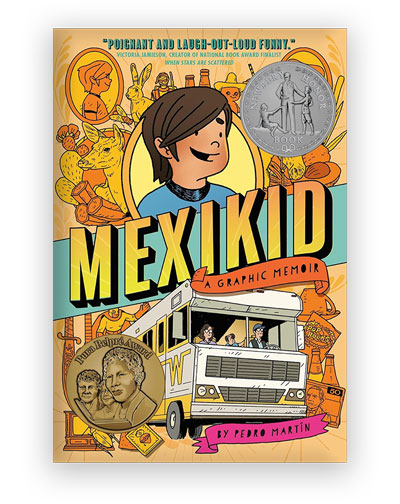

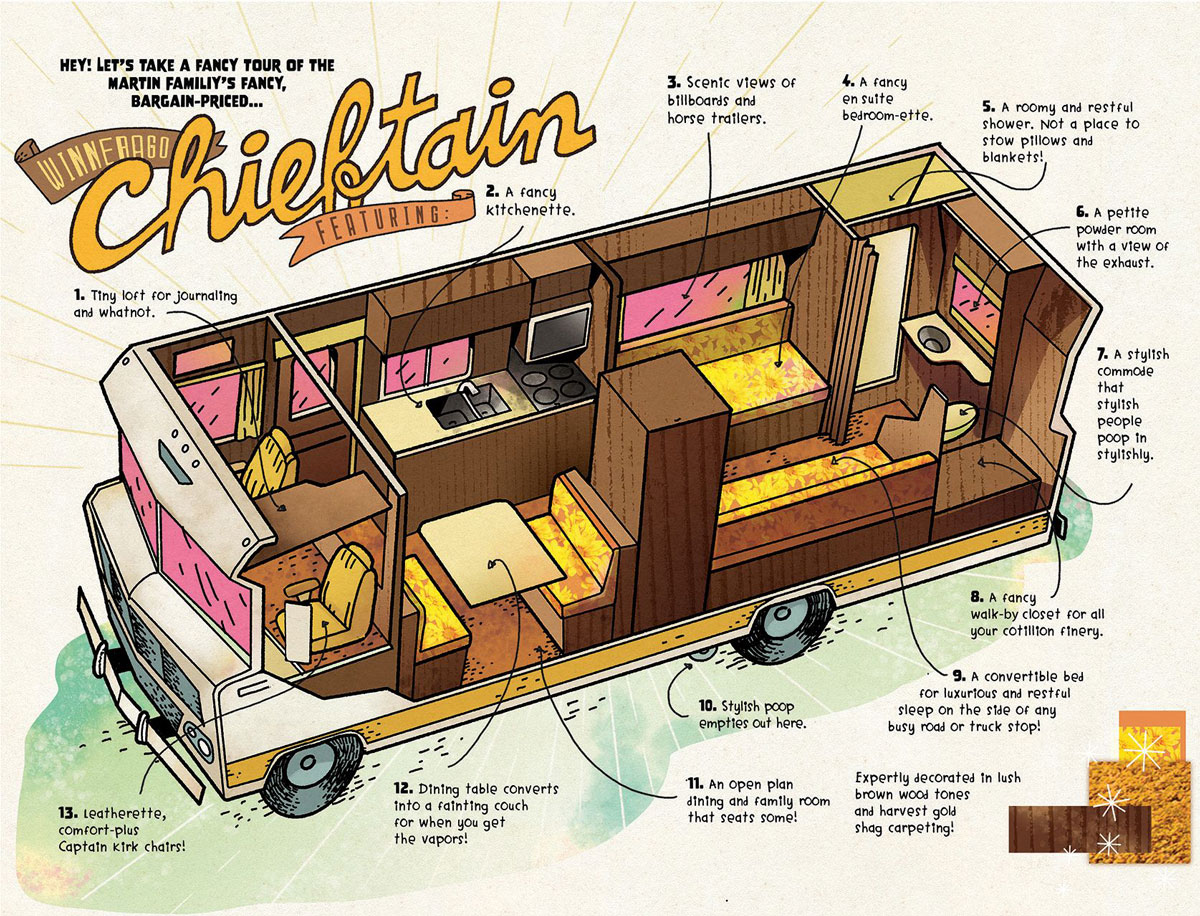

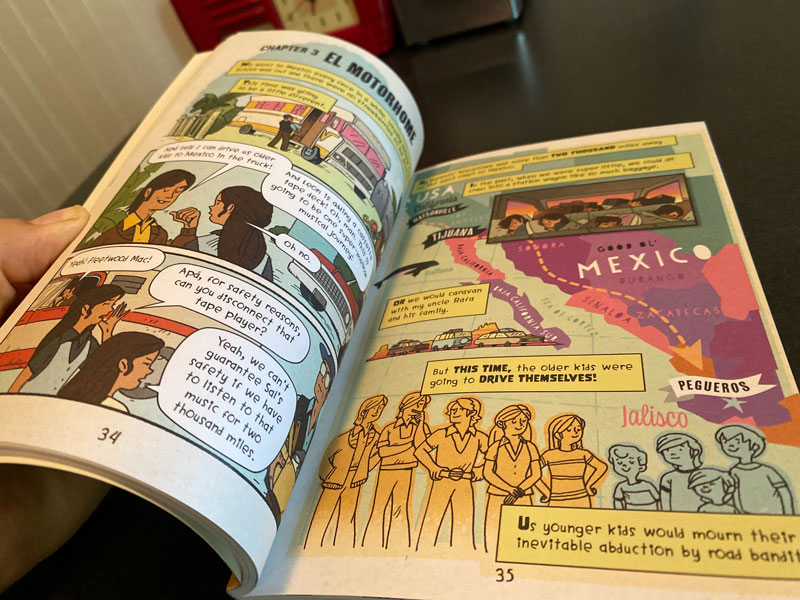

Mexikid (Dial, 2023)—Pedro Martín’s middle grade graphic memoir—features hilarity, family superhero stories, relatable sibling interactions, and an inspired exploration of cultural identity. The story, at times both laugh-out-loud funny and poignant, details the epic road trip that Martín’s childhood family took from California to Mexico and back. The book has also garnered a Winnebago-full of awards and honors, including an Eisner Award Winner for Best Publication for Kids and a Newbery Honor for debut author/illustrator Martín.

Here, Martín talks about his publication journey; sibling rivalry that lasts into adulthood (e.g., “Don’t tell him I said that. He’s still stronger than me.”); and the complex fashion in which memoirs are created from a fusion of emotion, true events, and storytelling.

How did you decide to share this story in book form?

Thanks for the great question. I’ve actually been sharing family and personal stories for a few years now in my online series, Mexikid Stories.

When I retired from my job as an artist at Hallmark Cards, I was looking for a new creative outlet. I had written several short comic stories about my family years before, and I happened to stumble upon them when I was unpacking my office. I remembered how much I enjoyed writing these stories, so I decided to try it again. But this time, I was going to share my stories with the world.

I wrote and published a new story almost every week for two years and then decided I wanted to do the same thing but in book form! Fast forward another year or so, I pitched Mexikid: A Graphic Memoir. In it, I detailed the story of that infamous trip down to Mexico to get my grandfather and bring him back to the U.S.

What approach did you take creating your first book? Did you start with the images, the words, or in some other way?

I had never attempted a project that big before, let alone written a graphic memoir. I didn’t know what I was doing, so everything was totally trial and error. The first thing I had to do was write the story. I wrote it like you would write a book, with dialogue and detailed description of what was going on. Then once the editor approved, I broke the whole thing apart and started the lengthy process of laying out and penciling all 320 pages.

Because I didn’t know what I was doing, I accidentally penciled 640 pages! My editor informed me that they could not publish a book that long, so I had to cut it in half! Oopsie! All in all, it took about eighteen months to write and illustrate the entire book.

