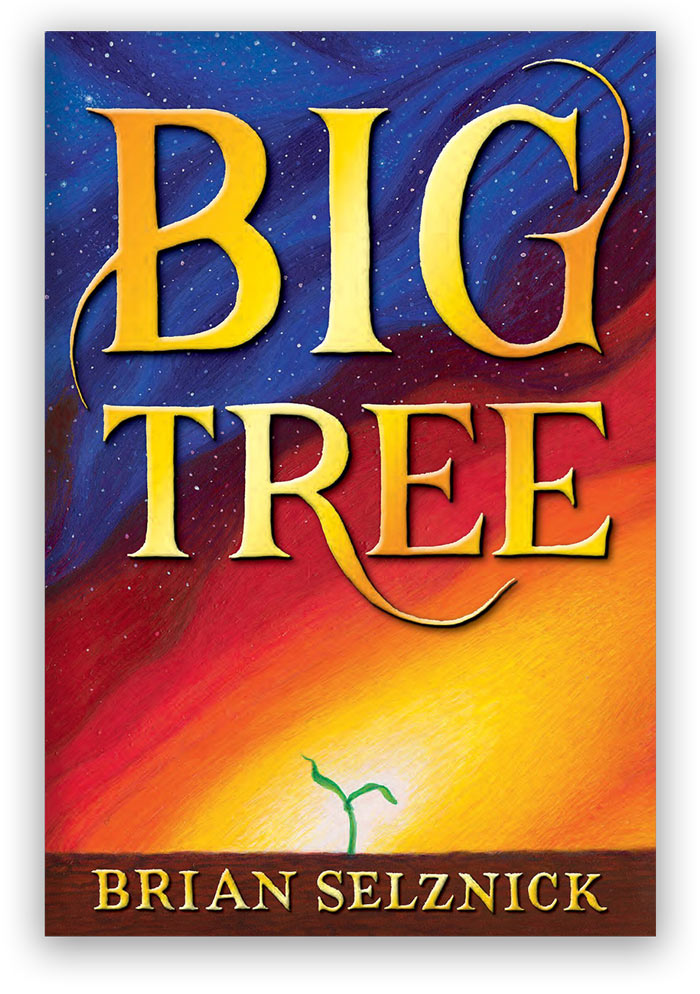

A new Brian Selznick book is always a cause for celebration, and with Big Tree (Scholastic, 2023), the Caldecott Medal-winner takes on his biggest story ever, finding inspiration in the staggering and awe-inspiring intricacies of the natural world. The adventure story of two small sycamore seeds who confront a vast and ancient realm—illuminated with nearly 300 pages of Selznick’s enthralling illustrations—is already the recipient of several starred reviews, even before its April 4th publication date.

Here, Selznick talks with Lisa Bullard about what led up to his groundbreaking new title, the process by which he creates his author-illustrated books, and some of his personal experiences with nature that helped shape the story.

I had the good fortune to see an advance copy of Big Tree! I could tell everyone who hasn’t read the book yet that it’s a story about hope, survival, community, and the endlessness of love. I could also tell them it is a big book about the smallest of things or a small book about the biggest of things. But as its creator, what would you like to tell your readers about it?

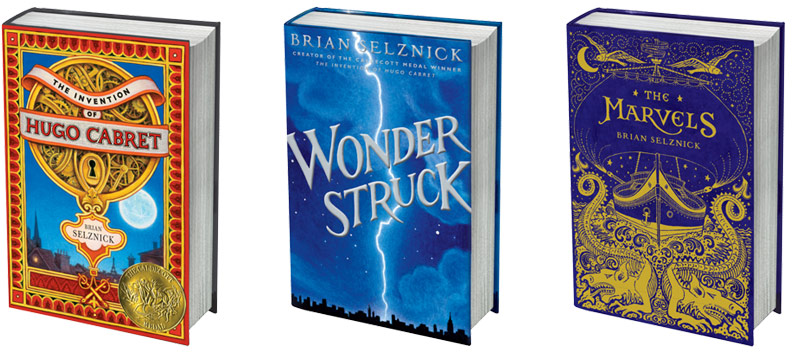

Thank you so much; I love your descriptions of the book! I am very plot-oriented when I’m writing a story, so usually when people ask what my books are about, I describe the action. For instance, I would say The Invention of Hugo Cabret (Scholastic, 2007) is a book about a boy who lives alone in a train station. But a reader I met while on tour for the book said they loved Hugo because it is about how we make our own families. I loved that and realized that’s sort of what all my books are about. Now I like to say Hugo, Wonderstruck (Scholastic, 2011), and The Marvels (Scholastic, 2015) are each about how we make our own families. So, for Big Tree, I’d probably say it’s about two tiny sycamore seeds who have to find a safe place to grow. But you are correct in saying the book is really about survival and community and love.

