Prestigious authors, illustrators, and art directors regularly work together to create award-winning books. However, it is rare to find all of those in one family. Meet Art Spiegelman and Françoise Mouly—a power couple in publishing that has transformed the world of graphic novels and created an award-winning micro-publishing imprint. Spiegelman is the author/illustrator of the Pulitzer Prize-winner, Maus, and Mouly is the art editor at The New Yorker in addition to being the publisher and editorial director of TOON Books. Here, they and their daughter Nadja, share, family style, with Mackin’s Amy Meythaler how it all began and where their collaborative efforts are leading.

Nadja, Art, Dash, and Françoise

Françoise in her New York City office

Françoise alongside her New Yorker magazine covers

In The Beginning

Art and Françoise, do you remember your first reading experiences? How did you become enamored with reading—especially reading graphic novels? When it came to raising your own family, how did you encourage a variety of reading interests and literacy skills in your own children?

Art Spiegelman (AS): Funny, we all learned to read from comic books–Françoise in France, me as a kid trying to figure out if Batman was a good guy or a bad guy. He seemed so threatening when I was very young, but I figured if I could just discover what’s in those little clouds above his head, I’d find out whether he was going to hurt me or not, you know? But for me, the comics that really moved me were the humor comics, most specifically MAD and also, oddly enough, the most adult comics I got to read were Donald Duck and Little Lulu, and some of the other humor books. They had much more complex characters than the superheroes had. I loved those things.

So when we had kids, I read them both Donald Duck comics and whatever other comics seemed to be interesting to them. I remember my son going through a long jag of Krazy Kat, not believing he was really interested, but finding out that his tastes were pretty sophisticated. He genuinely dug it and asked for it again and again.

Do you remember anything I read you, Nadja?

Nadja Spiegelman (NS): You read me Donald Duck. You read me Little Lulu. You read me a lot of things. You definitely read me comics.

AS: Certainly Donald Duck and Little Lulu were favorites, and ultimately I had to sacrifice those, some of them rather valuable. At the time the kids were growing up, they weren’t really being reprinted; so I just had to let these comics sort of lose pages and have bath water that they got dunked into and whatever, but those were really great comics.

“The way to get children to fall in love with reading is to give them books they can fall in love with.” — Françoise Mouly

Nadja, what were your own first reading experiences like?

NS: I remember very vividly the feeling of lying on my father’s or on my mother’s chest at night as they were reading to me and the movement of their arms as their fingers pointed across the pages to different word balloons. It seemed totally normal to me, that this was the way that you learned to read…to have this simultaneously visual-audio experience.

Françoise Mouly (FM): Do you remember the first thing you read on your own?

NS: No, I remember that the early readers that I had to read in school were desperately boring compared to the things that I was reading at home or was being read at home. When I was able to read on my own, all I really wanted to read were books about totally normal children who had magical powers who lived in completely realistic worlds but suddenly discovered that they were magical.

AS: Well, you loved the E. Nesbit books. I think I started by reading those to you.

NS: I loved those. I also loved Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland (Macmillan, 1865) in general; I loved the story. I had, I think, four different cinematic interpretations of it, including the Disney film, but also a made-for-TV BBC drama version that was with real actors and very scary. And I had several different versions of the book, as well. My favorite was the Illustrated Alice where every spread had a depiction of the world by a different artist. Sometimes Alice was a child, sometimes she was a teenager, sometimes she was a blonde, sometimes she was a brunette, sometimes she was beautiful, sometimes she was grotesque — I loved how many different versions of the same story there could be. That had its own magic for me. There was one wonderland, but all the different versions of it allowed you to enter into all these different people’s imaginations.

Later when I was working for my mother at TOON Books, it was a similar kind of thrill to be able to come up with a story and write it, and then see that world rendered real by an artist. It was so exciting to see my world become inhabited by somebody else’s imagination.

With two very artistically gifted and free-thinking parents, I’m sure growing up in the Mouly-Spiegelman home was a unique experience. What do you remember, Nadja?

With two very artistically gifted and free-thinking parents, I’m sure growing up in the Mouly-Spiegelman home was a unique experience. What do you remember, Nadja?

NS: When we were growing up, my brother and I, we weren’t allowed to watch television. I think my parents’ idea was that the advertisements were going to wreck our brains. But, in exchange, we were allowed to read everything and anything we wanted. When my friends at school would talk about what they saw on Nickelodeon, I had no idea what they were talking about but I wasn’t teased about it. Because what everybody wanted was to come over to my house and read my comic books.

