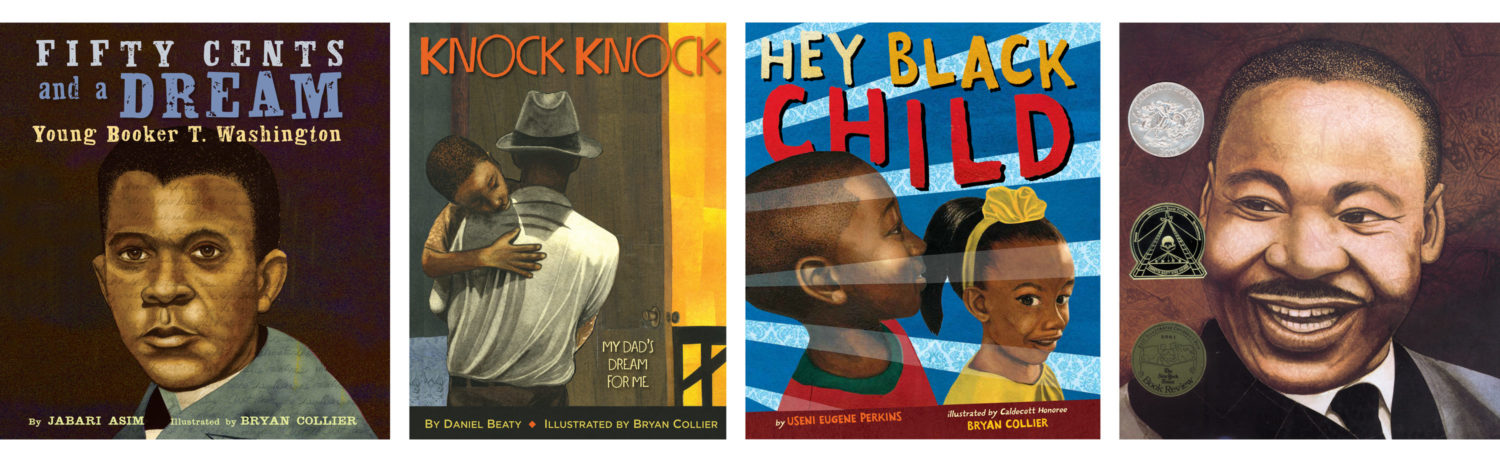

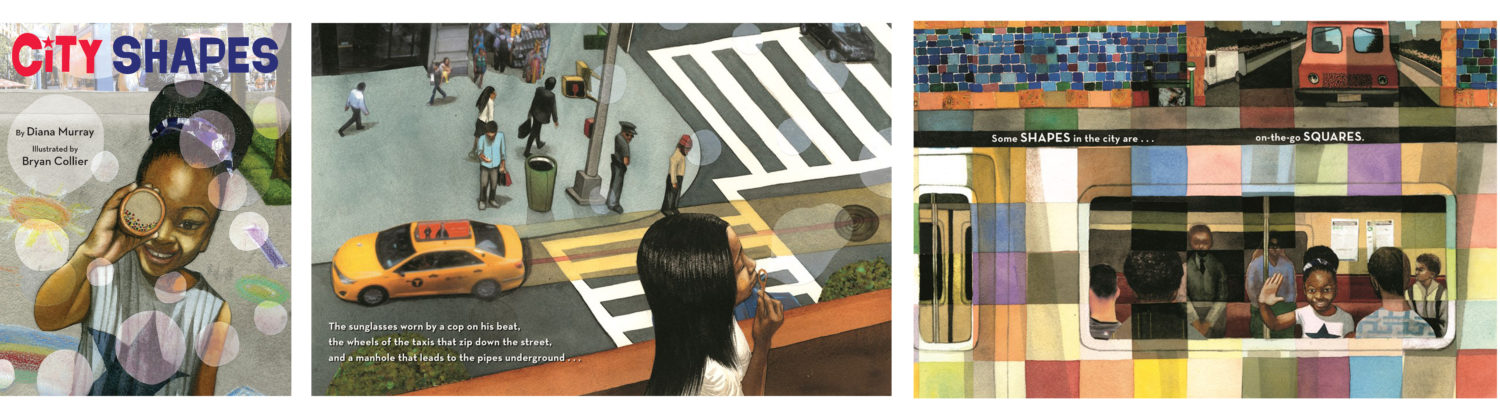

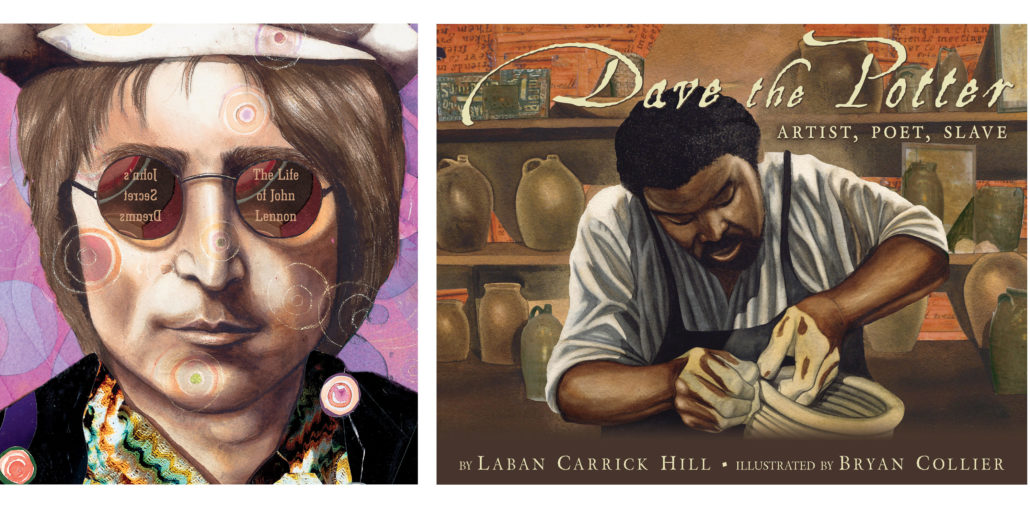

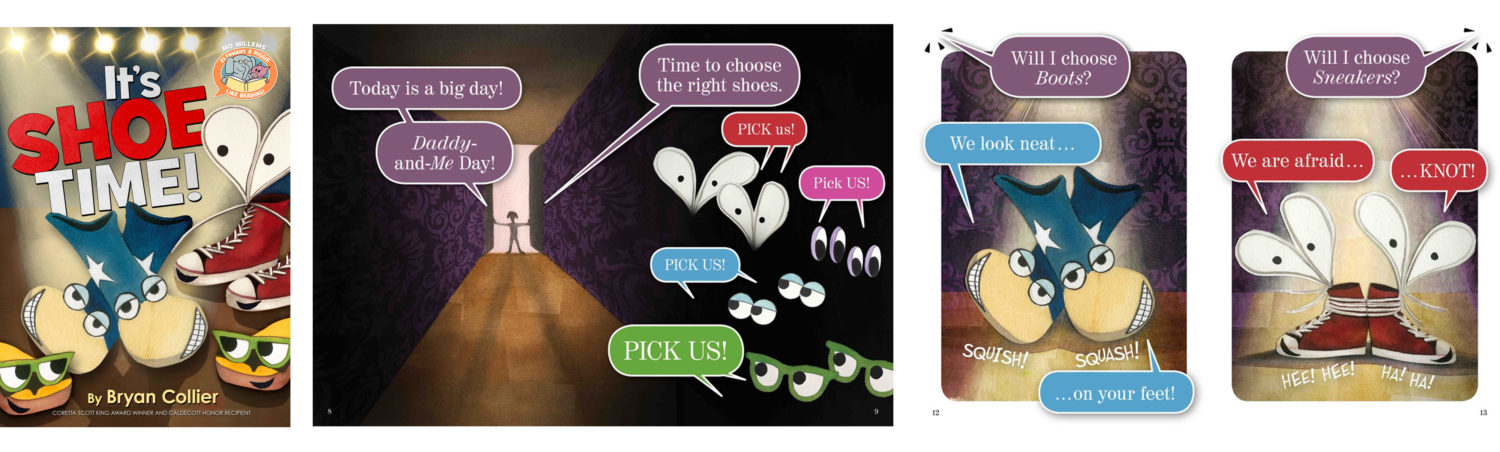

Artist Bryan Collier’s work speaks to thousands of readers with its signature combination of collage and watercolor that automatically pulls them into the illustrations. Full of textures and rich color, Collier’s illustrations have also caught the eye of award committees that recognize their beauty and impact. He has received multiple Caldecott Honors and several Coretta Scott King Awards, and was selected as the U.S. nomination for the 2014 Hans Christian Andersen Award. Here he shares his thoughts on his work, the state of art and publishing, and the future.

