Traci Sorell, an award-winning author and a Cherokee Nation citizen, has written a wide range of books for readers of different ages, including both fiction and nonfiction, contemporary and historical. Sorell’s work illuminates important issues in the lives of people who have often been ignored or misrepresented in the past, offering readers new ways to consider history and broaden their perspectives.

Here, Sorell talks with Lisa Bullard about the storytelling tradition she grew up with, activities that classrooms can use to dig deeper into Native history and culture, and the joy she finds in being part of bookmaking teams.

What was it like to grow up as part of the Cherokee storytelling tradition?

Cherokee people have always shared history, news, and other types of stories through the spoken word. That tradition continues today, whether the stories are told in Cherokee or in English. After the Cherokee people adopted the syllabary Sequoyah invented to write in the Cherokee language, then storytelling expanded into the written form.

Growing up in a Cherokee community, I knew about this history and heard stories from my Cherokee relatives. Those stories gave me a sense of belonging, communicated the values of our people, and helped me to experience story in a vibrant and fun way.

How has that tradition helped you craft your books for young readers?

I hope through the words I craft that readers find a dynamic story that enlightens, informs, entertains, or just makes them feel like their time with the book was well spent. I want them to see that Native people have always been here and will always be here—making contributions, exercising their sovereignty, speaking their languages, and advocating for all to be cared for, including the land, water, air, plants, and animals.

Native people have always been here and will always be here—making contributions, exercising their sovereignty, speaking their languages, and advocating for all.”

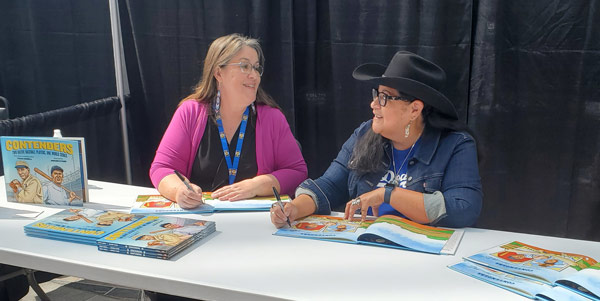

Traci Sorell and Arigon Starr signing Contenders at the IndigiPopX Convention in Oklahoma City.

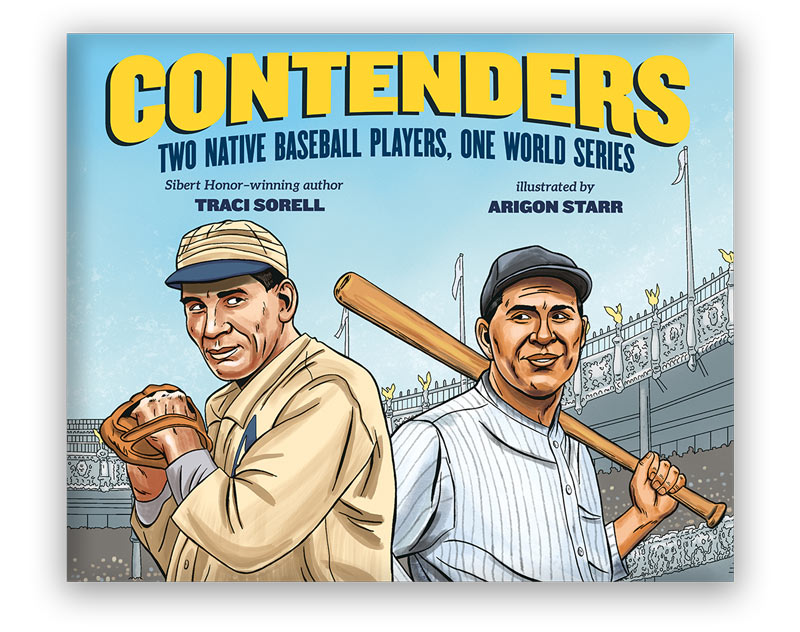

Your nonfiction picture book Contenders: Two Native Baseball Players, One World Series (Kokila, 2023) illuminates the lives of the first two pro baseball players from Native Nations to become opponents in the 1911 World Series. What drew you to their story?

I’m a lifelong baseball fan, but I hadn’t heard about pitcher Charles Bender (White Earth Ojibwe) or catcher John Meyers (Santa Rosa Cahuilla) playing against each other in the championship series until my husband was reading a book where that was mentioned. My curiosity was piqued to learn more about them, how they got to that history-making moment, and what their lasting contributions were to our national history.