Blazing A New Trail

Clearly, graphic novels were very important in your household. Is that what led into publishing them?

AS: When the friends of our kids would come over to our house for sleepovers or whatever, they would find themselves diving through the piles of comics—something they weren’t really exposed to in their houses. So, years later, it seemed to Françoise and I, what we really owed other parents, and certainly the kids, was access to some of the best of these things.

AS: When the friends of our kids would come over to our house for sleepovers or whatever, they would find themselves diving through the piles of comics—something they weren’t really exposed to in their houses. So, years later, it seemed to Françoise and I, what we really owed other parents, and certainly the kids, was access to some of the best of these things.

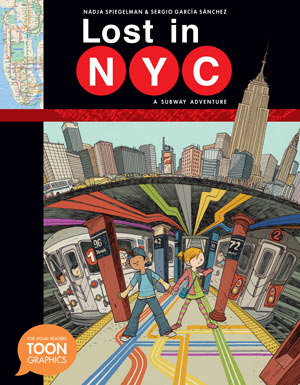

It turned into a project called the TOON Treasury of Classic Comics (Harry N. Abrams, 2009). It was a very complex…project of editing. I pulled together a board of peers, people who are real experts in old comic books—historians, critics, writers–people not only figuring which artists and writers should be included in a best of old comics from the ’30s to the ’50s collection, but which stories, which led to very heated and interesting exchanges.

The TOON Treasury of Classic Comics was a very solidly built book, and it didn’t take the easy route out. For example, the Disney Corporation is a very difficult corporation to yank a copyright out of, and miraculously, even that was able to be arranged. We had intended this to be the equivalent of a Betty Crocker cookbook—no home should be without one—a book to be passed from generation to generation. I don’t know that it ever reached that acme of placement, but nevertheless we did provide a book that is a one-volume genuine treasure and a treasury.

But even before your TOON Treasury was made available, you had reinvented and reintroduced comics as a legitimate story-telling medium with RAW. Prior to that, comics were primarily viewed as silly reading material for children, right?

FM: When we started RAW, a magazine of comics and graphics in 1980, it was to fill a gap, to show all the great work that could be done in comics. No one else was publishing comics in the U.S., neither in magazines nor in books. Bringing European, Japanese, and American artists together in RAW had a great impact, which was compounded by the publication of Maus I (Pantheon, 1986) and Maus II (Pantheon, 1992).

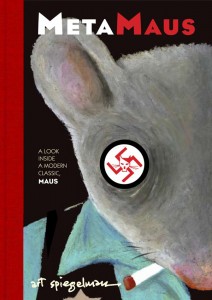

Maus certainly did make a great impact! It singlehandedly altered the opinions of many about the role of graphic novels as “real” reading material. And, it was the first graphic novel to ever win a Pulitzer Prize. Do you view this story as your pinnacle piece of work?

AS: I just wasn’t prepared for the overwhelming positive response to Maus. I’d been doing comics that required people to slow down and study rather than read. I’d arrogantly assumed my work would be appreciated posthumously. The success of Maus called my bluff. I had actually thrived on the relative neglect; it made me get up and work. Ironically, the anhedonic way I experienced the success of Maus was to spend the next twenty years trying to wriggle out from under my own achievement.

