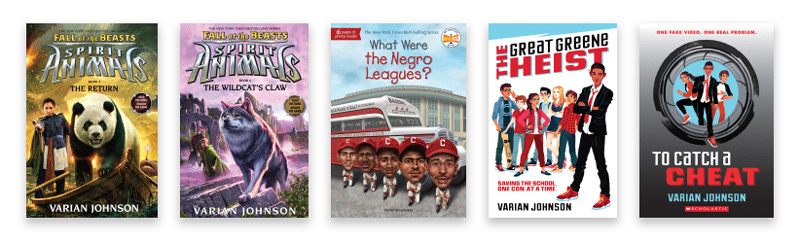

Varian Johnson’s middle-grade novel, The Parker Inheritance, was awarded a 2019 Coretta Scott King Honor as well as received numerous other accolades. The title is notable for the way it deftly weaves an exciting hidden-treasure mystery together with an examination of racism’s deep roots in the U.S. For his new novel, Twins, just published in October, Johnson takes on another challenge: his first graphic novel. Twins tells the story of sisters who discover that the transition to middle school is made even more complicated because of the challenges it poses for their relationship as identical twins. Here Johnson talks with Lisa Bullard about his own transition to writing a different kind of novel, as well as his push to populate stories of every kind with relatable Black characters.

Your first graphic novel, Twins, is brand-new, but it has already received five starred reviews. In his 100 Scope Notes blog, elementary school librarian Travis Jonker calls it “the best contemporary middle-grade graphic novel you’ll read this year.” What was your inspiration for the story?

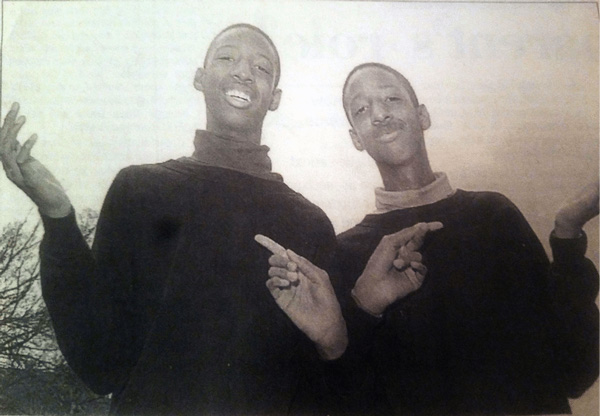

Twins is largely inspired by real-life—I’m an identical twin, born five minutes after my brother. My brother and I did everything together in elementary school. (We even dressed up as conjoined twins for Halloween—and won first place in the costume contest!) But when we began middle school, we were placed in separate classes. Just like Maureen in Twins, I struggled with that separation. It took quite a while for me to learn how to be my own, unique self.

Varian Johnson with his twin brother

The book was also inspired by my daughters. They love graphic novels, but we struggled to find books that featured Black girls. So, Twins quickly morphed from being a book just for me to become a book for all readers—a book about siblings and self-confidence, and Black love and Black joy.

I’m delighted that you use the word “joy,” because I found a really thoughtful review on Goodreads for Twins that highlights that same word. Lorie B., a fifth-grade teacher, says in part, “In every book Varian Johnson has written, I have discovered deeply developed characters, surprising plots and problems, and relatable stories to which all kids can relate. But most of all, I’ve found Black characters who are in stories not because they’re Black, but because it’s who they are. The normalization of characters of color in kidlit *not* experiencing oppression but simply being their glorious selves is a JOY to read. Twins is no exception.”

You’re one of the co-founders of The Brown Bookshelf, created in 2007 “to push awareness of the myriad Black voices writing for young readers.” Since then we’ve seen the creation of We Need Diverse Books, #ownvoices, and increasing awareness of racial disparities in the children’s book world. Do you think we’ve made progress since 2007?

Well, there are two ways to look at it. We have made a lot of progress—but we still have so, so far to go. Ultimately, I want the same “assortment” of topics and themes for Black characters that we have for white characters. I want to see more romance, more science-fiction. I want stories about Black kids set in the inner city and in the suburbs—in high-rises and on farms. I want stories about how Black lives matter, and I want stories about Black joy. I want books that reflect that my ethnicity is not a monolith; that there is a multitude of stories just waiting to be told and discovered.

“I want books that reflect that my ethnicity is not a monolith; that there are a multitude of stories just waiting to be told and discovered.”

As a child reader, were you able to find books that celebrated the kind of Black love and Black joy that you’re talking about?

