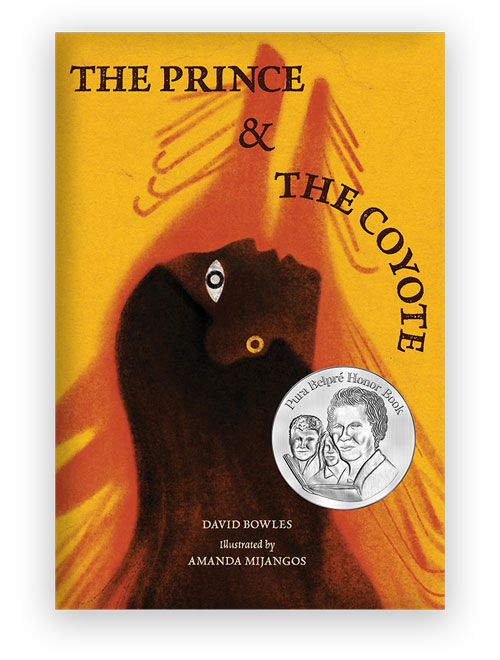

David Bowles’ character “Fasting Coyote”—based on the real life of poet and ruler Nezahualcoyotl—pulled off many of his amazing accomplishments while still a teenager, so it’s little wonder that Bowles’ action-packed YA book is relatable to a teen audience. In The Prince & the Coyote (Levine Querido, 2023), Bowles relates the absorbing story of this little-known but highly influential figure in the early history of the Americas. Illustrated by Amanda Mijangos, the title has gained a notable array of honors, including being named a Pura Belpré Honor Book, listed as one of the 10 Best Books of 2023 by BookPage, named a Best YA Book of 2023 by Kirkus, and included as one of the 2024 Best Children’s Books of the Year by the Children’s Book Committee/Bank Street College of Education.

Here, Bowles talks with Lisa Bullard about the inspiration he takes from the Mexican American community on the border, how his time as a teacher led to his writing career, and why focusing on young readers makes him his “best self.”

How did you come to write The Prince & the Coyote which features a groundbreaking historical figure that many people outside of Mexico have likely never heard of?

I first learned of Nezahualcoyotl when buying things in Mexico with a 100-peso bill, which for the longest time featured his face and, in small print, the Spanish translation of a poem of his about loving his fellow humans. After college, my interest in pre-Spanish-Invasion Mesoamerica grew, and I began to learn Nahuatl, the language Nezahualcoyotl and his people spoke (still used today by 1.5 million individuals in Mexico and Central America). Why? Because I wanted to read the words of Indigenous poets and historians without the filter of often boring, pedantic translation. I was certain that the original texts were richer than they seemed at first glance and I was right. I was especially captivated by the voice and musicality in the poetry attributed to Nezahualcoyotl, some of it written when he was a teen, orphaned and on the run from enemy forces.

Digging into what is known of his life, I felt a real kinship with the adolescent poet and future architect of the Aztec Empire. Like me, he was left without a father just when he needed such a figure most. Like me, he was a bright, capable young man with a talent for music and poetry. Like me, he was of mixed ethnic heritage, his mother and father from different cultures that were often at odds with each other. Years into my research about fifteenth-century Nahuas and the translation of their surviving songs, I realized that young people today should have the chance to learn about this amazing figure, too. I was uniquely positioned to write a novel of historical fiction with Nezahualcoyotl as the protagonist.

I realized that young people of today should have the chance to learn about this amazing figure.”

What were your biggest challenges in creating the book?

Taking a world so different from ours—Anahuac in the early 1400s—and making it accessible to a modern reader presented many interesting challenges. But I kept Nezahualcoyotl’s voice at the forefront at all times; in fact, I have interwoven translations of his poetry throughout the text, alongside new poems written in his captivating style. They anchor the narrative in Nezahualcoyotl’s personality so readers don’t get too overwhelmed by the strangeness of Mesoamerica. Consequently, I hope, teens and adults will come away with an appreciation for how deeply human and relatable his struggles were. Given the fact that most people only get a fleeting, often negative view of “Aztec” society, the universality of the lessons Nezahualcoyotl learns is valuable in pushing back against a lot of unfair portrayals.

How did you go about doing the extensive research necessary to tell the story?

By the time I decided to write the book, I had done the bulk of the research already (though not specifically with this project in mind). That consisted of learning Nahuatl and reading literally every colonial-era text written by Nahuas in their native language about their history and culture, especially the two poetry codices. Reading those primary source documents alongside critical analyses by modern archaeologists, anthropologists, and linguists helped to dispel some of the myths about Nezahualcoyotl that emerged after the Spanish Invasion.

