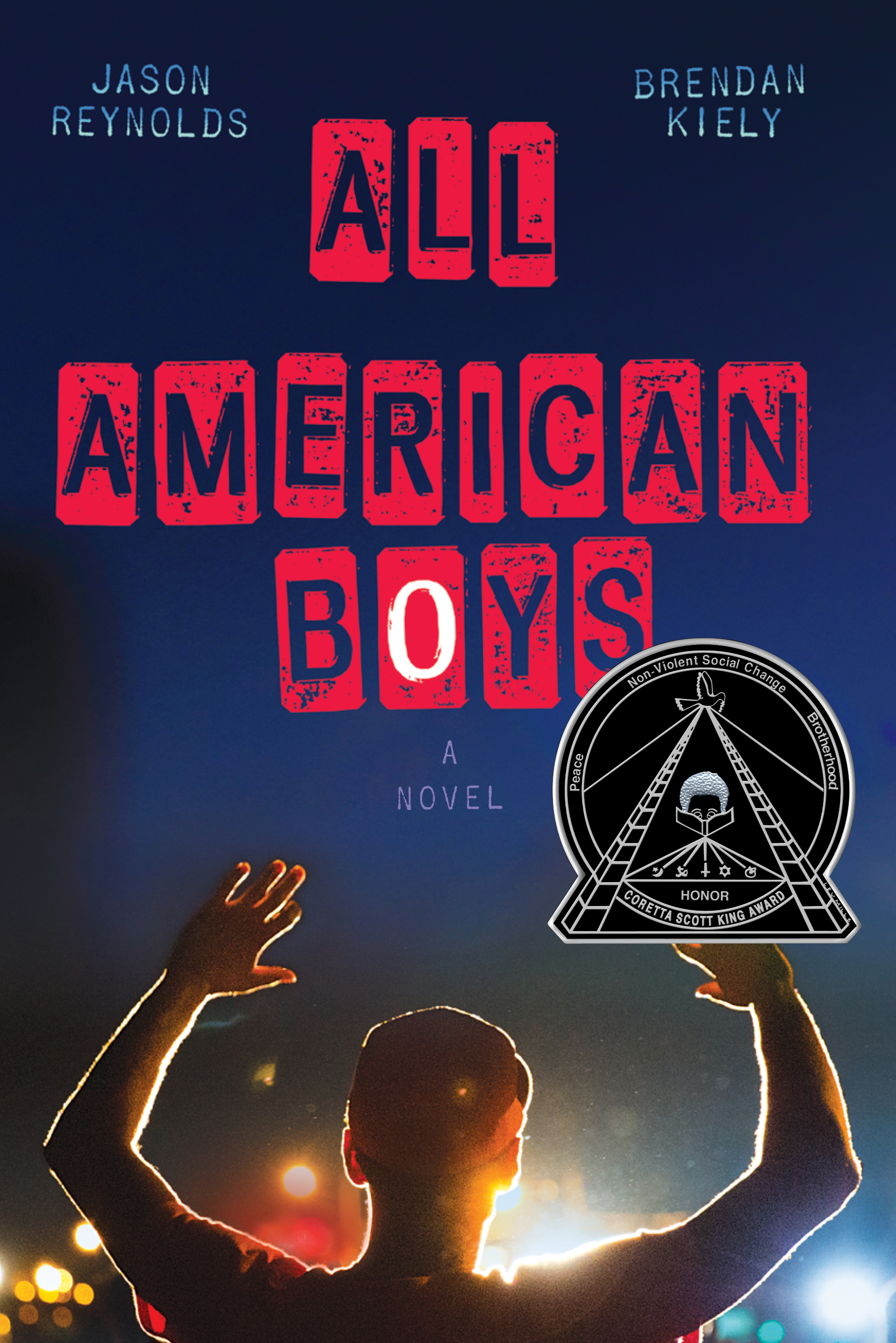

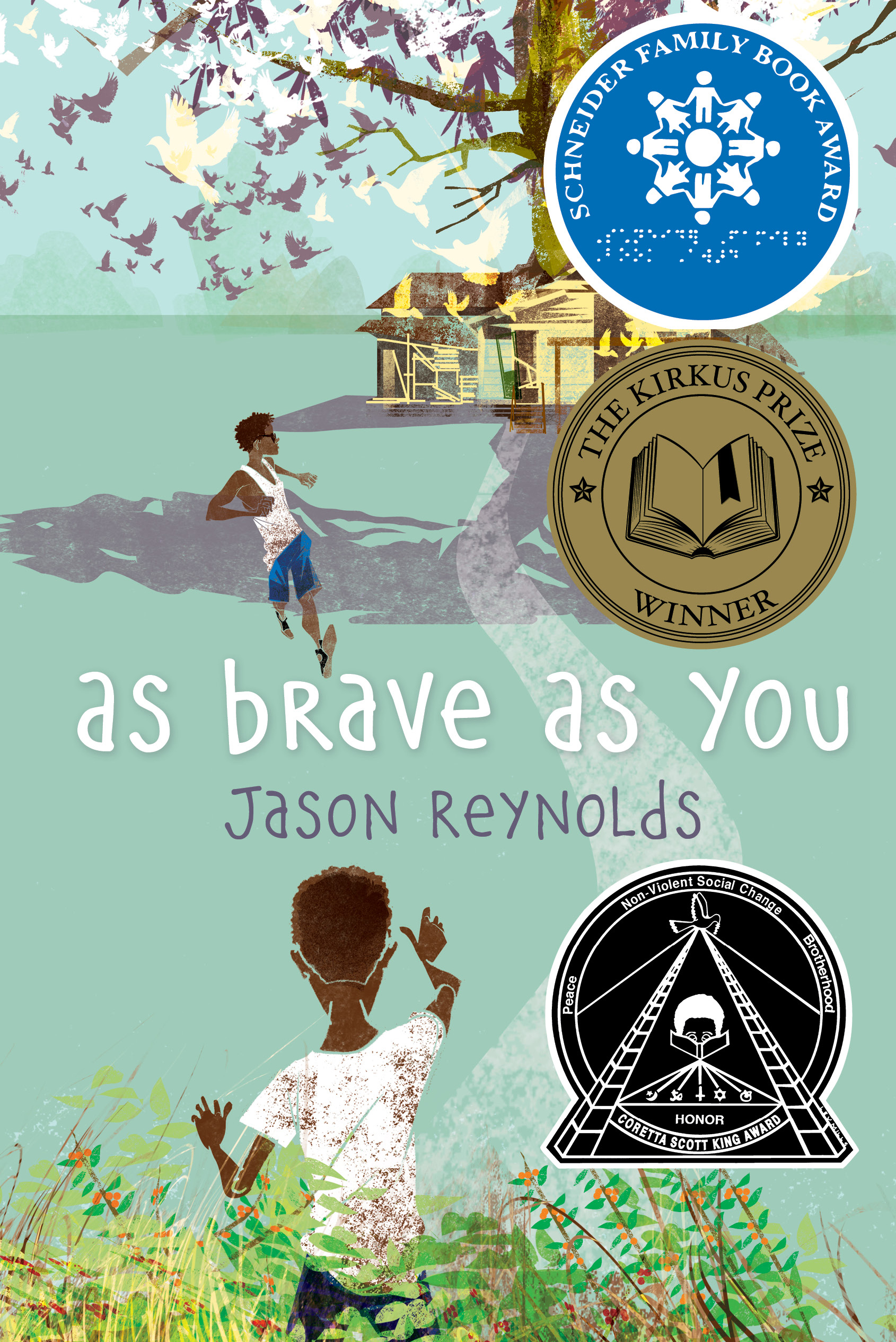

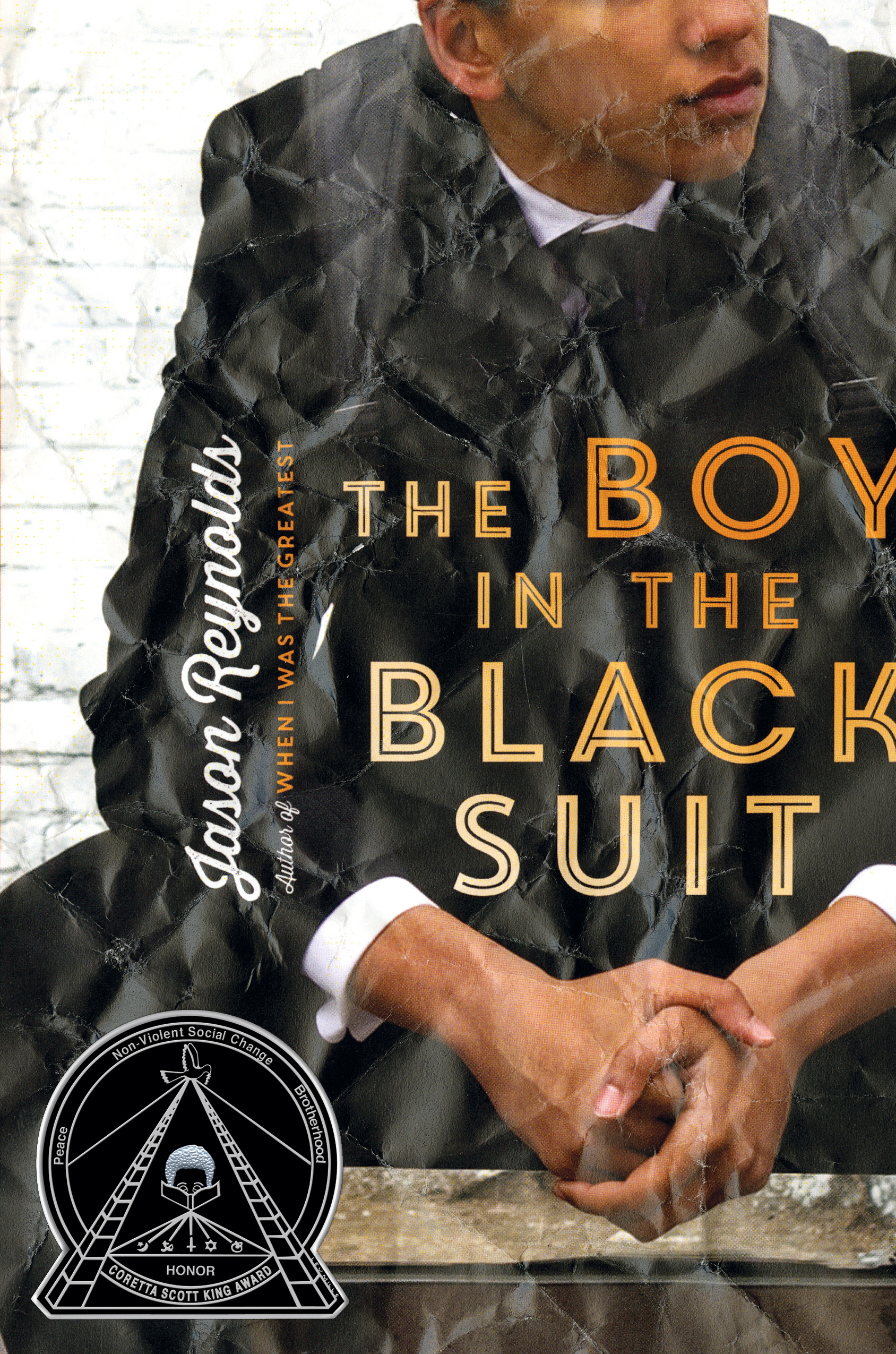

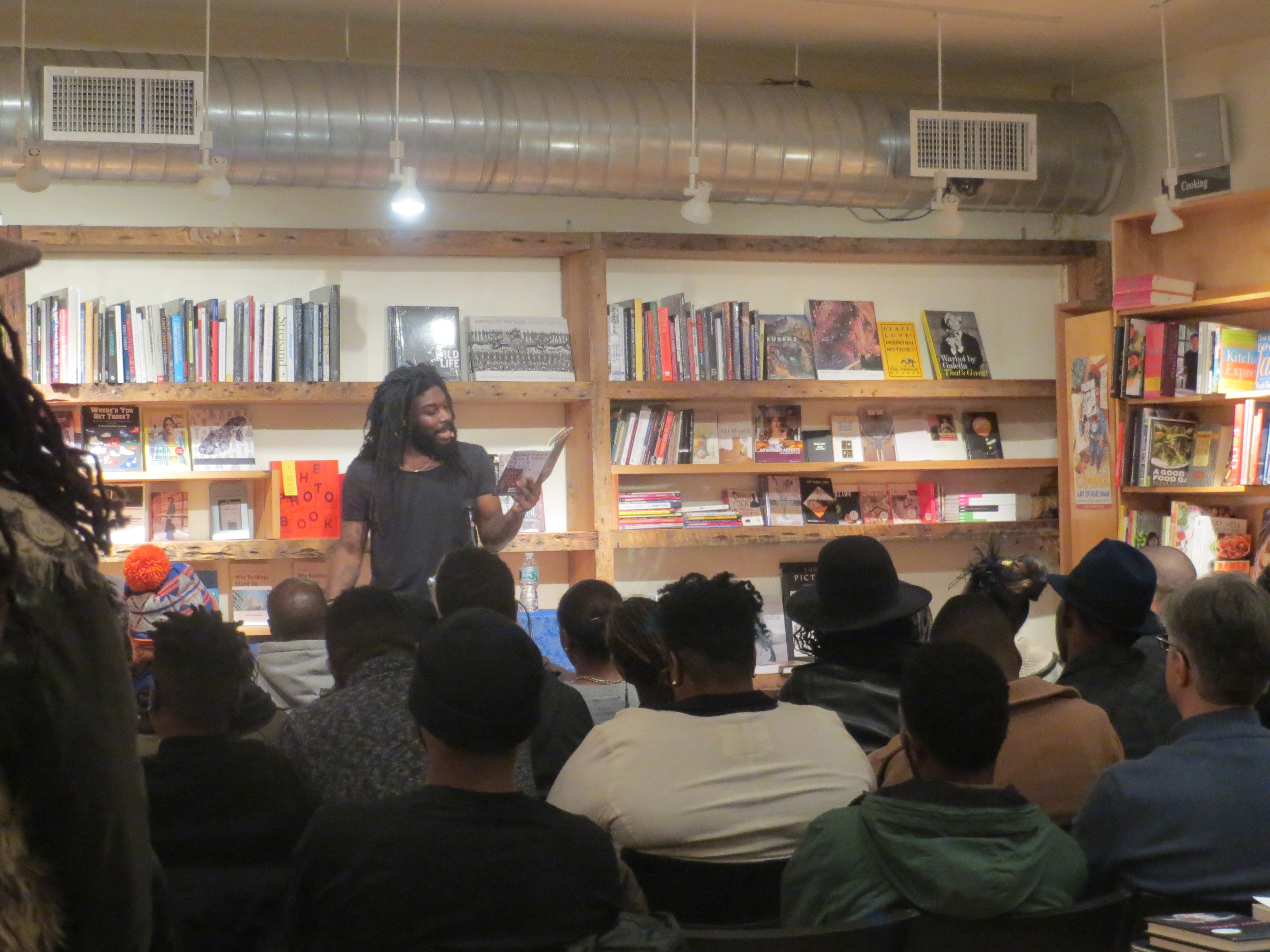

Jason Reynolds has been deemed one of the most promising young adult novelists today. He has received prestigious accolades and awards including several Coretta Scott King Awards and Honors, the Kirkus Award, being named a National Book Award finalist, and becoming a New York Times bestselling author. Additionally, he is on the faculty at Lesley University for the Writing for Young People MFA program. Yet, he was not always interested in books. Here Mackin’s Amy Meythaler asks Reynolds to share insights into his background and how he discovered his love for poetry and prose.

Where did you grow up and what was your home life like?

