Early on, author Matt de la Peña was labeled a poor reader by teachers who felt he was not meeting learning benchmarks. That experience deeply impacted him and led him to avoid reading until a serendipitous experience with a college professor many years later. Today, that “reluctant reader” is the 2016 Newbery Medalist and a champion for kids who have few opportunities for success. Here, de la Peña shares with Mackin’s Amy Meythaler a bit of his life’s story and his mission to write the wrongs.

Keeping It Real

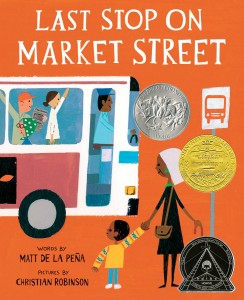

Sometimes it is easy for readers and fans to elevate favorite authors above human status. It is difficult to remember that a famous person may not have always been so. As a much-admired author of award-winning books, including the 2016 Newbery Award for Last Stop on Market Street (G.P. Putnam’s Sons Books for Young Readers, 2015), what was childhood like in your home?

Sometimes it is easy for readers and fans to elevate favorite authors above human status. It is difficult to remember that a famous person may not have always been so. As a much-admired author of award-winning books, including the 2016 Newbery Award for Last Stop on Market Street (G.P. Putnam’s Sons Books for Young Readers, 2015), what was childhood like in your home?

I had a good childhood because I had a great mother. We didn’t have much, and I distinctly remember her sitting at the kitchen table every Sunday, trying to decide which bills not to pay for that month, but she was an incredible believer in her three children.

Did your mother encourage you three to read? Do you remember her reading to you?

She read to us when we were little, but as we got into school, she started working a second job. Without her nudging, reading sort of fell away. From that point on, I only read what I had to read for school (though I can’t say I always read that either). I had to rediscover reading in college.

It seems strange that a writer would shy away from reading for so many years. Beyond the lack of encouragement at home, what happened to make you hesitant to read?

I struggled as a reader early on, and I was at a really, really bad school. I was more worried about self-preservation than academics, and my grades suffered. The teachers wanted to hold me back, and the reason they gave was, “Matt can’t read.” This was a devastating blow to my perception of myself. It took many years for me to begin to view myself as smart again.

Finding a Good Fit

As one who was labeled while a young student and felt unintelligent because of it, what is your opinion of descriptors such as “reluctant reader”?

It’s kind of unfair to label a kid a reluctant reader just because she isn’t feeling The Scarlet Letter (Ticknor, Reed & Fields, 1850) in class. I feel like educators who look at students as individuals—and I mean really stop to “look” at them—can change lives.

“When a book fits, you see the value of reading.”

So what do you recommend educators do to help kids who just are not interested in reading?

I really think it’s about finding the right books for a kid. I personally responded to books with diverse protagonists, especially Mexican-American characters. The stories felt relevant and inspiring. For me that kind of a book was an invitation to literacy. I think it’s important to treat kids as individuals who require books that offer specific literary invitations. For me it was diversity and sports; for another kid it might be science fiction.

Reading challenges aren’t just limited to kids. Your own dad came to appreciate reading later in life. How did that happen? How can family and friends support young adults and mature adults who have literacy challenges?

I think most reluctant readers/non readers simply have yet to be exposed to books that “fit.” Looking back, I think my dad gave books a chance as a way to connect with me. I was going down a road of literacy, and he wanted to meet me there. So he invested. But it’s also important that the first few books I handed him were culturally relevant. When he read One Hundred Years of Solitude (Harper & Row, 1967) he felt echoes of his own background. Of his parents’ backgrounds. And he was hungry for that exploration of his own heritage. The book fit. And when a book fits, you see the value of reading. And you develop a hunger. And once he had the hunger, he gobbled up all books, including stories that had nothing to do with himself.

In speeches and other interviews you have talked about the impact poetry has had on you as a reader and writer. What is it about poetry that made it so pivotal to your development?

Most writers come to writing through reading. For me it was the opposite. I came to reading through writing. Even though I wasn’t a reader, I had this deep desire to understand myself. And writing poetry (for me) was an attempt to make sense of things. Interestingly, I think a lot of folks like me are a good fit for poetry. We aren’t reading books, but we’re reading life. We’re observing. And poetry is a natural place to lay out your observations. And some kids are just naturals with sound.