How does your approach to writing and illustrating differ? Is one more challenging or more rewarding for you?

All the phases of the process had their ups and downs. But I think doing the final artwork was the most fun. When I’m writing, I can’t have any distractions, so I set my noise machine on “Sounds of the Ocean” and write and write. But when that part is all settled and done, I can turn on music or movies and have a grand old time drawing and painting.

Identity is a big part of this story. How have readers responded to your self-characterization of having “one heart belonging to both sides” of the Mexican-American border?

I have been happily surprised by how many people have come up to me since the book was published and said, “Me too!” Not only were trips like this commonplace for many first-generation kids like me, but we also shared the feeling that we didn’t 100% belong to either side of the border. I think we all collectively felt relieved that we were going through this together! We were all children of two cultures, and it was not only okay, it was cool!

I have been happily surprised by how many people have come up to me since the book was published and said, ‘Me too!’”

Memoirs are based on actual events from the author’s life, but they’re also dependent on that writer’s perspective, memory, and emotional truth. When readers ask you if your stories are true, how do you answer them?

I like to say my stories are 100% true 90% of the time. Seriously, I often struggled with the fear of misremembering an event. But then I realized that there was no possible way for me to give you a 100% accurate story when my brain and my heart are so tangled together. Emotion is the core of memory. It’s the thing that we hang on to even more than facts. So, when you look back on an event, the first thing that pops into your head was what you felt in the moment. And even then, those feelings change over the years as you mature and gain perspective.

Then you need to take into account the process of telling a story. In a memoir, you want to tell the story about the time something happened to you that changed you in a clear and understandable way. But life is messy and sometimes boring, so you might want to restructure the story so that the reader is more apt to follow your journey.

Pedro Martín’s Four-Panel Approach to Writing a Story

I tell kids all the time: Humans are storytelling machines. That’s all we do all day long! We tell stories. Since the caveman days, we tell stories to help others survive!

“See that saber-toothed tiger over there? It ate Timmy’s face off yesterday. Don’t be like Timmy. Stay away from that saber-toothed tiger.”