I grew up just outside of Washington, D.C., with mainly my mother and older brother, though my house was the house everyone lived in at one point or another. Aunts, cousins, my father. Always people there.

Were books, libraries, reading, and writing important in your family?

Were books, libraries, reading, and writing important in your family?

It’s weird to look back on it all now, only because books were everywhere in our house, though I don’t recall seeing anyone actually reading. They were there, though. And the collection of books—at least my collection—was growing. Every year for Christmas my aunt would give me a classic. And every year I tossed it aside. I mean, seriously, who wants books for Christmas? Especially the classics?!

Apparently you gave up reading books when you were quite young. What happened?

“I wish teachers back then let us read anything. I wish they understood that my life, my personhood, would be strengthened by literacy, not just literature. So had I been allowed to read rap lyrics in school, or video game cheat code books, or whatever I was interested in, I would’ve been better off.”

The entire medium was something I was uninterested in. Well, I take that back. It wasn’t that I was uninterested as much as it was that I felt disconnected from it. School, back then, discouraged whatever relationship I could have had with books by not providing me, and kids like me, with options. All I needed was something familiar. A family like mine. A neighborhood like mine. Language like mine. But it’s unfair for me to just say teachers didn’t try. Some of them, I’m sure, were working to figure out how to crack the code. But it’s hard to do when the options for the books I needed were so scarce. Today, fortunately, there are more options. There are contemporary stories, layered and authentic. There’s a creativity, an irreverence, and a growing inclusivity that makes reading more palatable. More accessible. More fun!

I wish teachers back then let us read anything. I wish they understood that my life, my personhood, would be strengthened by literacy, not just literature. So had I been allowed to read rap lyrics in school, or video game cheat code books, or whatever I was interested in, I would’ve been better off. I know being a teacher is difficult because of all the red tape and bureaucracy, so I don’t want to pretend that implementing this kind of thing is easy. But it’s worth trying.

About the same time you lost interest in books, you discovered poetry. What inspired you to take up reading and writing poetry? And how do you suggest educators help the young people they work with find an appreciation for poetry as well?

I found poetry through rap music. I think it’s MUCH easier to get kids interested in poetry if you break down the barrier between the poets in their textbooks and the poets in their ear buds, which immediately gives credence to some of the poets in the classroom. There are always kids who rap. Who sing. They’re poets. Dissect Kendrick Lamar lyrics. Dissect Tupac. Lorde. Taylor Swift. Whoever.

“School, back then, discouraged whatever relationship I could’ve had with books by not providing me, and kids like me, with options. All I needed was something familiar. A family like mine. A neighborhood like mine. Language like mine.”

I know there are some poetry snobs out there turning their noses up at this idea, and that is precisely the issue. Shakespeare was brilliant, but not because he was over people’s heads. He was brilliant because he could bring raucous stories to everyday people, and its sophistication had everything to do with his ability to connect and poke fun using metaphor and entendre. That’s rap music. That’s poetry.

The other thing about poetry, for me, was that it was short. It was punchy and immediate and far less daunting than prose. Less words on a page was enough for me to try to write it and read it.

Obtaining a degree in English seems highly unlikely for someone who gave up reading. How did your choice of a college major come about? And did your lack of a rich reading background hinder you at all?

“It’s much easier to get kids interested in poetry if you break down the barrier between the poets in their textbooks and the poets in their ear buds.”

It was a struggle. I loved to write poetry and was determined to be a successful (read: famous) poet since I was a kid. So the English degree didn’t seem that far-fetched for me. But I was completely unprepared because I hadn’t read anything. As a matter of fact, I started as an English major but changed it several times to Education, Journalism, Communications, and eventually landing back on English. But I also started reading, and, therefore, played catch up. But I never wavered from what I wanted—to be a poet. That’s it. Not a teacher. Not a lawyer. Not even a novelist. A poet.

Reynolds Reflects on the Power of Literacy and Story

“I never wavered from what I wanted—to be a poet. That’s it. Not a teacher. Not a lawyer. Not even a novelist. A poet.”