Making a Difference

Even though you had some negative experiences in school, I’m sure there must have been positive experiences, too. Do you recall a time when one of your teachers made a positive impact on you? If so, how did it affect your self-esteem, goals, and future?

I often say that the true gift of a great teacher is humility. What I mean is, some of the best moves teachers make don’t pay off until way after the student has moved on. Here’s an example of something a teacher did that may have indirectly lead to me becoming a writer (and I’ve never been able to thank her because I haven’t been able to track her down).

At the end of my junior year she handed out the English final to everyone except me. She then came up to me with a dozen blank sheets of paper and whispered in my ear, “I gave you an A on the test. All I want you to do is write whatever comes to mind for the next two hours.”

I thought she was a weirdo at the time. But, hey, I got an A. So I wrote a story. She held me aside at the end of class and asked, “Do you know why I did that?” I shook my head. “Because you’re a great writer,” she said. “And you don’t know it. And I was so excited to see what you would come up with if you had two straight hours to write.”

I was baffled by this at the time. But a couple of years later I was in college, trying to decide what I should focus on besides basketball, and I thought of her words. And I took action in that direction.

You mentioned that you had to rediscover reading when you were in college. Was there a specific event that occurred prompting you to read or did it just happen naturally?

You mentioned that you had to rediscover reading when you were in college. Was there a specific event that occurred prompting you to read or did it just happen naturally?

I had a professor in college who introduced me to The Color Purple (Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1982) at the perfect time, and I wasn’t even in her class that semester. But she remembered me. She felt like I was worth the extra effort. And because of her passion, I wanted to really try to engage in a book. And it changed my life.

I connected with the poetry of “broken” English in The Color Purple. But Celie’s experience also put my own life struggles into perspective. And most importantly that novel made my heart ache, and I realized that I had a great hunger to “feel.” Books, I realized, could become my secret place to feel.

After you graduated from college with your undergraduate degree, you took a job in a group home. It seems like an unconventional choice for employment.

Before I went to grad school for creative writing I spent two years working in a group home in San Jose. I was a counselor (I majored in both English and Psychology as an undergrad). I learned a lot about the system those two years. I observed the powerful reality of race in this country. Ninety percent of the residents were of color. And most of my private college was white. And the kids in the system had the same hearts as the kids in all my classes. They just didn’t have the same opportunities/options. That devastating injustice is in the margins of every paragraph I’ve ever written.

Discovering the Career Path

So when did you begin writing seriously and how did you break into publishing?

I started seriously writing fiction during undergrad and during those two years I spent working in a group home. Then I went to grad school for creative writing where I started working what would turn into my first novel, Ball Don’t Lie (Delacorte Books for Young Readers, 2005). I got an agent quickly but a handful of publishers passed on the manuscript before it was acquired by Random House. Folks didn’t know if it should be acquired as a YA title or an adult title. When it was bought by a YA imprint I had to tone it down a bit. I was lucky. The whole process didn’t take too long. At the time, however, those eight months or so felt like an eternity.

You said that you write about the injustice you saw so vividly in the group home. In your books and short stories, it seems like the characters are trying to come to terms with who they are and where they belong. Are you trying to send a message to readers through your writing?

I wish I could pretend that I have some grand plan for material I think readers need to be exposed to. I don’t. I write what I see. I plagiarize the world. I listen. I remember. I explore things buried deep inside my psyche. I don’t ever go into a story thinking about readers. I go in obsessed with a character. I then explore that character in a challenging but respectful way. And I try to go all the way. If I don’t take it all the way I feel like I’m punking out as a writer. I may be wrong in a general way with some of the thematic roads I take. But that doesn’t bother me. Not if it’s a valid exploration for my character. Good writers should never go in with a message, but they should come in with a unique point of view. I think this question kind of reveals mine.

Do you ever write yourself into your books or use writing as therapy to process thoughts, reactions, and the past?

Do you ever write yourself into your books or use writing as therapy to process thoughts, reactions, and the past?

I love this question. I think I write to try and figure things out. For example, most of my work explores the life of a mixed-raced kid. I think this is true because I’m still trying to piece together what the mixed experience means for me. I write about kids growing up in working class families because I want to understand my own working class experience. So I mine myself quite a bit. But I also mine everyone around me. My poor parents have been examined dozens of times. People I’ve met. Friends. I mine characters written by others. I’ve even mined kids I’ve met at school visits. It’s really a bad idea to share anything interesting with me. It could end up in a book.

Where do the names and nicknames of your characters come from? Are those people you know?