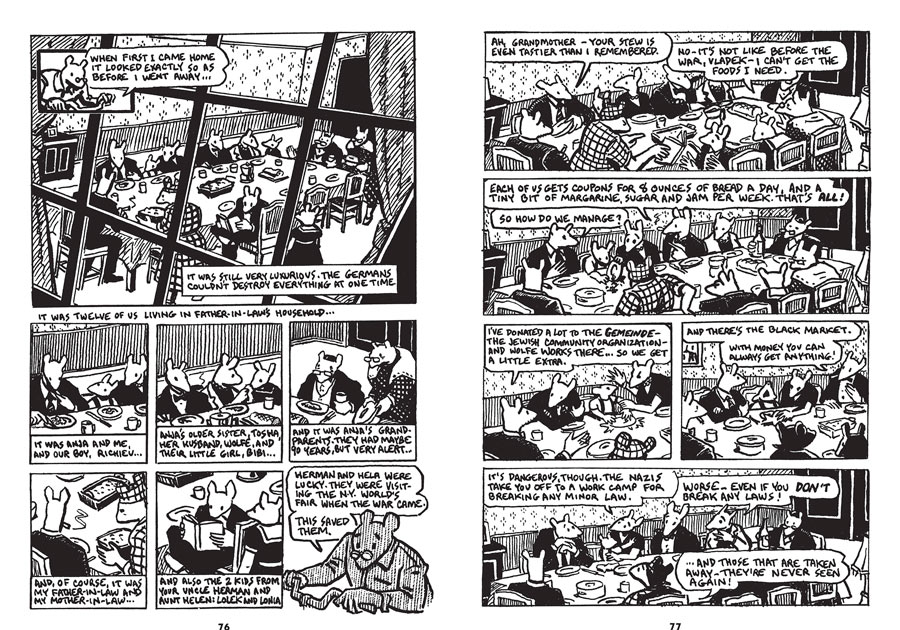

Spread from The Complete Maus. Artwork by Art Spiegelman.

Spread from The Complete Maus. Artwork by Art Spiegelman.

Initially, my idea was just making a three-page comic strip. I didn’t have the stamina to devote myself to a one-hundred, two-hundred, three-hundred-page book just to serve up a lot of yuks or escapist melodrama. After the three-page “Maus,” I realized I had unfinished business, something to go back to.

The story of Maus isn’t just the story of a son having problems with his father, and it’s not just the story of what a father lived through. It’s about a cartoonist trying to envision what his father went through. It’s about choices being made, of finding what one can tell, and what one can reveal, and what one can reveal beyond what one knows one is revealing. Those are the things that give real tensile strength to the work.

So what came after RAW and Maus?

FM: I launched a RAW Junior division in 1998 to fill what I experienced as a gap. With RAW and with Maus, we had shown that comics could tackle serious topics—that they were not just for kids anymore. But now that we were parents, I wanted artists to be similarly inspired to do work for children. Great artists should not just undertake 300-page graphic novels about serious topics. Why wouldn’t they apply their skill and do short stories or humorous one-pagers for children? There just weren’t enough good children’s comics being done in the U.S. at that time.

Acting On Instinct

How did you know that there would be a big enough market for children’s comics?

FM: I’m very lucky; all my life I have been able to follow my instincts, and act on impulses born when I fell in love. I loved being a mother and I loved reading books and comics with our daughter and our son.

We sacrificed our collection of Carl Barks’ Donald Duck and Little Lulu to parenthood. Since I only spoke French with the kids, I brought back suitcases of French comics at every trip. But it’s when the school insisted that we make our kids spend their reading time with “early readers” that I really felt the crying need for better material. I could see how a simplified vocabulary and step-by-step approaches were useful, but I was appalled by the lack of quality and appeal in the books that were assigned.

The kids were turning away from story time whenever I tried to bring out those primers, and I couldn’t blame them. Meanwhile, they were begging for more comics, and it was obvious why they were so attracted to the medium: the visual narrative held their attention; they could see the emotions on the characters’ faces [and] decipher the sound effects; the page layouts often diagrammed out the pace of the story. All their friends who came to the house spent hours reading all the comics that were lying around.

The kids showed me the way: It was obvious that the way to get children to fall in love with reading is to give them books they can fall in love with. Children are no fools—as a matter of fact, they’re efficiency experts: they’ll invest, work toward something only if they gain a benefit from it. The first books we put in their hands have to deliver good stories, art, humor. The books have to be memorable, worth re-reading. They have to thrill their readers, make them laugh and cry, let them learn something new.

So where did you start and were your efforts met with success? Was the market ready for what you had to offer?

FM: When I founded a RAW Junior division in 1998, I wanted to address what I thought was the most crying need and launch the TOON Books, but Art was wary of the limited vocabulary and step-by-step approach and we had to start somewhere. So as with RAW, our first impulse was to work with the best artists in the field and publish material that would speak for itself.

Little Lit (Harper Collins, 2000-2003) were hardcover anthologies of short stories in comics form on themes like fairy tales by the likes of Maurice Sendak, Gahan Wilson, William Joyce, Barbara McClintock, Ian Falconer, Chris Ware, Dan Clowes, David Mazzucchelli, Daniel Handler, Neil Gaiman, Paul Auster, and David Sedaris—an all-star cast of writers, artists, and cartoonists.