“We all need to know how to read. Our children need to know how to navigate language because with words we can bolster self-confidence and cut down on violence and almost every other interpersonal conflict. For example, when I was young and I would get upset but couldn’t find the words to express my anger, I would break things. That’s human. Had I been able to wrangle my language and articulate my feelings, I would’ve, perhaps, been able to let some of the air out before bursting. And in terms of the importance of stories…well, imagine if I had never known that I wasn’t the only kid on earth who got mad enough to break his own toys? Imagine the loneliness and insecurity that might set in. Stories are the imaginary friends that do real things. That actually throw the ball back.”

To what do you attribute your success today? Having received so many honors and awards so early in your career, do you now feel pressure to keep being successful?

You know, when it all comes down to it, I attribute my success to my intuition, my work ethic, and an incredible support system. I write from the gut. I put it on the page in a way that feels good to me, even if that means I have to break a few rules. And I’m relentless. Obsessive, even. Every book is treated like the first. And I’m super lucky to have an agent and an editor to push me and tell me it’s okay when I’m falling apart. And I do fall apart sometimes.

Do I feel pressure? Sure. But not because of the awards. I’m just always in competition with myself to make sure that everything with my name on it is as good as I could’ve possibly gotten it at the time. I put the pressure there to keep me grounded, to keep me focused. Shiny things can shatter thoughts. I have to remind myself everyday what I’m doing and why I’m doing it. That’s what keeps me driven.

Speaking of driven, you will have three books published this year: Patina (Atheneum/Caitlyn Dlouhy Books, 2017), Long Way Down (Atheneum/Caitlyn Dlouhy Books, 2017), and Miles Morales: Spider-Man (Marvel Press, 2017). In addition to being an author, you are also a speaker and a teacher. How do you find time to do everything?

I don’t sleep. I write on planes and in airports. I edit the manuscripts of my students in hotels. I do whatever needs to be done. Like I said, obsession. It’s tough but it ain’t boring, so I’ll take it!

Miles Morales is a bit of a departure from your usual writing subjects. Was it a challenge to write a Spider-Man novel?

The books all come out of me, out of my experiences, so I have an equal connection to all of them. But, of course, writing about a superhero was different. But only in the sense that I didn’t want to write a “superhero” book, but instead, a book about a kid who happens to also be a superhero. It was a nice stretch, and a lot of fun, and still me.

Miles Morales aside, your other characters and stories focus on the black experience. Are you writing for black people or for everyone?

I write about black people. But the misconception is that stories of black people aren’t for everyone, when the truth is, the stories of black people are the stories of America. My stories are contemporary, but there is nothing about today that is not about yesterday. My stories are also human, therefore, at the core of each are the things that connect us. But yes, I write about black people. And I’m unashamed and unafraid to do so. As a matter of fact, I’m honored to do so.

The We Need Diverse Books movement is very active. As a younger writer and someone who writes for a young adult audience, how long do you think we will need formal structures to increase diversity in publishing? Do you think this will ever be a non-issue because there will be so much variety available?

I’d like to believe so. But I also think that would display a bit of naïveté and even some hubris on behalf of us all. There is never a time where things aren’t changing, and with change comes discomfort, dissent, pushback, and ultimately, if we have the necessary channels in place, growth. But I think those channels have to be there.

“I have to remind myself everyday what I’m doing and why I’m doing it. That’s what keeps me driven.”

It seems that our country is going through a time of growing discomfort, dissent, and pushback, especially in regard to race. How do you feel your books and other diverse literature can help?

Books are empathy machines. Art, in general, has a way of tearing our egos down. Chipping at our walls. There has never been a time of unrest in this country when literature hasn’t been a valuable weapon against oppression. It allows us to see the landscape as it is as well as imagine a better world. It also creates capsules for posterity. James Baldwin said that he knew he wouldn’t be the marcher. He knew he didn’t have it in him to take up a sign and chant in the streets. But he still believed he had a role. He knew there would have to be someone to document these moments—that there would have to be a scribe so that generations to come could know of the shoulders on which they stand.

As a scribe for this generation, what can readers look forward to seeing from you soon?

Let’s just say, lots of things!