What do you hope that young readers take away from the story of these two inspiring individuals?

My hope is that readers see that there is not a single path to get where you want to go. Also, we all have gifts and abilities we can use to help, inspire, and contribute. I hope after reading this book they understand challenges will always be present, but they are not alone and can work alongside others to make life better for everyone.

Teacher’s/Discussion/Activity Guides

Your novel in verse (with co-author Charles Waters), Mascot (Charlesbridge, 2023), takes a nuanced look inside a contemporary community that is grappling with polarized opinions, and you skillfully incorporate seven different viewpoints. Can you talk about the challenge of presenting so many viewpoints while still making each of the characters feel relatable?

Charles Waters and I collected over seventy-five sources (newspaper articles, academic papers, dissertations, and more) about Native-themed mascots and their effect on students, both Native and non-Native, in K-12 education. We learned so much by doing that.

It also showed us that we had to have a variety of characters from various backgrounds to represent what we saw in the research. To match the book’s setting and to have it read authentically, we also matched the characters to the demographics of those living close to Washington, DC. Because some characters have identities that neither Charles nor I have, we enlisted the help of others who do have those identities to read and give us unfiltered, honest feedback about the representation on the page. All of that helped us craft how these seven characters would act on this issue.

Frané touring the Cherokee Nation reservation with Traci Sorell and Will Chavez, assistant editor and photographer for the Cherokee Phoenix newspaper.

Mascot also provides fantastic examples for students who are learning to prepare their own persuasive essays or oral presentations. Do you have additional advice to offer those students?

Regardless of how you may feel or what you think about any given subject, study it from a variety of angles. Think about who or what is directly affected, less directly affected, and who might not be affected at all. Now it’s time to go beyond your own thinking or what someone has told you. Look up the data and read the impact of the issue on those most affected.

Regardless of how you may feel or what you think about any given subject, study it from a variety of angles.”

You and Charles Waters collaborated on Mascot, and you also allow “room” for the illustrators of your picture books to retell the story in their own way. Based on those collaborative experiences, do you have suggestions for students who are working as part of a team in the classroom?

Each of you has strengths, experiences, and viewpoints that are different from others. Making a book together requires the combining or collaboration of two or more people, so no one person gets to say how everything will be written, illustrated, or designed. Everyone provides their input.

When I write a picture book, I think about wooing or enticing the illustrator. They must tell more than half the story in the art because of a picture book’s limited word count. The majority of the work is on them as the storyteller. So, my writing must be lyrical and tight, prompting their mind to fill with images that they can’t wait to create to elevate the story far beyond the text on the page. I never tell them what to illustrate; I just craft words that I hope will inspire them.

Does your creative approach differ when you’re writing fiction versus nonfiction? Or when you’re writing picture books versus books for older readers?

I always start with “What do I know?” and “What do I not know yet?” whether I’m writing fiction or nonfiction. I then must figure out the best age range for the story I want to tell and what I think will be the most compelling format. Answering all these questions not only takes time, it can also delay a story being written, as I may need to work on my craft more (reading and studying the format, age range, etc.) before taking on drafting the story. But I like to challenge myself. It keeps me interested and motivated to do that.

I always start with ‘What do I know?’ and ‘What do I not know yet?’”

What is your research process like? Do you have suggestions for students who are learning how to do effective research themselves?

I must find trusted source materials on whomever or whatever I’m writing about. That can be tricky, as a lot of what has been written about Native Nations, their citizens, and their history is inaccurate. Nearly every Native Nation has its own website, so that is a great place to start for sources (people to interview, cultural resources, books, etc.). Just using Google or Wikipedia can yield a lot of problematic and inaccurate information on many subjects. Go get as close to the subject as possible. For Contenders, I read interviews with each major leaguer and books written about them, connected with their families, and visited museums. Then I started comparing the various sources to determine the reality of these two men’s lived experiences in baseball.