“Each TOON Book has been vetted by educators to ensure that the language and the narratives will nurture young minds.” — Françoise Mouly

We were working with a wonderful editor, Joanna Cotler, at HarperCollins. We thought every library would grab them—that they would be the cornerstone of a children’s comics section in stores and libraries and that HarperCollins would want to expand with individual books. But they didn’t.

We ended up doing a Big Fat Little Lit (Puffin, 2006) compilation with Penguin. It probably was too early for its time since the Chris Duffy anthologies, which are built on a similar formula but came ten years later, have done well.

I knew the concept of the TOON Books—leveled readers in comic format—was sound but that publishing-wise, it was far from obvious since it fell outside of traditional children’s books and was also outside the new category of “graphic novels.” I pitched the concept, the line of books to every publisher for years—from 2003 to 2007—only to encounter an endless series of amiable rejections. It was a great idea I was told, beautifully executed (I had already made dummies of three or four books), but no one was ready to launch a new category at a time when the future of publishing felt so precarious.

How did you handle the rejection?

FM: So in the summer of 2007, I decided to go back to my roots as a self-publisher and we launched TOON Books in the spring of 2008, just in time for the economic collapse. In retrospect, it’s lucky no publishing house took it on; otherwise, we would have been the first casualty out of the door before we even had a chance.

