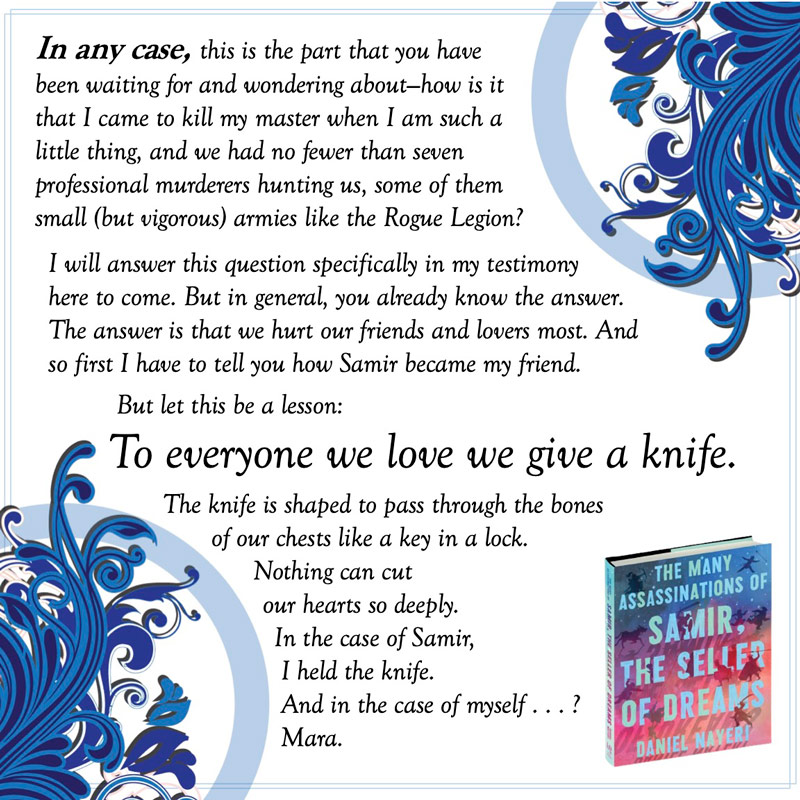

From his opening line— “The first time I was stoned to death by an angry mob, I was not even a criminal”—the twelve-year-old narrator of Daniel Nayeri’s newest book, The Many Assassinations of Samir, the Seller of Dreams (Levine Querido, 2023), pulls readers into an adrenaline-packed tale that is rich with history, adventure, and the complex emotions that come with trying to build a found family. Set along the Silk Road in the 11th century, the story is told through the eyes of an orphan dubbed Monkey and captured brilliantly through full-color illustrations by Daniel Miyares. Like Nayeri’s Printz Medal winner, Everything Sad Is Untrue (a true story) (Levine Querido, 2020)—an autobiographical novel about a young Iranian refugee who narrates his story from an Oklahoma middle school—this new book is a masterful example of storytelling layered with surprising twists and laugh-out-loud humor.

Here, Nayeri talks with Lisa Bullard about the challenge of writing kid narrators, some alternative approaches to storytelling, and what he sees as art’s greatest achievement.

In The Many Assassinations of Samir, the Seller of Dreams, you bring your setting—a time and place in history that is perhaps little known to many American readers—to vivid life on the page. What inspired you to set Monkey’s story in this location?

When someone says the “Silk Road,” the first visual that comes to mind is a caravan of camels travelling across a sand dune, piled high with merchandise. And that’s somewhat accurate. The Silk Road was a network of trade routes that covered several topographies from Eastern China to Baghdad. Camels were common for the shifting sands in the Taklamakan Desert, where their webbed toes helped them quite a lot, but yaks were common in the Pamir Mountains. The time period spans from the 4th century to the 11th, so we’re talking about an era that is almost three times longer than all United States history. A lot happened during that time. So, you can imagine it’s a giant stretch of land, covering a vast array of cultures, over a huge stretch of time. But even so, I became fascinated with the lives of the merchants who made those trade routes their home. I wanted to know what they were like, what sorts of stories they valued most, what they dreamed about. Samir, a galivanting teller of tales, was born out of those wonderings, and soon, his polar opposite, the sincere and dour Monkey.

What were the complications in researching and creating this story?