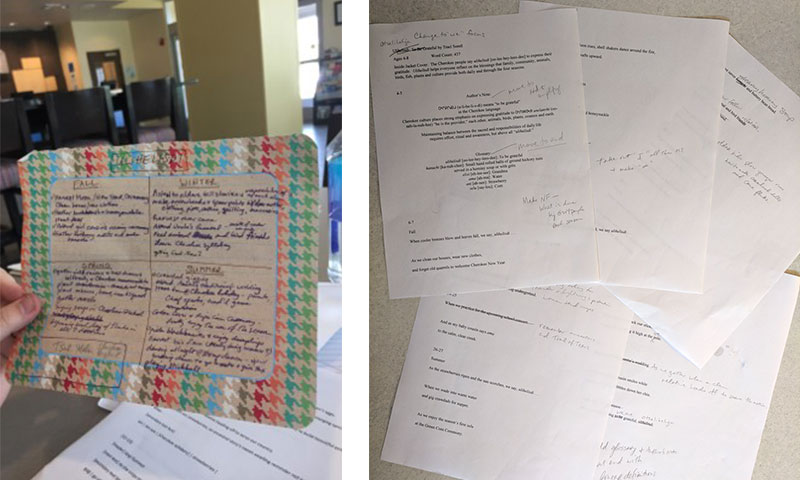

Brainstorming pages from We Are Grateful: Otsaliheliga and Traci’s markups.

What’s your best advice for young people who want to be writers?

Read, read, and read some more. Reading hundreds of recent books in whatever format and for whatever age group you want to create for is key. I check out lots of books from my local library every month for inspiration, education, and to stay current on what is available for young people to read.

It’s critical to study how the story appears on the page, whether you want to write, draw, or do both. Your school and public libraries are places to check out the most recent books to see what authors, illustrators, and author-illustrators are doing. The more you read and study, the easier it becomes to see patterns; understand story structure; see where the text may start the story, but the art carries it far beyond what the text shares; and more.

Read, read, and read some more.”

Do you have suggestions for teachers and students who want to immerse themselves more deeply in your books? Perhaps some ways to compare and contrast your titles?

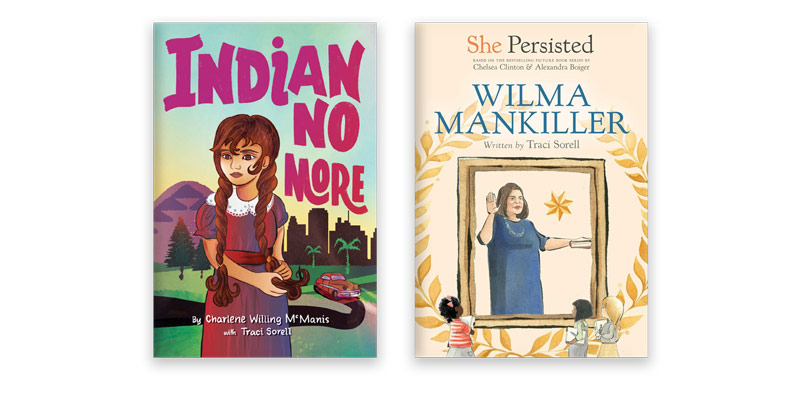

Read Indian No More (Tu Books, 2019), which is historical fiction, and She Persisted: Wilma Mankiller (Philomel, 2022), which is a nonfiction biography, to learn more about the impact of federal termination and relocation policies on Native children and their families.

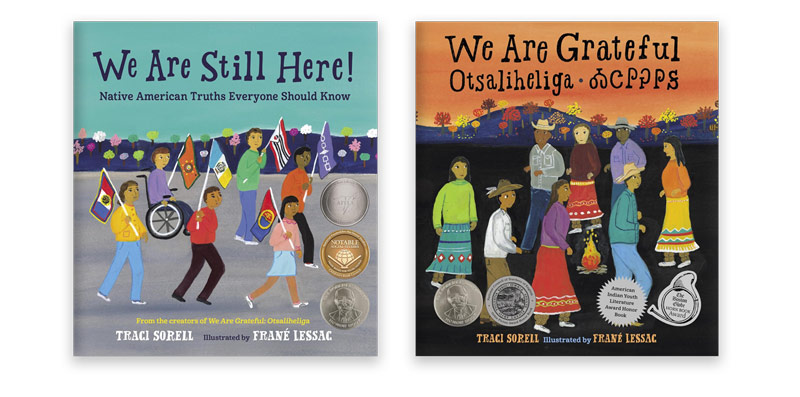

Examine We Are Still Here: Native American Truths Everyone Should Know (Charlesbridge, 2021) and then We Are Grateful: Otsaliheliga (Charlesbridge, 2018). The first book gives readers an overview ranging from the history to the contemporary realities of Native Nations in the USA since 1871 (generally when they disappear from mention in K-12 curriculum). Compare that with the history and contemporary realities shared in the second book, which focuses on one specific Native Nation—the Cherokee Nation.