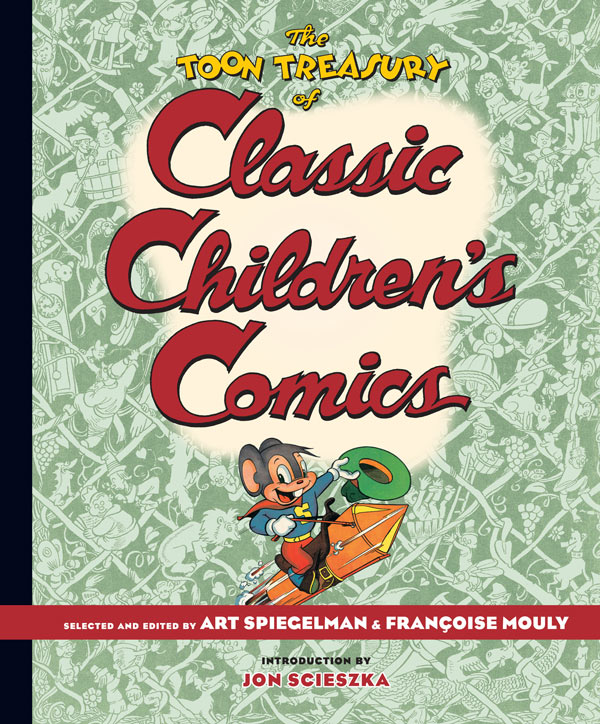

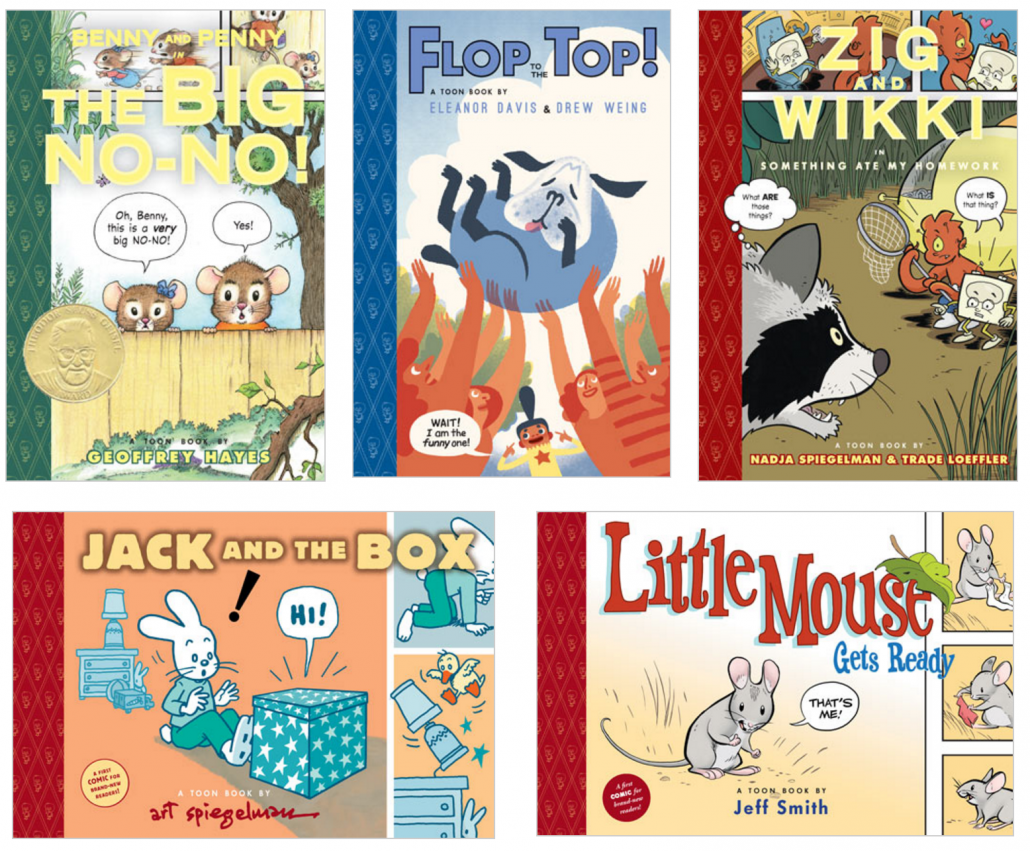

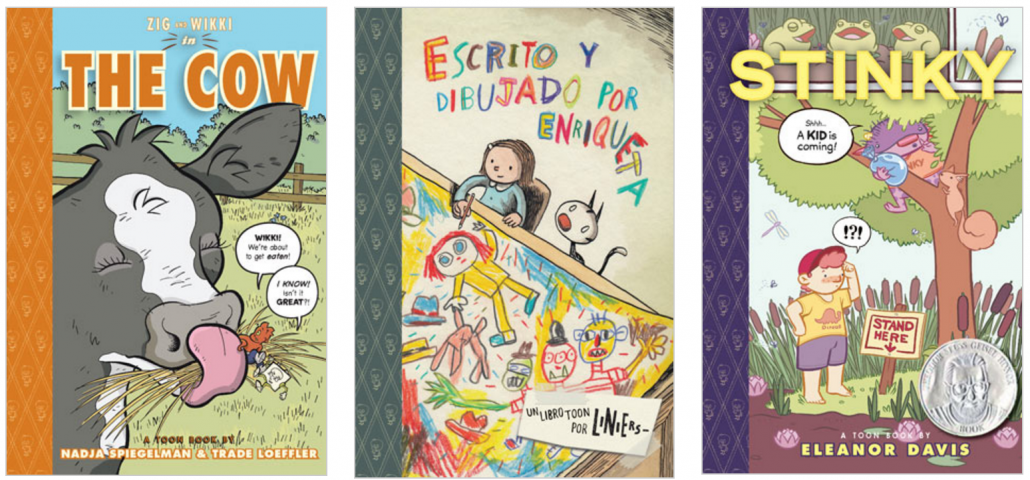

As it is now, working as an independent micro-publisher, we have over 30 TOON Books across the beginning reading levels. And, we just launched TOON Graphics which are comics for the ages 8-12 set.

Entering The World Of Education

So what makes your publishing company and your collection of graphic novel titles different from what is already available? Why are TOON Books an important addition to a family, classroom, or school library?

FM: As many teachers, librarians, booksellers, and parents will attest, children LOVE comics! This is the first collection ever designed to offer early readers comics they can read themselves. Visual narrative helps kids crack the code that allows literacy to flourish, teaching them how to read from left to right, from top to bottom. Speech balloons facilitate a child’s understanding of written dialogue as a transcription of spoken language. Many of the issues that emerging readers have traditionally struggled with are instantly clarified by comics’ simple and inviting format.

As a matter of fact, the TOON Books have been eagerly adopted by teachers and librarians and are widely used in the classrooms of Maryland, New York, Florida, and many other states. Each TOON book has been vetted by educators to ensure that the language and the narratives will nurture young minds. Our books feature original stories and characters created by veteran children’s book authors, renowned cartoonists, and new talents, all applying their extraordinary skills to fascinate young children with tales that will welcome them to the magic of reading.

We have also developed the TOON into Comics Genre Study which includes 30 Common Core State Standards (CCSS)—aligned lessons plus supplemental materials for every TOON Book. These lessons integrate research-based best practices for close reading, text analysis, writing to text, narrative and expository writing, and fluency development. The unit emphasizes the development of students’ visual as well as verbal literacy, and culminates with a publishing party at which students present their self-authored comic books.