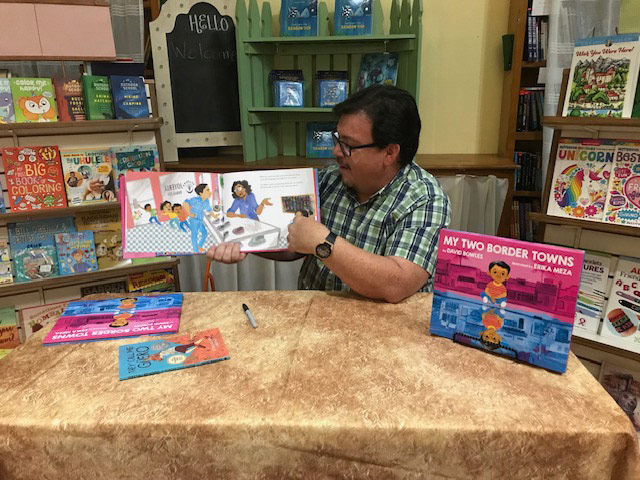

David reads from his award-winning picture book My Two Border Towns.

What tips would you like to share with students who are tackling their own research projects?

There’s a point I often underscore with young people doing research: don’t just believe whatever others claim (especially not what they post on the internet). Verify it with several other sources that are trustworthy. And check with real-life people who might know the facts, who were there when the events happened.

I was fascinated by the philosophy of dualities (as opposed to binaries) as presented in The Prince & the Coyote. Could you say a bit more about that?

Different from Middle Eastern and European belief systems, Indigenous Mesoamerican philosophy doesn’t hinge on binaries, in which something is either one thing or its opposite (like good and evil, night and day, male and female). Instead, the cosmos is seen as full of dualities, which are more like a sliding scale from one possible end to another (example: night lightens into dawn and then morning and later the brightness of noon before fading toward dusk and then night again). As a result, the apparent conflict between chaos and order, for instance, is actually a constant adjustment of the balance between two essential and complementary elements. Mesoamerican conceptualization of gender is also on a sliding scale, so that in addition to male and female, there are gradations in between, like xochihuah and patlacheh (which correspond somewhat to modern concepts of non-binary or trans identities).

What is your favorite part of writing for young people?

The immediacy of emotion, the freshness of perspective, and above all, the unwavering hope that the world can and must get better. Young protagonists are our very best teachers. They remind us of the infinite possibilities that life can offer. I am my best self when I write from the point of view of a kid.

Young protagonists are our very best teachers. They remind us of the infinite possibilities that life can offer. I am my best self when I write from the point of view of a kid.”

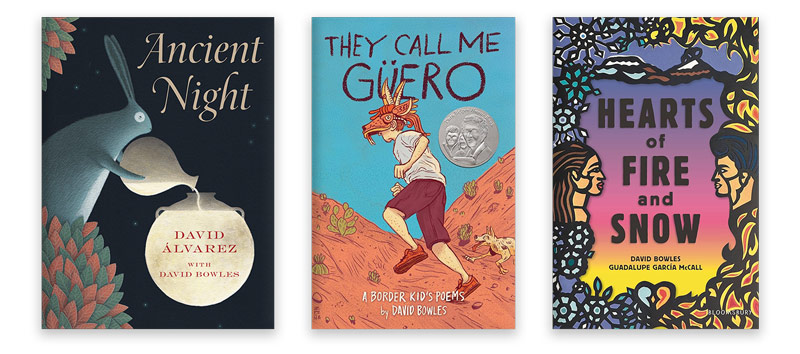

Your books cover such a wide range. They include the picture book Ancient Night with illustrator David Alvarez (Levine Querido, 2023); middle grade books such as the graphic novels in your Tales of the Feathered Serpent series and They Call Me Güero: A Border Kid’s Poems (Cinco Puntos Press, 2018); and Hearts of Fire and Snow, a fantasy romance with Guadalupe García McCall (Bloomsbury YA, 2024). How does it serve your creative energy to take on so many different types of projects?

I once told my agent that I have 200,000 words inside me each year that I need to express. That can be divided up in lots of ways and among many different audiences (I’m sure readers thank me, because trying to keep up with everything I produce would be exhausting). More importantly, I love the act of writing, the energy of being in the midst of creating. I don’t see it as a chore at all, though I will admit that picture books are ironically the toughest to write. With a text that short, every word counts and must be thought about thoroughly.