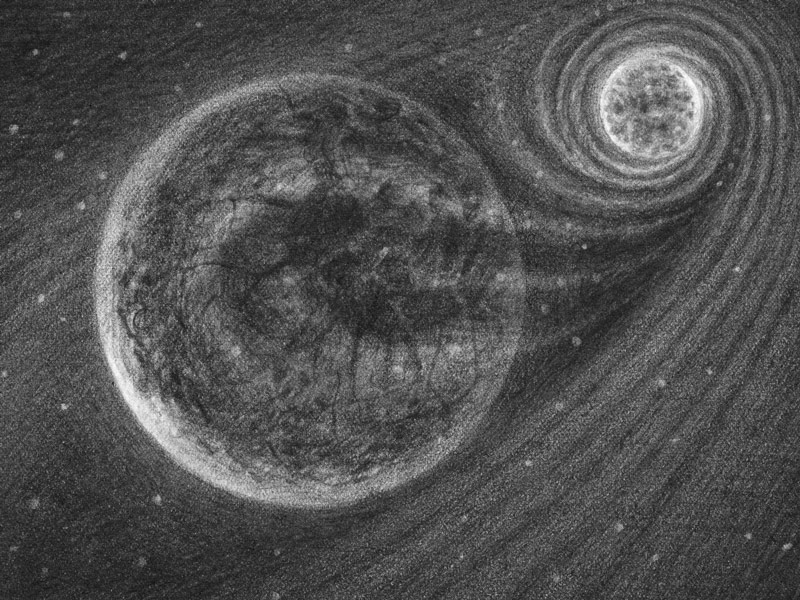

Big Tree covers a vast range of things, from dinosaurs to microscopic entities; from a heroic butterfly-like creature named Spot to the shaping of the universe; from millions of years ago to a child today. How did you decide what elements to include in the story?

Steven Spielberg had approached me with the idea to tell a story about nature from nature’s point of view. He has a deep interest in science and nature, and meeting with him and the other producer, Chris Meledandri, was incredibly fun and inspiring. Our conversations ranged from the beginning of time, to how life developed on Earth, to the ways plants communicate. I would do a huge amount of research with scientists and paleobotanists (people who study prehistoric plants), and then I’d return to Spielberg’s office filled with ideas to work into the story. I learned about the underground fungal system that allows the trees in a forest to communicate with one other (sometimes called the “Wood Wide Web”!), and tiny foraminifera, which can be found in water all over the globe and whose tiny fossils allowed us to figure out what was happening with climate change. This gave me the idea to make sure that everything in Big Tree is based on science. So, the reason Merwin and Louise can talk to each other in my story is because in real life, plants communicate (though perhaps not in English). Each time I learned something new, I figured out ways to work the science into the narrative. For instance, the “Wood Wide Web” became mushroom characters called the Ambassadors, who pop up every day to tell the trees what is going on in the forest; and the foraminifera became the Scientists, who spend their lives collecting data about the world from the water around them.

Steven Spielberg had approached me with the idea to tell a story about nature from nature’s point of view.”

What are the most powerful or moving experiences you have had while engaging with nature, and did those experiences inspire Big Tree in some way?

Growing up in suburban New Jersey, there was a small undeveloped area behind my house still covered in woodlands. I remember the awe and fear I felt as I crossed over from the edge of our lawn into the wildness of the woods. Everything changed—the sounds, the temperature, the light, the feelings. It was almost like going back in time to something more primal, and strange, and dangerous. I remember building miniature cities out of twigs and rocks and always experiencing something that felt like an escape from the everyday, civilized world.

Over time, the woods were bulldozed as more and more housing went up, and now there are only a few trees and bushes left between the yard of my childhood home and our neighbors, but I’ll never forget that feeling inside the woods. A few years ago, I also had a wonderful week living with some friends in a home in the redwood forest in Northern California. The sense of ancient history was very powerful there, and it was easy to imagine myself back in time. These memories were very helpful as I created Big Tree, which takes place at the end of the Cretaceous era. One of my goals was for the reader to connect with the forests and trees in my story so when they go out into their own backyards, or see trees and plants anywhere at all, they will have a new understanding about these magnificent and often misunderstood creatures.