I’ve heard that TOON Books believes so strongly in the importance of graphic novels in the classroom that the company has embarked on philanthropic donations.

FM:Yes, it is true. Over the last two years, TOON Books has made donations totaling $50,000 that have enabled teachers to get the TOON into Comics Genre Study at half off. We have worked through DonorsChoose.org, and MackinVIA did a special promotion in February 2014 that utilized the entire collection as eBooks and included the genre study guide. We estimate we are in more than 300 schools now with the genre study program.

Reading The Future

So what comes next for TOON Books? What can educators, parents, kids, and fans in general look forward to seeing soon?

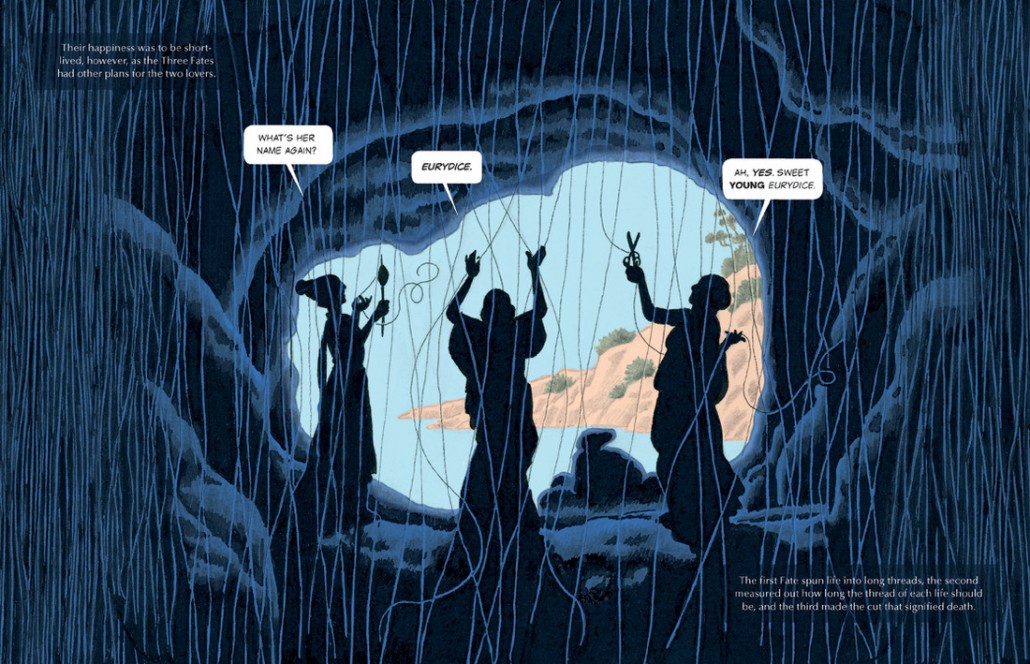

FM: This fall and into the next years, TOON will publish a whole array of TOON Books and TOON Graphics. We’re building the Graphic Greek Mythology series by Yvan Pommaux and the Philemon series by Fred. We’re publishing new books by some of our bestselling artists and some first books by new, innovative creators. Our list keeps widening in diversity and reach: We now have TOON Books or TOON Graphics for every reader at every stage from infancy to adulthood. (The new Little Nemo: Big New Dreams [TOON Graphics, 2015] is an all-ages collection.)

What’s making my dream come true—where there’s a real momentum of change—is the growing acceptance of our collections in schools and libraries. Our books are now routinely integrated in the curriculum for K-3 (for the TOON Books) and for grades 4-6 onto high school (for the TOON Graphics).

The former resistance and distrust of comics is turning into a broad embrace of the medium by kids with the support of educators and librarians. We now hear from parents who have discovered the pleasure of reading comics from their kids—who themselves got hooked in school or at the library. It’s the world upside down but, in this time of digital overload, it feels that reading and reading comics is here to stay—something that makes me very happy.

How To Read Comics With Kids

“Comics are a gateway drug to literacy.”— Art Spiegelman

Kids LOVE comics. The details in the pictures make them want to read the words. Comics beg for repeated readings and let both emerging and reluctant readers enjoy stories with a rich vocabulary. TOON Books, the first high-quality comics designed for children ages four and up, are vetted by educators and leveled to be just right for beginning readers. Pick up a Level One, Level Two, or Level Three book today. Here are the top ten tips for reading comics with kids…

1. Find The Right Book

There are many comics and graphic novels out there, but not all are appropriate for every age. Look for titles made especially for children. It’s best to choose a story that fits the child’s age and interests.