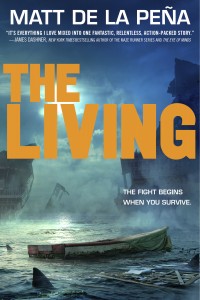

Sometimes I try to use traditional names. But it never works out. I think it may come from the pick-up basketball culture. If you play with the same guys all the time, they’re eventually going to refer to you by some kind of nickname. The same thing happens for me with character names. “Sticky” is the only name that just appeared on the page, without much thought. “Shy” was pulled from a failed novel. The original Shy was a singer-songwriter. I loved the idea of a performer who was afraid to perform. But the novel failed. So I stripped Shy out of that book and placed him into The Living (Delacorte Press, 2013). He’s no longer a guitar player, but his personality is still the same. I love names. I love how names can shape a character.

Influential grandmothers seem to make recurring appearances in your books.

I’m really big on respect for those who come before you. My own Mexican grandmother was the matriarch of our family. She shaped me quite a bit. She even took me in for a stretch during high school, when things weren’t so good between me and my old man at home. I don’t write books where the adults have all the answers, but I do write books where the young folks listen respectfully.

Focusing on Diversity

Your novels and stories seem to center around fiction featuring the Hispanic community and culture. Do you feel that you write for a specific audience?

I don’t have an intended audience, but my books seem to be an invitation to a few demographics. Hispanic kids connect quickly, and I love that, but I’m crazy moved when a reader from any group connects with one of my stories.

A Nation’s Hope: The Story of Boxing Legend Joe Louis (Puffin Books, 2013) is a departure from your usual fare. Why did you choose to take on a nonfiction project and why one about an African American?

I love when a sporting event transcends sport. Here was the first time in our history when white America was openly rooting for a black athlete. The actual boxing match was a big deal, of course. But the social/cultural relevance of that match was far greater. I was raised in a sport. And I’m always looking for opportunities to tell important stories that just happen to take place on a playing field.

“Great books go beyond race.”

What is your take on the We Need Diverse Books movement? The conversation about needing more diversity in young people’s literature has really exploded over the past few years. Do you expect this will result in an increased variety of races and cultures represented?

I think things are changing, yes. They better be changing. Because Future America will be a diverse place with a hunger for stories that feel true. If the publishing industry fails to provide diverse stories it will get its ass kicked by other mediums. Also, this is another important nuance to consider: when it comes to diverse stories I’m not advocating for “instead of,” rather “but also.”

Authenticity of voice is also coming to the forefront of the conversations surrounding diversity in literature. Why is this so?

Authenticity of voice is also coming to the forefront of the conversations surrounding diversity in literature. Why is this so?

I’ll tell you this, teen readers can smell a rat. If you’re telling a story from the outside, you better be great. And there are a ton of great writers who can pull it off. But I don’t think there’s anything more powerful than reading a story that reflects oneself written by an insider. There are little nuances that will hit home in a visceral way and cause a kid to really take ownership of that book and reading experience.

What are good examples of authentic voice?

When I read The House on Mango Street (Arte Público Press, 1984) it just struck me as absolutely true and personal. It felt like a secret passed between cousins. Have you ever read Bud, Not Buddy (Delacorte Books for Adult Readers, 1999)? Wow, now that was written from the inside. How about Inside Out & Back Again (HarperCollins, 2011) by Thanhha Lai? It comes from deep, deep inside that world and experience.

Your books are so raw and real, and young readers have really responded. But adult readers are more of a mixed bag. It seems either they love your books or they really don’t. Mexican Whiteboy (Delacorte Press, 2008) was a banned book while Ball Don’t Lie was made into a movie. How do you feel about this expanse of opinion?

Most books are banned without the banner ever having read the book. The banner is alerted to a section or experience in the book and all context is disregarded. I think the banning of a book is both a badge of honor and an incredible travesty. It’s an honor only because it means folks are listening to your voice. It’s a travesty because someone’s real-life experience is being deemed too reprehensible for “normal” people.

Making Connections

Other than working with editors and the occasional movie director, it seems that writing is a solitary profession. How do you keep grounded and connected with others both personally and professionally?

Sadly, sometimes I’m not super connected to others. I kind of just work on my stuff and then hang with my wife and little daughter. I love when I get to hang out with other folks at conferences, but when I’m home I’m really boring. Reading keeps me connected more than anything else.