The biggest complication to research is always language. There are still so many historical documents left to be translated. The hardest element to convey to readers is that people haven’t changed much over the centuries. If I could simply get readers past the unfamiliar nouns (samovars, caravanserais), I knew they’d be familiar with the adjectives (a lonely orphan, a hopeful liar), and therefore, the deeply universal verbs (desire for love, longing for family).

The hardest element to convey to readers is that people haven’t changed much over the centuries.”

Both The Many Assassinations of Samir, the Seller of Dreams and Everything Sad Is Untrue (a true story)—available in a new paperback edition on August 8—ask questions about truth: who gets to define it, in what ways it matters, why people sometimes avoid it. I especially admire the way you manage to signal readers about the “truth” of a character’s situation even though it’s clear your character doesn’t yet recognize that truth. What is the role of truth in a story, in our understanding of ourselves, in life? What questions do you most want young readers to ask themselves about the concept of truth as they read your books?

That’s a very insightful question. We are programed a bit these days, to read stories looking for the “good guys” and the “bad guys,” and we want one side to deal in the truth and the other to be mistaken at all times. In fact, I notice that we sometimes even collapse the ability of the villains to speak particularly evil lies, even when they’re clearly wrong-headed to do so. But in this world, there are partial truths, and soothing delusions, and lies of omission as well as commission. I would love young readers to become much better versed at spotting beautiful lies and uncomfortable with any truth they haven’t verified recently. But fundamentally, the truth is all we have in a world otherwise overrun with lies, and the greatest achievement of any piece of art, in my opinion, is to be useful in determining which is which.

The truth is all we have in a world otherwise overrun with lies, and the greatest achievement of any piece of art, in my opinion, is to be useful in determining which is which.”

The narrators of both these stories—Monkey as an orphaned child traveling the Silk Road and Khosrou/Daniel as an Iranian refugee in Oklahoma—have been significantly shaped by living as displaced people. What was the challenge for you in writing about that element of their stories?

In some ways, the displaced character is a challenge because they must explain where they’re from more than usual, and that creates a lot of “telling” rather than “showing,” which is an accepted no-no. But in other ways, the displaced character is the perfect narrator because they need the new place explained to them. They don’t take their present circumstances for granted. They organically want to talk about what is happening. I find one of the most challenging elements of first-person kid narrators is that a lot of kids don’t want to share so much. The narrator always must be a precocious chatterbox for the author to get the story out. To have that naturally in the [displaced] character is a blessing.

Your novels have amazing “read-aloud” potential. In what ways has your writing style been influenced by oral traditions of storytelling?

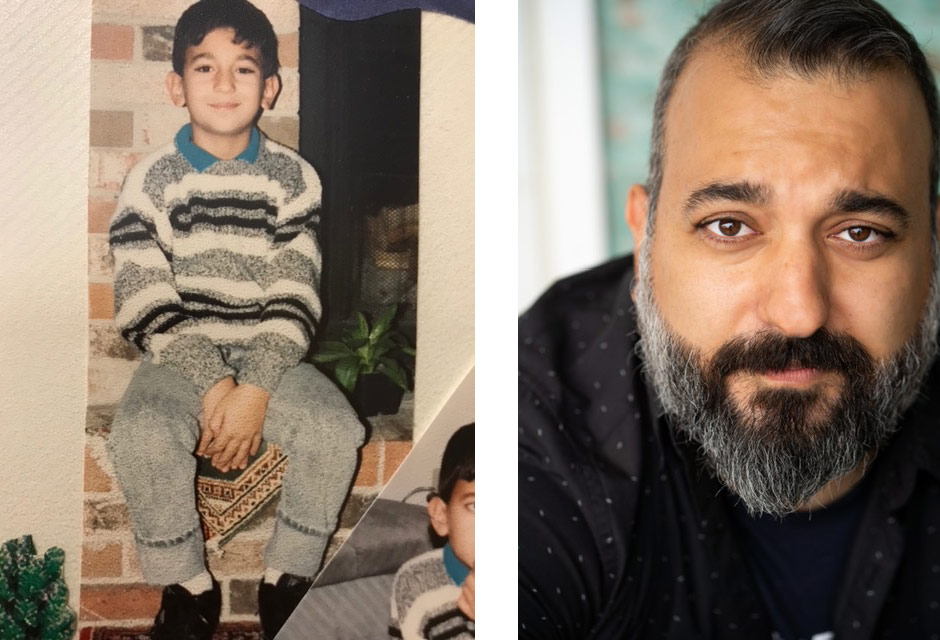

I’m working on a picture book right now about this very topic. That is, when I was a kid, the best stories came from a man named Abbas, who was the storyteller in his village. I would sit on my father’s lap alongside all the other kids, and we’d listen to his versions of The Arabian Nights and Persian folktales. I think about that experience every time I sit to write a story. I want young readers to feel the same way.