TIP: The TOON Books collection is designed for the beginning or early reader.

2. Guide Young Readers

Keep your fingertip below the character that is speaking, so kids can follow along with the story even if they can’t yet read the words.

3. Ham It Up!

Think of the comic book story as a play. Don’t hesitate to be a ham! Read with expression and intonation. Assign parts or get kids to supply the sound effects—it’s a great way to reinforce phonics skills.

TIP: Even very young readers will enjoy making the easy-to-read sound effects.

4.Let Them Guess

Comics provide lots of context for the words, so beginning readers can make informed guesses. In Benny and Penny in Just Pretend, for example, Geoffrey Hayes introduces the word “PIRATE” along with a pirate ship, two pirate hats, and two pirate flags.

TIP: The child who makes informed guesses is reading. Enjoy and hold back from correcting.

5. Talk About The Picutures

A comics artist communicates information through the shape of the panels (and can make you laugh by putting panels upside-down.) Point out how the artist directs the reader’s eye, because readers look at what the characters look at. The composition of the right-hand page below points to the bird flying away, breaking out of the panel.

TIP: Get kids talking, and you’ll be surprised at how perceptive they are about the pictures.

6. Take The Time Silent Panels

Comics use panels to mark time, and silent panels count. Look and “read” even when there are no words. Often, humor is all in the timing!

7. See How Pictures Tell The Story

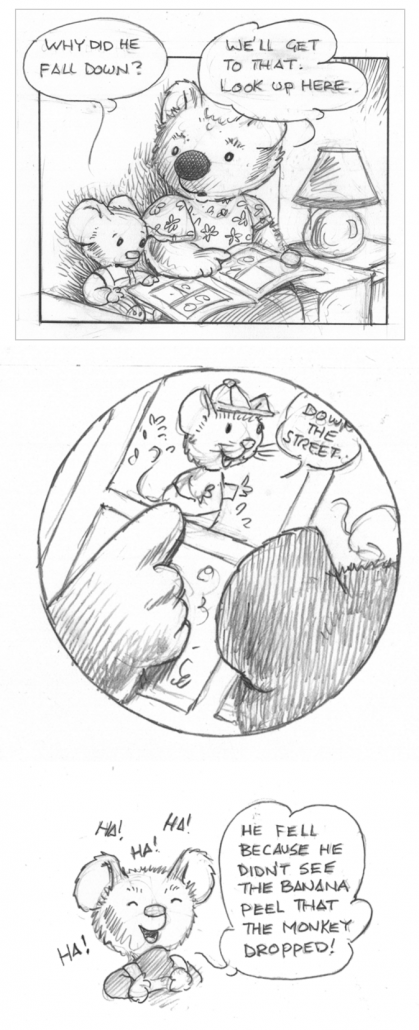

In a comic, you can read the story even if you don’t know all the world. Jeff Smith, the master cartoonist behind the BONE series and the Little Mouse Gets Ready TOON Book, is a skilled visual storyteller. Get young readers to tell you what’s happening in the sequence below based on Little Mouse’s facial expressions and body language.

TIP: Seeing the hand of the artist at work in comics makes kids want to tell their own stories. Encourage them to talk, write, and draw!

8. Get Out The Crayons!

Young readers are young writers! Activities like coloring pages and scramble comics jump-start kids’ enthusiasm for storytelling. Encourage children to create their very own stories using the Comic Makers.

TIP: When drawing your own comic, write the words first, then draw balloons around them!

9. Let Them Re-Read

Not only do children love to read comics, they also love to RE-read them. When re-reading a comic, kids find all the details that make comics so pleasurable. Beginning readers then become fluent readers.

10. Above All, Enjoy!

There is never one right way to read, so focus on sharing your fun. Once children engage with the story in their imagination, they discover the thrill of reading. At that point, just go get them more books–and more comics!

Using Toon Books In The Classroom

Comics are here to stay. Hopefully, the “here” is in your classroom. Not sure what comics can do for your students? In addition to developing critical visual literacy skills in emergent readers and engaging reluctant readers, TOON Books comics, in particular, have a lot to offer classroom teachers and their students.