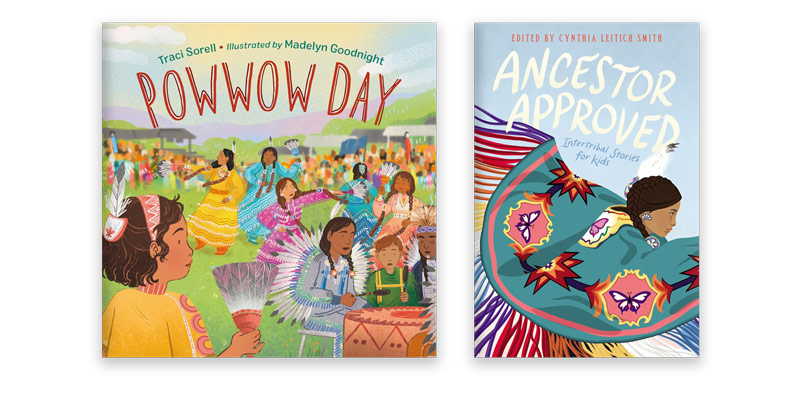

Read the picture book Powwow Day (Charlesbridge, 2022) and then the short story “Secrets and Surprises” in Ancestor Approved: Intertribal Stories for Kids (Heartdrum, 2021). Write down what you learn from the picture book about River and her Ojibwe family and community through the art and the text. Contrast that with the short story form and what is learned from a story told from her older sister’s perspective.

What’s your favorite part of creating books for young people?

Being part of the bookmaking team gives me so much joy! I’m doing my part to create the story through words, but others help me with that process. I use photos, interviews, books, maps, and other sources people have created to help me craft the story, whether fiction or nonfiction. Numerous people read my words and give me their unfiltered feedback. I believe lots of people’s names should be on the cover alongside mine because I could not write the books without them.

What would you like to tell your fans about your forthcoming books?

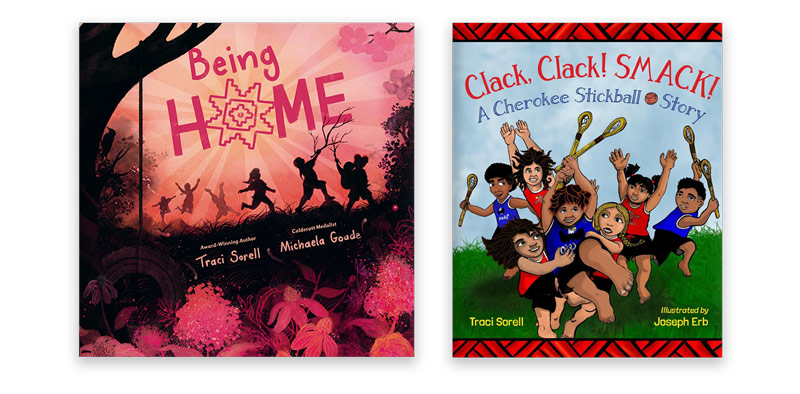

Being Home (Kokila, May 2024), with Caldecott Medalist Michaela Goade, follows the celebratory journey of a Cherokee child moving from the city where they’ve always lived to the ancestral lands where the rest of their relatives live.

Clack, Clack! Smack! A Cherokee Stickball Story (Charlesbridge, August 2024), with Joseph Erb, shares the experience of Vann, who struggles to make plays when his team competes against others in a stickball game. There will be two versions of the book—one in English and one in the Cherokee syllabary.

And there’s more fiction and nonfiction on the way after those!

What are the best ways for educators and librarians to connect with you or to follow you on social media?

My website, tracisorell.com, is always the best place to find out the latest about my current and forthcoming books as well as to access free classroom guides and downloadable materials.

Find me on Instagram @tracisorellauthor or via Bluesky @tracisorellauthor.bsky.social.