When I was a kid, the best stories came from a man named Abbas, who was the storyteller in his village. I would sit on my father’s lap alongside all the other kids, and we’d listen to his versions of The Arabian Nights and Persian folktales. I think about that experience every time I sit to write a story.”

Do you read your work aloud as part of your writing/revision process?

One of my favorite aspects of storytelling is to read it aloud and watch as the story changes slightly to suit the mood of the audience, the constraints of the environment, or the goals of the storyteller. In fact, I prefer it sometimes. If ever I’m asked to read a passage from my books, I find myself making edits on the fly and kick myself that I can’t change the printed versions.

This is also why I love it when teachers and librarians share their read-aloud practice or encourage students by accepting audio books as “reading.” I know teachers are in a bind on that one. They still must encourage actual reading, after all. But to hold that in balance with the notion that stories can be experienced orally, I think is the ideal way forward.

Both these books are not only wonderful examples of storytelling, but they also address the nature of storytelling itself. In fact, at one point in Everything Sad Is Untrue, the young narrator responds to his teacher by saying that she is “beholden to a Western mode of storytelling.” Can you talk a little about some of the different modes of storytelling that have influenced your writing?

The narrator is being a bit cheeky there when he says, “Western mode of storytelling.” In my mind he’s referring to class assignments kids have around his age that teach narrative structures like Freitag’s Pyramid, the Hero’s Journey, or Three-Act Structure. Here in the States, we develop such fine-tuned media literacy because of film/TV that we often hear things like, “The climax never paid off,” or “That story was nothing but exposition.” Those are technical terms that we’ve casualized because everyone understands what we mean when we say that. And I have to admit, I feel deeply satisfied when I see three-acts perfectly crafted.

But there are other ways to experience stories, of course. The Arabian Nights doesn’t follow the structures I mentioned above. Authors like Italo Calvino (my favorite) often break those structures. The mixture of those two (oral tradition/folk tales/Arabian Nights and Calvino) are what made me love the more inventive forms.

What suggestions do you have for educators and librarians who want to build that broader understanding of stories into their classroom discussions?

I think a lesson on different story structures would be fascinating. In addition to Freytag’s Pyramid, Kurt Vonnegut had a series of “story shapes” that would be fun to discuss. Telling a story backwards, in pieces, or as a list are all fun ways to give students an engineer’s approach to constructing stories.

Telling a story backwards, in pieces, or as a list are all fun ways to give students an engineer’s approach to constructing stories.”

You mentioned you’re working on a picture book about a storyteller. What else would you like to share with your fans about your upcoming books?

What an incredible idea, to have a readership out there. If that’s true, and they’re reading this, hello friend. I hope I’ve met your expectations, whatever they are. I’ve been working on a lot of stories within stories lately, where the frames shift as much as the pictures. I know that sounds vague, but I think they’ll be intriguing. There is the picture book about a storyteller in Iran. In the short thirty-two pages, we dive into the story, then out. There’s a graphic novel series coming that plays with the pulp stories that had hosts at the beginning to introduce the tales (like Rod Serling in The Twilight Zone) … but in this one, the hosts have their own story occurring at the same time as the individual episodes. Another upcoming picture book is entirely a palindrome.

What’s your hope regarding these future stories?

I hope readers, teachers, and librarians will always be able to grab one of my stories and say, “Now this one was ambitious.” Sometimes, the ambition is just to tell a perfectly polished story—what I call an “evolution on the norm.” And other times the ambition is to tell an inventive story that tries to create something new—what I call a “revolution of the form.” Evolutions or revolutions each time. I hope readers will help me stick to that.

Connect With Daniel Nayeri

What are the best ways for readers to connect with you or to follow you on social media?

I’m easy to find @DanielNayeri in the various places. I only post on Fridays, so please excuse the delay.

Website: https://www.danielnayeri.com/