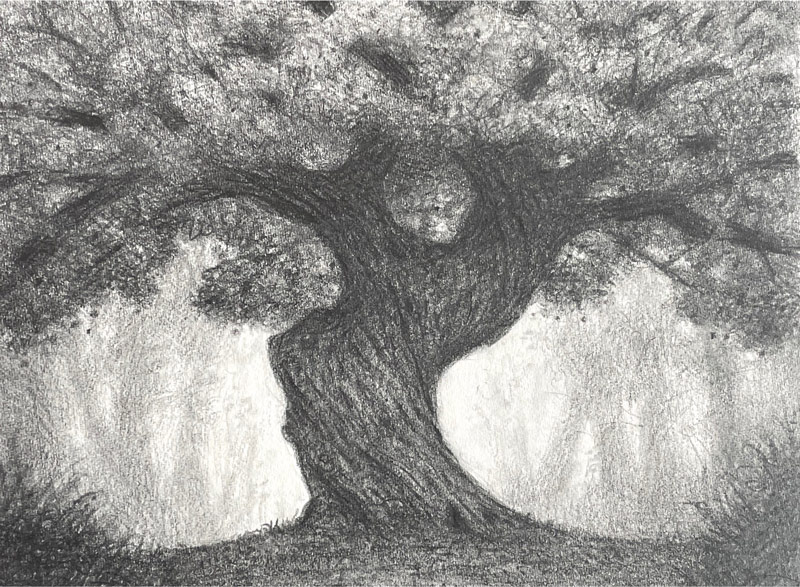

Artwork by Brian Selznick © 2023 Universal Studios.

One of my goals was for the reader to connect with the forests and trees in my story so when they go out into their own backyards, or see trees and plants anywhere at all, they will have a new understanding about these magnificent and often misunderstood creatures.”

Where do you find your characters?

It is always a little mysterious where characters come from. Since I am so plot-driven when I’m making a book, I often think of plot points before I even have characters. I will invent characters simply so they can make the plot happen! This might be a little backward from how other writers work, but it’s how my stories come to me. I usually make books about orphans or children who have been separated from their parents. I’ve never written about plants before, so I decided to make the main characters in Big Tree sycamore seeds; that way they would have some parallels with the sorts of characters I’ve created before. Merwin and Louise, like Hugo and Isabelle, Ben and Rose, and Joseph, are trying to find a safe place to grow up and a new community where they will be loved and nurtured.

Brian Selznick Talks In-Depth About His Book-Creation Process

I always start by writing, but that’s not quite accurate because I’m a visual thinker, and I actually see everything in my mind first. I never draw until I have most of the story worked out on paper (or computer). Once I have a draft of the text, I can go back and make decisions about what I want to draw and what I want to leave as words. For instance, I don’t like to have speech bubbles as in graphic novels or comics (I prefer the drawings to stand on their own), so if there is dialogue, it will appear in sections of text. But if there’s action or description, it can often be conveyed effectively through images, so I’ll remove that text and replace it with pictures.

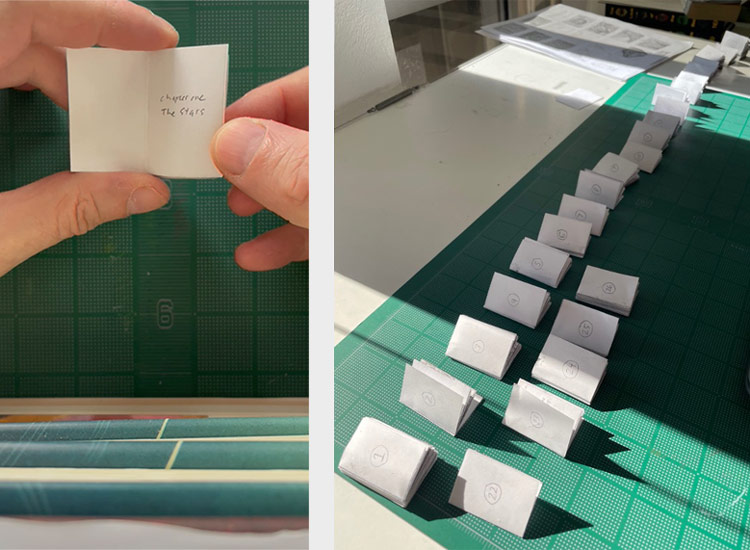

As I’m figuring all this out, I don’t draw. I make lists of what I want the drawings to be. Using Hugo as an example again, I knew that I wanted to “zoom in” on Paris at the opening of the book, so I made a list that looked like this: 1) The moon. 2) The moon over Paris. 3) A train station is now visible in the distance. 4) We see the doors of the train station where a boy is visible. 5) We see a close-up of the boy. This is Hugo.