I was lucky—I did discover those books during my childhood. Specifically, thanks to the works of Walter Dean Myers and Virginia Hamilton, I knew that I wanted to be a writer. Growing up, I didn’t know any writers—not even aspiring writers. But reading books about Black kids—written by Black authors—gave me permission to believe that I could someday be a writer as well.

“Reading books about Black kids—written by Black authors—gave me the permission to believe that I could someday be a writer as well.”

I imagine that you had to give yourself that same permission to believe when you decided to tackle a graphic novel, since it was a whole different kind of creative project for you. How was the process of creating Twins different than that of your other books? What was it like to collaborate with illustrator Shannon Wright?

It took me quite a while to really figure out how to write a graphic novel script—and I still think I have a lot to learn. I loved collaborating with Shannon on this project, but it took some time for it to feel natural. I’m used to finishing multiple revisions of a manuscript before anyone sees it—even my editors. But for Twins, because I wanted to get Shannon’s feedback early on, she saw the rough draft at multiple stages. To say that I felt very vulnerable would be an understatement! But I really do think this made for the best product. As we became more familiar with each other’s styles, I was able to incorporate many of her strengths into the script, such as how she portrays character emotion on the page.

That ability to capture character emotion is key for this story, since Twins features characters who are going through major transitions. Many of your readers are also at an age where they’re navigating big life changes. What is it that draws you to this theme?

Oh, I love talking about transition. I think these transition points shape so much about who we become! In one way, Twins is all about navigating rocky transitions—whether that’s a change from always being part of a group or pair to growing into your own unique self, or a shift from elementary school to middle school, or even discovering your place within a new friend group. But as much as the book is about growing into someone new, it’s also about celebrating who you already are. Maureen and Francine are at odds throughout most of the book, but despite their conflicts, they’re still sisters who care very much for each other—and nothing can change that.

“As much as the book is about growing into someone new, it’s also about celebrating who you already are.”

Speaking of rough drafts, you share on your website that The Parker Inheritance went through 15 drafts and generated the longest editorial letter of your career—21 single-spaced pages! I know many students approach the revision process with dread. Do you have any wisdom to offer educators who are looking to give their students a more positive outlook on revising?

When I first started my career, it was very hard for me to finish a first draft of a book, because my writing was never as good as all the amazing books I was reading. And then I realized—of course it’s not as good—it’s a first draft! It’s supposed to be bad! I’ve come to the realization that my first drafts are just for me. Usually, I’m the only one who reads them (except for Twins). It’s me telling myself the story. It’s during revision that I really begin to shape the story for my end reader—whomever they may be. It’s in revision that I polish the manuscript and try to make it the best book that it can be.

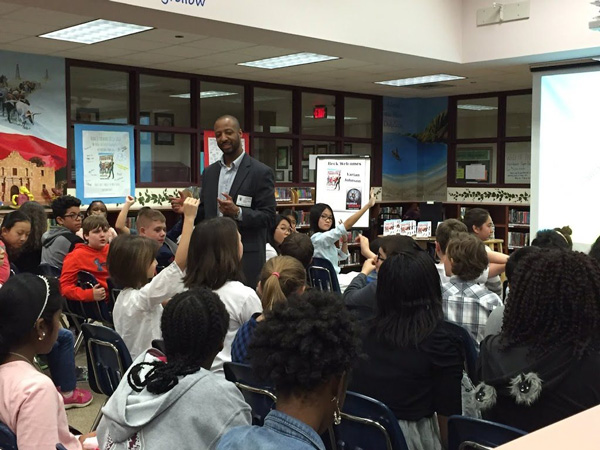

Varian Johnson visits a group of high school students in Katy ISD

Twins hasn’t been available long enough to become a classroom favorite yet, so I want to give a nod to how popular The Parker Inheritance has become with educators. On her mstamireads blog, Ms. Tami offers this endorsement: “[The Parker Inheritance] would be a great classroom companion to units on Black history, social justice, and discrimination (both racially and gender-motivated).” How else are educators or others sharing that novel with young readers?

I’ve been pleasantly surprised with the number of communities (whether that be a single school or an entire state) that have used The Parker Inheritance as an all-community read. As you noted, the book covers many topics, which in turn offers many access points for discussion. I’ve found that the book is popular with elementary school students through adult readers. And when we can get grandparents, parents, and kids talking to each other about the same book—that’s when the magic happens, and when readers can best relate fiction to real life.

What’s the best way for readers to get in touch with you? Where are they most likely to find you on social media?

I love hearing from teachers and readers—but I’m not the best at replying to emails, especially when I’m under a deadline (and I’m juggling three right now). But they can always drop me a note on Twitter at @varianjohnson or Instagram at @mrvarianjohnson.