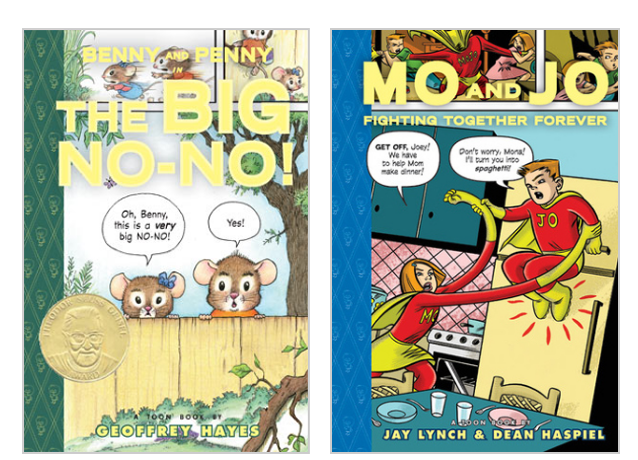

Comics make great classroom read-alouds. You can project the eBook for the class to see or distribute print copies of the book to your students to make sure that each student can get a good view of the art. From there, you can have fun with the expressive language and onomatopoeia in Benny and Penny and the Big No-No! (TOON Books, 2014) or Mo and Jo Fighting Together Forever (TOON Books, 2013).

Comics make great classroom read-alouds. You can project the eBook for the class to see or distribute print copies of the book to your students to make sure that each student can get a good view of the art. From there, you can have fun with the expressive language and onomatopoeia in Benny and Penny and the Big No-No! (TOON Books, 2014) or Mo and Jo Fighting Together Forever (TOON Books, 2013).

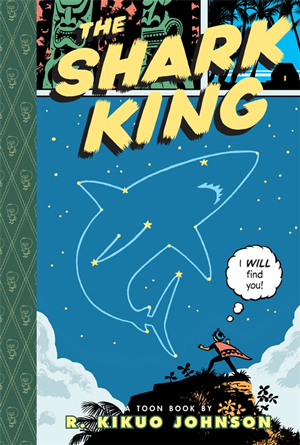

Comics connect to art and culture. The Shark King (TOON Books, 2013) by R. Kikuo Johnson is a retelling of a Hawaiian legend for beginning readers. The beauty of the island is richly depicted in the art, and the story offers young readers a glimpse of a culture with which they may not be familiar.

Comics reinforce language arts lessons about dialog, descriptive language, and storytelling. Otto’s Orange Day (TOON Books, 2013) is a great choice for a unit on adjectives, and Little Mouse Gets Ready (TOON Books, 2013) introduces sequence words.

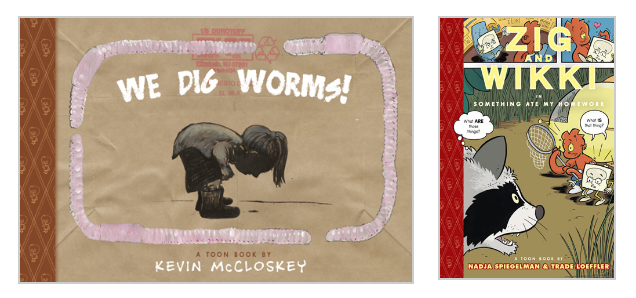

Comics offer a fun take on science concepts. We Dig Worms(TOON Books, 2015) is full of facts about worms that is as informative as it is entertaining. Zig and Wikki’s adventures introduce young readers to the food chain, animal adaptations, and digestion while grossing them out at the same time.

These are just a few of the possibilities for using comics in your classroom. In addition to these ideas, many TOON Books provide an opportunity for reader’s theater and visual literacy activities. You might have your students use the CarTOON Maker from toon-books.com to give them a chance to create their own stories or use the activities in the Just for Kids section of toon-books.com to jumpstart a creative writing or drawing exercise. And be sure to check out toon-books.com for lesson plans and other tools for educators.

— Mindy Rhiger, MLS, Mackin Collection Management Department

Toon Greek Mythologiest

When Dash was young, a friend had usefully recommended that we get the audio version of the d’Aulaire’s book of Greek Mythology. We listened to the stories every morning in the car pool—it kept the 5 young boys and me mesmerized for years. Those stories are truly iconic—I’m grateful to now have a chance to publish a Graphic version, making them accessible to new generations of kids growing up in the 21st century.

— Françoise Mouly

Interior spread from Orpheus in the Underworld