Speaking of conferences, I believe I read that you had recently sponsored a teacher to go to the NCTE (National Council of Teachers of English) annual convention. What prompted that?

I was awarded the 2016 NCTE Intellectual Freedom Award–a huge honor–and with it came a free registration to the conference. My publisher was already covering my registration, though, and I didn’t want it to go to waste so I started thinking I could give it to a teacher. But then I thought about how expensive it is to pay for a flight and hotel. A teacher shouldn’t have to cover that herself. So I decided to give one teacher the free registration plus a thousand dollars for travel and hotel.

We Need Diverse Books helped me search for the perfect teacher to sponsor. When I met her at NCTE, I felt this crazy rush of pride. She was so excited about all the new things she was learning, and she couldn’t wait to take them back to her school. I think teachers are amazing humans, and the fact that I was able to assist in some tiny way was a powerful experience. I’m really hoping to do it again next year.

Living the Literature

Will you share a bit about your writing space and habits? Do you have an office? What is your daily routine? Do you have a set time for writing? What are the mechanics of your work? How do you know when you are done for the day?

On a normal, ideal day in Brooklyn I write at an office by myself. I get there by 7am and leave at 3pm. I have a hard stop at 3pm because I have a two-and-a-half-year-old and I get to hang with her solo from then until 6pm, when my wife gets home.

I start by reading a few paragraphs from my all-time favorite novel, Suttree (Random House, 1979) (I’ve read it at least 10 times and I’m never NOT reading it). Then I dive in. Seventy-five percent of my writing time goes to revising. Even when I’m working through a first draft. And I always end by writing a to-do list for the following day. Unfortunately, I’m on the road a lot, so I have to write in hotels and on planes, which is a challenge. And this year I’m spending January though June in San Diego (because I’m teaching at SDSU), so I’m trying to find a new routine.

In terms of mechanics, I write picture book drafts out by hand and I write novel drafts straight into the computer. But I do a ton of work in journals. I jot down notes, write loose chapter outlines, etc. I usually do more note-taking later in the day, too.

So in addition to writing, you are also an instructor? Why did you choose to teach and what classes do you offer?

I’ll be honest, you don’t teach in a low residency program to get rich. I teach at Hamline University–and this current semester at San Diego State University–because I really love fostering young talent. It floors me to see a hard-working emerging writer find her voice. And selfishly, I love learning from the students and my fellow instructors. I get to hear lectures from folks like Gene Luen Yang and Laura Ruby and Gary Schmidt and Anne Ursu and Swati Avasthi. Are you kidding me? I learn so much through teaching—way more than I ever learned in my MFA program.

In all of your experience and learning as an author and professor, how do you now judge writing? What makes good literature?

I think the key thing you need to learn to be a good judge of great writing is this: there is no one right way to do it. Success is finding one’s own voice. And to me a failed writer is a writer who believes he’s mastered writing. I’ll pass on that guy’s book every time.

With your busy schedule of writing and teaching, do you still make school visits? What do you share? Are you talking about your writing process?

I still make a few school visits per year. If it’s an underprivileged school I focus on college and the power of literacy. I feel like I’m speaking to a long ago version of myself. If I’m at a more privileged school I stick to literacy and writing. I love both types of visits, though it is kind of special to hit the schools where the kids get all my jokes.

“I think teachers are amazing humans.”

Are you working on writing any new books? What can readers look forward to seeing from you in the near future?

In the next two years I have three picture books coming: Carmela Full of Wishes (illustrated by Christian Robinson), Love (illustrated by Loren Long), and Miguel and the Grand Harmony (a companion to Pixar’s upcoming movie about the Day of the Dead called Coco). My next YA also comes out about a kid who’s about to be the first in his family to go to college. And I’m currently writing the YA version of Superman, which has been a real trip. So lots to come!

You have participated in numerous interviews. Is there something you wish people knew about you but no one has thought to ask?

There’s an undercurrent to all the stories I want to write. That the world is an incredibly beautiful place and also an incredibly sad place. And I think that’s okay. But folks never ask about the sad stuff. I’d tell them that I kind of believe that sadness is the very air we breathe. And I kind of believe that’s okay. My stories sit somewhere in all that sadness. And I think it’s beautiful. (Wow, I’m lucky no one ever asks about that. My answer makes me sound like a self-important weirdo.)

What is the overarching message you want readers to come away with after they read your books?

I want readers to feel something. That’s the most amazing part of reading for me.