With a mother who was a Head Start teacher, I’m sure you must have had access to plenty of great books at home from a young age. Why did your parents feel having books was so important?

With a mother who was a Head Start teacher, I’m sure you must have had access to plenty of great books at home from a young age. Why did your parents feel having books was so important?

I don’t remember plenty of books, but my mother did bring home enough for six children to share. My mother was an educator and books were an automatic part of the deal.

You discovered your gift for painting when you were about 15 years old. What inspired you to even try watercolor painting? Did you have any artistic influences during your childhood?

At 15, watercolors were the only paints I had and could afford. I was totally taken by the water and pigment combination and dazzled by what color could do. I do consider myself to be self-taught, but my grandmother made quilts when I was younger (4-7 years old). After I graduated from Pratt Institute in 1989, I discovered I was unconsciously drawing on her influence with the layering, overlapping, and landscape imagery.

You have definitely developed a unique method for combining collage and watercolor. Do you feel like your skills are still evolving or have you settled into your signature style?

You have definitely developed a unique method for combining collage and watercolor. Do you feel like your skills are still evolving or have you settled into your signature style?

I think the work is still evolving. I mean, I still have so much to say with the work. The presence of different intensities of light as it falls on characters and objects is a big part of me capturing the mood and tone of the text. In terms of style, I just focus on clarity of message and let everything else take care of itself.

“The best thing and the hardest thing about making art is that everything you did yesterday doesn’t count today and it can’t help you with what you are working on today. Every day you start new, a blank surface.”

While you were a student at Pratt, you began working with Harlem Horizon Art Studio. What is the concept behind this hospital-based art center?

I started as a volunteer in the Harlem Horizon Art Studio a month before I graduated from Pratt. I was paid a stipend and I also sold my artwork at that time to support myself. The HHAS is a painting studio located on the 17th floor pediatric wing of the Harlem Hospital that gives children—those in the hospital who are there for various treatments as well as children from the Harlem community—the opportunity to make art, free of charge. The freedom of expression demonstrated by the children was and is delightful, and resonated with me.

I read that you decided to try your hand at children’s books when you didn’t see many that reflected black people and stories. Were you an instant success?

I pursued making a picture book soon after graduating from Pratt. I went door to door once a week, every week, for seven years until I got a book deal.

So how do things look to you today, 25 years later? Do you see better representation? What impact have your books Hey Black Child (Little, Brown Books for Young Readers, 2017) and Dave the Potter (Little, Brown Books for Young Readers, 2010) had on the industry?

Diversity is still a big issue in publishing. Hey Black Child and Dave the Potter have been received well in the market place and embraced by the public, but more needs to be done to include more writers and artists and editors and designers of color.

Your work has been very well received from readers, teachers and librarians, and awards committees. To what do you attribute your success?

I think everyone recognizes the honesty, love, and commitment I put in the work. And I absolutely love teachers and librarians! I love when teachers and librarians use my books to bring the text alive.

Unfortunately, more and more schools have found art budgets slashed with decreases in school funding. How do you feel about the scarcity of artistic resources and instruction in education?

Art is always the first to get cut yet it is so vital to our survival. We have to keep fighting for the arts.

As an artist and author, you have received some incredible honors. For example, your book Trombone Shorty (Harry N. Abrams, 2015) was named a Caldecott Honor Book and you also received yet another Coretta Scott King Award. What is your view on awards?

I think awards are great and can put a great spotlight on your work which in turn allows you to reach more people, and that is a good thing.

One of these days, when you set aside your paints and collage supplies, what do you hope your legacy will be? How do you want to be remembered?

One of these days, when you set aside your paints and collage supplies, what do you hope your legacy will be? How do you want to be remembered?

I want to be remembered as someone who simply dream walked in the fullness of the day with his heart and eyes wide open.