“Great story, Ogg. One for the books!”

So, to kids and teachers, I say: Start telling stories. Short stories are the easiest.

The funniest are the ones where something you did went wrong. And then poke fun at yourself a little for it. Not only will it be funny, but you might also learn a lesson about yourself in the process.

Give yourself four panels to tell the story. You can take an 8½ x 11 piece of paper and fold it into quarters.

Panel 1 sets up the characters and the situation. For example: “I have to comb my hair before I go to school.”

Panel 2 is usually the character’s attempt to do the thing they need to do, but they get in their own way: “I’m in such a hurry, I’ll comb my hair on the way to school to save time. I don’t need a mirror!”

Panel 3 is usually where everything goes wrong: “I realize I had gum in my hair and now my comb is stuck too!!”

Panel 4 is usually where you decide to try and salvage the situation but make it worse: “I decided to put stickers on the stuck comb to make it look like a new accessory I invented! No one is on board.”

I like to say my stories are 100% true 90% of the time.”

In what ways did you shape your story to draw out the humor?

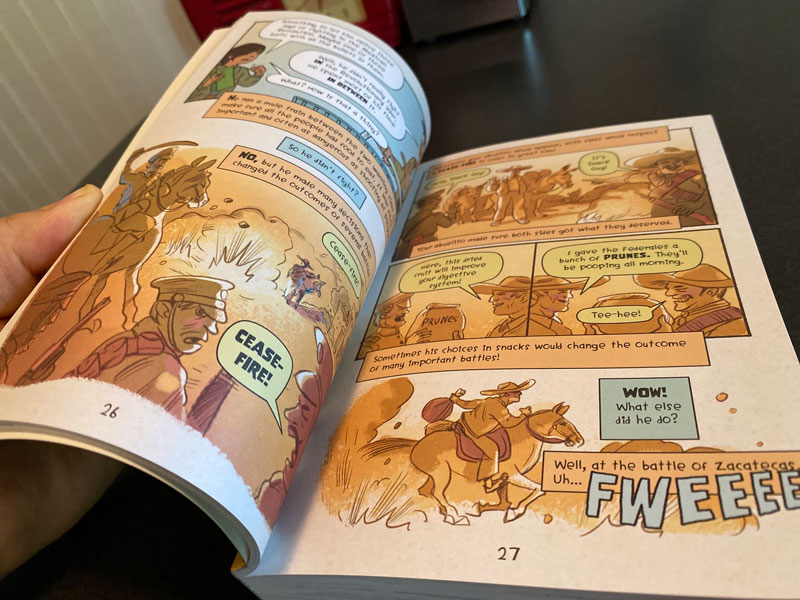

Everyone in my family is very funny. But there was no way to capture all the humor from conversations I had all those years ago. I had to approximate a lot of the conversation, keeping in mind the individual personalities and what I figured they might have said at any given moment.

Did you worry that anyone in your family might get upset about you making this personal story so public?

As far as my family goes, they have been telling their versions of this story for years. When I told them that I was going to write this book, they all said, “Great idea. You should totally do it.” And, “Let us know how it goes.” Which really means: “We don’t think it will happen.” And, “Stop bugging us.”

So legally, I think I’m cool.

Could you talk a bit about how your family’s storytelling traditions helped shape Mexikid?

Everyone in my family is an exceptional storyteller, especially my apa. As far back as I can remember, he would regale us with stories of hardship and pain from his childhood, but at the same time make them funny and inspiring. I always wanted to do that with my stories.

My brother Hugo is a reporter/editor for the LA Times; he’s a real-life paid storyteller! And my brother Leon sends me stories all the time. His stories are funny and poetic. I feel like he could do what I do if he could draw.

But he can’t. He’s terrible!

Don’t tell him I said that. He’s still stronger than me.

What is your favorite part of creating books for young people?

Everything! I especially love doing classroom visits after they have read the book. I love the questions kids have, but I also love sharing my process. It looks hard, and it is, but it’s also within everyone’s grasp. Seriously, if I can tell my story, you can too.

If I can tell my story, you can too.”

What do you most hope that young readers will take away from reading Mexikid?

First and foremost, I hope the readers find it funny and fun. That’s always my ultimate goal—to entertain. Aside from that, books are empathy machines. I hope that kids either see a little of themselves in the book, or they learn to appreciate the lives and struggles of kids who might be different from them culturally. And in turn, see what we all have in common: older siblings who are jerks sometimes.

Books are empathy machines. I hope that kids either see a little of themselves in the book, or they learn to appreciate the lives and struggles of kids who might be different from them culturally.”

Are you working on other books for young readers?

I am currently working on the sequel to Mexikid. And as soon as I’m done with that, I’ll have more Mexikid stories to share online.

What are the best ways for educators and librarians to connect with you or to follow you on social media?

The best place to see most of my stories is at mexikid.com or @mexikidstories on all social media.

To download “An Educator’s Guide to Mexikid,” visit here.