Who is Matt de la Peña?

Matt de la Peña is the New York Times bestselling, Newbery Medal-winning author of six young adult novels: Ball Don’t Lie, Mexican WhiteBoy, We Were Here, I Will Save You, The Living and The Hunted. He’s also the author of the critically acclaimed picture books A Nation’s Hope: The Story of Boxing Legend Joe Louis (illustrated by Kadir Nelson) and Last Stop on Market Street (illustrated by Christian Robinson). Matt de la Peña received his MFA in creative writing from San Diego State University and his BA from the University of the Pacific where he attended school on a full basketball scholarship. De la Peña currently lives in Brooklyn, NY. He teaches creative writing and visits high schools and colleges throughout the country.

And the Newbery Medal Goes to…

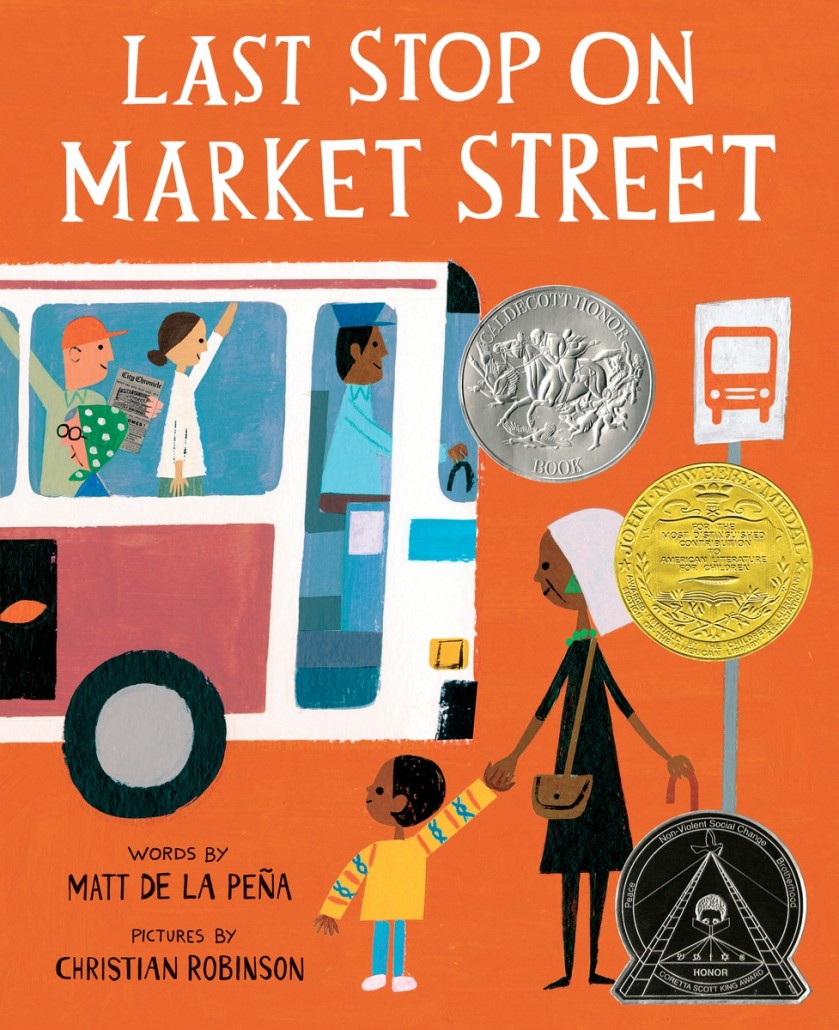

You were awarded the 2016 John Newbery Medal for the most outstanding contribution to children’s literature for your book, Last Stop on Market Street. It seems all Newbery medalists have a “call” story. What is yours?

I was sleeping in a hotel room in Minneapolis (we were at residency at Hamline). I had just turned in a first draft of my forthcoming novel, and I was feeling pretty damn happy. And then I got a call at like 3:30am and the man on the phone said Last Stop had been awarded the Newbery Medal. And I cried. And it was the first time I’d cried in over 20 years. And I don’t think it’s because I was so happy (though I was definitely happy). I think in that moment I felt like I’d been forgiven for all my mistakes as a writer. And I felt like I’d been “seen.” And I think humans have a deep, archetypal need to feel seen.

