never spent a day in prison because his conviction was appealed on the grounds of alleged witness coaching. As a result, Ebens’ guilty verdict was reversed in a second trial in 1987. He would never spend a day in prison for Chin’s death. To this day, Ebens expresses remorse, but denies ever being racist.

But Chin’s death was not in vain–he became a symbol of justice for the Asian American community. There have been two documentaries about this case, including Who Killed Vincent Chin? that was nominated for an Academy Award for Feature Documentary in 1989. In the almost 40 years since his death, Chin’s name is always mentioned whenever anti-Asian racism happens.

In 2020, his name and story resurfaced when there was an exponential rise in more than 3,800 violent hate crimes against Asian Americans due to the COVID-19 pandemic, according to statistics from the FBI and the “Stop AAPI Hate” crime tracker provided by the Asian Pacific Policy & Planning Council (https://stopaapihate.org). One out of four Asian American teenagers have reported being verbally and/or physically harassed because of the COVID-19 pandemic, and one out of ten Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders (AAPI) have reported experiencing a hate crime or hate incident since the start of 2021.

On March 16, 2021, a 21-year-old white man shot and killed eight people and wounded one other person at three separate spas in Atlanta, Georgia. Six of the eight people killed were Asian American women–four Korean American women and two Chinese American women. Authorities did not think these killings were racially motivated. This sparked nationwide protests by the Asian American and Pacific Islander communities, similar to the same protests held for Chin almost 40 years earlier.

Although what happened to Chin was tragic, his killing galvanized the Asian American political movement and the Asian American and Pacific Islander communities. His story reminds us that we must always speak out and fight back against racism and injustice.

In writing Chin’s story, I also refer to other important milestones in Asian American history. I wrote this book for the middle school/teen audience because I want to make sure they don’t grow up like me with this hole in their education.

In fact, this has become my mission as a children’s and YA author: to fill in the gaps of our erased Asian American and Pacific Islander history. Our voices, our stories, our history, and our contributions matter. I write about our stories so history can stop repeating itself.