David narrates the audiobook for Ancient Night, illustrated by David Álvarez.

What do you see is the thing that brings all your work together?

When you look at my forty books (counting translations as well), you’ll see that they do arise from a singular (if complex) interest: the Mexican American community on the border, our culture’s origin in Mexico, and Mexico’s roots in pre-Invasion Mesoamerica. As I seek to better understand my family and neighbors, I delve deep into our collective past and share what I learn with the folks I love and with those who find our lives compelling.

Your background includes time as a middle school and high school English teacher. How did those experiences impact the writing you do for young readers?

It was when I was a middle school English teacher that I discovered my calling as a writer of books for young people. In my third year of teaching, I had a group right after lunch that could not connect with the literature in the state-adopted text because of cultural and linguistic barriers. So, I started retelling, in short story form, legends that my Grandmother Garza had told me when I was a boy, and the students became super excited. I taught them how to revisit other stories we shared (as well as historical events preserved in their families’ lore) and retell them with their own unique voices. The ownership and relevance that were injected into our classwork were frankly revolutionary.

It was when I was a middle school English teacher that I discovered my calling as a writer of books for young people.”

Do you have any advice from your experiences as an educator that you’d like to pass along to teachers?

I urge teachers to find ways to draw from their students’ local funds of knowledge, to recognize and value the understandings they already possess, and to connect those to new learning.

How did your childhood and teenage years shape you as a writer?

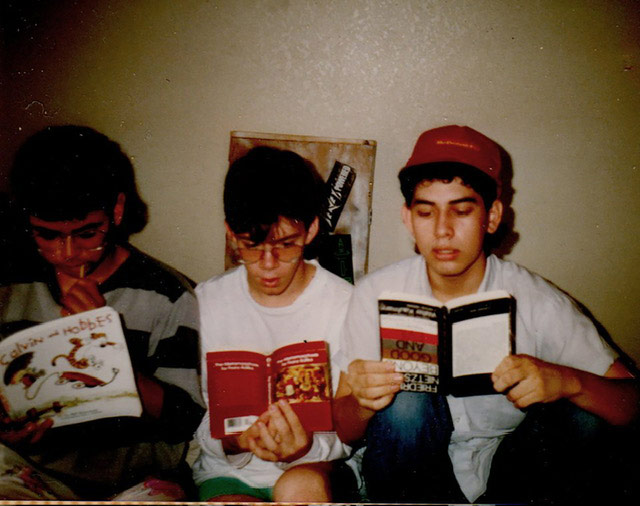

My love of the tales my grandmother told me led to my love of reading, as she encouraged me (perhaps with some exasperation at all my demands for more spooky stories) to seek adventure and answers in books. Reading a lot from an early age literally transformed me so that I was devouring college-level texts by the time I was in sixth grade. Add to that a pair of amazing mentors (in eighth and eleventh grade) who showed me that poetry was the clearest lens for viewing the world, and that I had genuine talent with words, and you’ll understand why I wrote my first novel at the age of seventeen for a contest sponsored by Avon Books. (I didn’t win, by the way, but I wrote a freaking book! Pretty amazing.)

David at age 17, flanked by his buds Gustavo Acosta (left) and Ranulfo Márquez (right).

What’s your best advice for young people who want to be writers or pursue some other creative activity?

Practice your craft as often as you can, preferably a little bit every day. And while you will probably start by imitating the work of the people you admire, remember that you are your own person with your own identity and roots. Find a style that’s unique to you. Tell the stories that no one else can tell quite like you can. Lean into who you are. Readers want that. Some of them frankly need your story.

Tell the stories that no one else can tell quite like you can. Lean into who you are. Readers want that. Some of them frankly need your story.”

What would you like to share with your fans about your forthcoming books?

I’ve got a couple of graphic novels coming up: The Hero Twins and the Magic of Song (Lee & Low) in October 2024, and Clockwork Curandera: Robots of the Republic in April of 2025. Also, next year (finally) will see the publication of the fourth book in the Garza Twins series, Wings Above the Burning Earth.

What are the best ways for educators and librarians to connect with you or to follow you on social media?

I can be found on most platforms under the handle @DavidOBowles—but I also post a lot of content on my website (davidbowles.us) and my Medium page (davidbowles.medium.com), which features many articles I’ve written about pre-Invasion Mesoamerica and the Nahuatl language, among other cool topics.