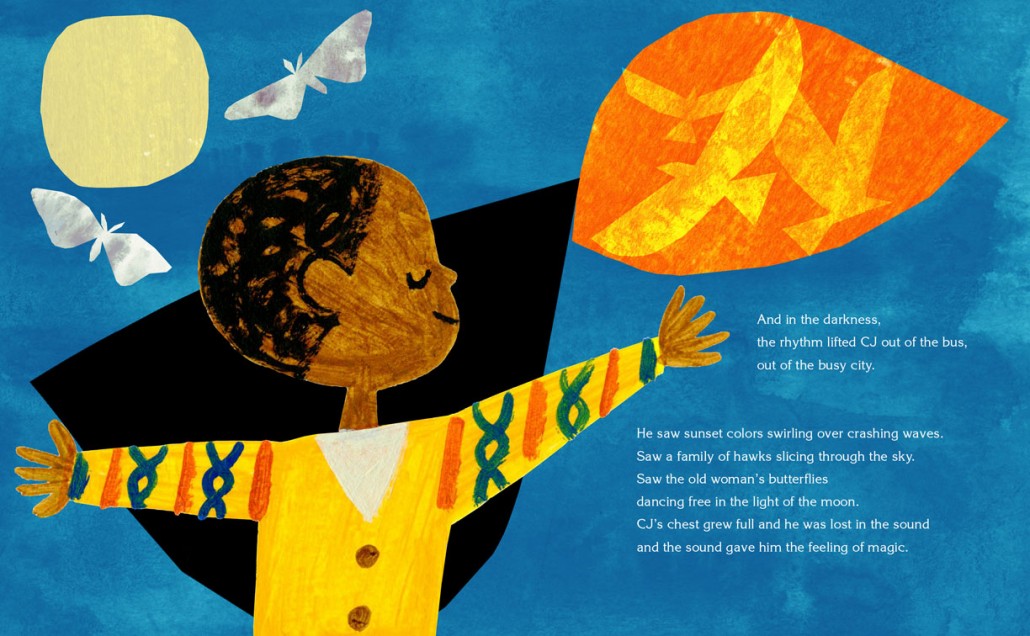

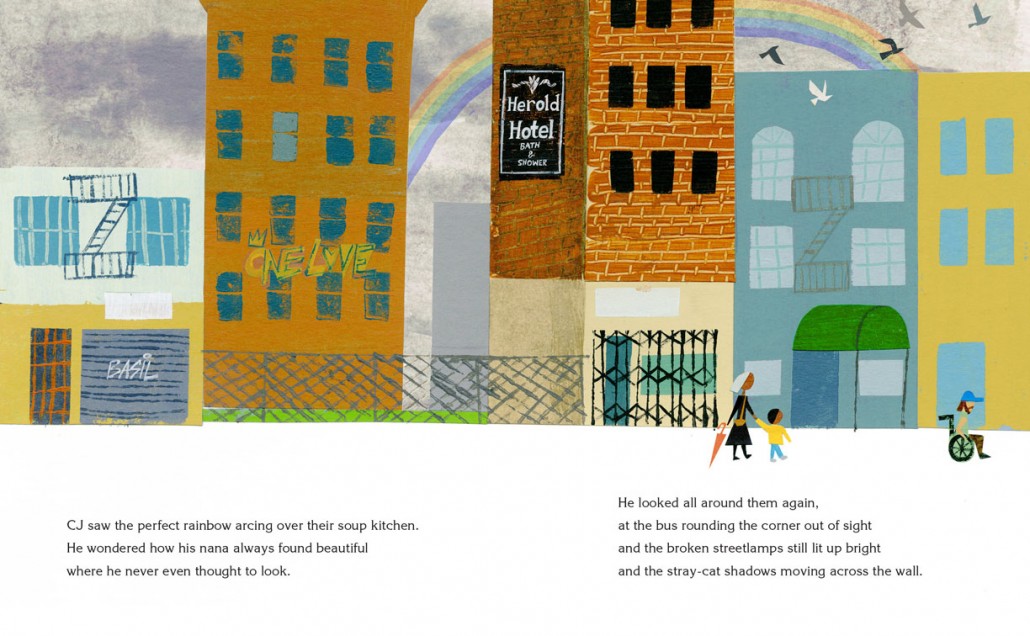

You have written several novels, essays, and short stories. Yet you received the Newbery Medal for a picture book. What, in your opinion, made this book stand out?