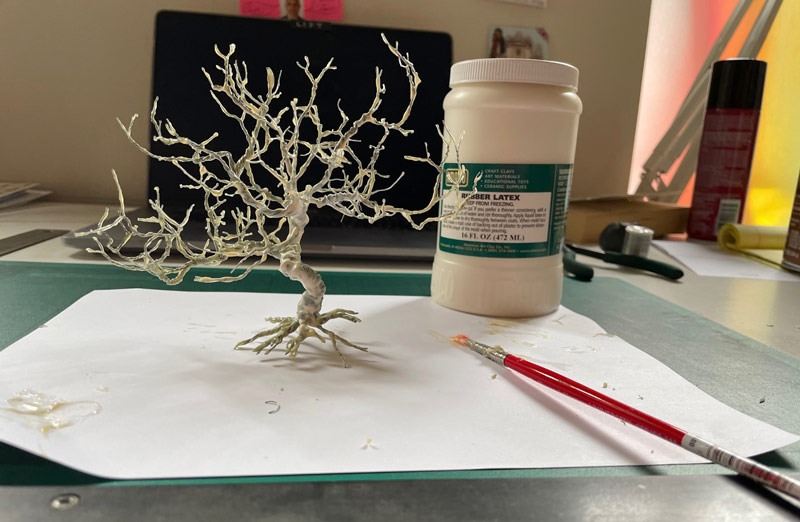

Once I have lists like this for the entire book, I draw tiny “thumbnail” sketches, Xerox them, cut them out, and glue them together, making small “dummy” books so I can turn the pages to see if the narrative is moving forward the way I’ve imagined. I adjust from there and begin doing more research, which can involve travel and photographing models. Then I do more detailed drawings until I’m ready to create the final art.

I work very small. The finished drawings are about three inches by five inches and then enlarged to the size of the book. Big Tree was unusual because it began as a screenplay for an animated movie I was writing for Steven Spielberg and Chris Meledandri, so in many ways the entire story was going to be conveyed visually. When the pandemic hit, and it became clear the movie was never going to happen, I proposed to Mr. Spielberg and Mr. Meledandri that I make the story into an illustrated book. The challenge was to then figure out which parts of the story would work best as drawings and which parts would work best as text.

A young Brian Selznick

Merwin is a loyal, loving worrier who wants to do the right thing but who often misjudges what that is. Louise is brave and questing, a “bright light” who wants to save the world. Were you like either of them as a child?

I don’t know if I was like Merwin or Louise as a kid, but I often realize when I’m finished with a story that I’m sort of like all the characters in one way or another. Sometimes I give characters my own traits on purpose, but often it’s unconscious. Parts of me are like Hugo, who often feels like he doesn’t belong anywhere. He has a special talent, fixing machines, while my special talent as a kid was drawing. But I’m also sort of like Georges Melies, the mean old man in the toy booth. I’m not that old, and I hope I’m not too mean, but sometimes I relate to his sadness and frustration. In Big Tree, Merwin can be very rigid; can be sure his ideas are one hundred percent correct, and it causes him much grief. That’s something I can relate to, but I can also relate to Louise, who is dreamy and a little strange, guided by visions she doesn’t always understand.

What is the best advice you have for the educators and librarians who work with young writers and artists?

If you are an educator or a librarian, I’m guessing (if you’re reading this) you’re already the type of person who wants to encourage your students, but it’s always helpful to be reminded how powerful your support and approval can be. The simple act of offering approval can be life changing to a young person. After I graduated college, I worked for a few years as a bookseller at Eeyore’s Books for Children, an independent bookstore in New York City. The thrill of giving the right book to the right child, seeing their face light up, and having them return after finishing it and wanting more, was really the best feeling in the world.

The thrill of giving the right book to the right child, seeing their face light up, and having them return after finishing it and wanting more, was really the best feeling in the world.”

How about the best advice you have for young writers and/or young artists?

For young writers and artists, I would say the best thing to do is to write and draw as much as you can. Write what you want to write and draw pictures of things you love. I know it’s hard, but it’s best not to worry about what other people say and just follow your interests. Also, if you want to be a writer, read as many books as you can. Even bad books can teach you things! And if you like to draw, look at the work of other artists. Visit museums if you can or look up great museums online and explore their collections. You never know where you might find inspiration. Go to your local library or your school library and ask for help. Librarians can guide you to all sorts of things you might never find on your own.

Would you like to share anything with your fans about other upcoming books?

I’m working on a new book now that in many ways is unlike anything else I’ve written before, but that’s always the goal, isn’t it? To do something that’s new to you, and unexpected. That’s where the challenge is and why I love my job so much. I’m also working on some stage and film adaptations of my books, and it’s really exciting to see my stories transform into a new medium.

Connect With Brian Selznick

What are the best ways for readers to connect with you?

I have a website with information about all my books and other projects: thebrianselznick.com. I’m going on a big tour for Big Tree, and you’ll find the schedule there. Maybe I’m coming to a city near you!

Is there anything else you’d like to add?

To all the teachers and librarians reading this, thank you so much for the work you do, and for bringing my work and the work of my colleagues into your classrooms and libraries. I’m very proud to be part of this big ecosystem where stories connect people to one another all over the world.