I think awards are incredibly, insanely subjective, to be honest. So it’s hard for me to try and put myself in the shoes of the committee. I will say this: I think I wrote an important working-class poem about seeing the beautiful. And I think Christian Robinson took my little poem and made it bigger and better with his incredible pictures. But is Last Stop the best thing I’ve ever written? Hmmm. I still think this failed novel I worked on for two years called Slightly Out of Tune is my best work.

In addition to the Newbery, you have received numerous awards and honors. Is there one that has meant the most to you? And do you feel like you’ve finally made it? Do you ever experience self-doubt or fear of future/failure?

The Newbery was overwhelming. Obviously. But seeing one of my books in a bookstore for the first time is something I will never forget. I wasn’t supposed to pull this off. I still don’t quite understand how they let me into the room. The tough thing about writing is that you feel like a failure 99% of the time. You can never ever live up to the story you aspire to write.

A Timeline of Success

2005: Ball Don’t Lie, was published by Delacorte. The book was named as an ALA-YALSA Best Book for Young Adults and an ALA-YALSA Quick Pick for Reluctant Readers.

2005: Ball Don’t Lie, was published by Delacorte. The book was named as an ALA-YALSA Best Book for Young Adults and an ALA-YALSA Quick Pick for Reluctant Readers.

2008: Mexican WhiteBoy was released by Delacorte and the short story “Last Red Light Before We’re There” appeared in the anthology Does This Book Make Me Look Fat. Mexican WhiteBoy was an ALA-YALSA Best Books for Young Adults (Top Ten Pick), a 2009 Notable Book for a Global Society, a Junior Library Guild Selection, and it made the 2008 Bulletin for the Center of Children’s Literature Blue Ribbon List.

2008: Mexican WhiteBoy was released by Delacorte and the short story “Last Red Light Before We’re There” appeared in the anthology Does This Book Make Me Look Fat. Mexican WhiteBoy was an ALA-YALSA Best Books for Young Adults (Top Ten Pick), a 2009 Notable Book for a Global Society, a Junior Library Guild Selection, and it made the 2008 Bulletin for the Center of Children’s Literature Blue Ribbon List.

2009: We Were Here was released by Delacorte. It was an ALA-YALSA Best Book for Young Adults, an ALA-YALSA Quick Pick for Reluctant Readers, a Junior Library Guild Selection, and was named to the 2010 NYC Public Library Stuff for the Teen Age list. Additionally, Ball Don’t Lie was made into a major motion picture starring Ludacris, Nick Cannon, Emelie de Ravin, Grayson Boucher, and Rosanna Arquette (Night and Day Pictures).

2009: We Were Here was released by Delacorte. It was an ALA-YALSA Best Book for Young Adults, an ALA-YALSA Quick Pick for Reluctant Readers, a Junior Library Guild Selection, and was named to the 2010 NYC Public Library Stuff for the Teen Age list. Additionally, Ball Don’t Lie was made into a major motion picture starring Ludacris, Nick Cannon, Emelie de Ravin, Grayson Boucher, and Rosanna Arquette (Night and Day Pictures).

2010: I Will Save You was released by Delacorte. It was named an ALA-YALSA Quick Pick for Reluctant Readers, a Junior Library Guild Selection, and a finalist for the 2011 Amelia Elizabeth Walden Award.

2010: I Will Save You was released by Delacorte. It was named an ALA-YALSA Quick Pick for Reluctant Readers, a Junior Library Guild Selection, and a finalist for the 2011 Amelia Elizabeth Walden Award.

2011: A Nation’s Hope: The Story of Boxing Legend Joe Louis (Illustrated by Kadir Nelson) was released by Dial Press and “Believing in Brooklyn” appeared in Guys Read: Thriller edited by Jon Scieszka.

2011: A Nation’s Hope: The Story of Boxing Legend Joe Louis (Illustrated by Kadir Nelson) was released by Dial Press and “Believing in Brooklyn” appeared in Guys Read: Thriller edited by Jon Scieszka.

2013: The Living was released by Delacorte. Matt de la Peña also wrote two books in Scholastic’s popular Infinity Ring Series: Curse of the Ancients and Eternity.

2013: The Living was released by Delacorte. Matt de la Peña also wrote two books in Scholastic’s popular Infinity Ring Series: Curse of the Ancients and Eternity.

2015: Last Stop on Market Street was released by Penguin and The Hunted (a sequel to The Living) was released by Delacorte. Last Stop received the 2016 Newbery Medal.