Joanna Ho’s first book for young people, Eyes That Kiss in the Corners (HarperCollins, 2021), came out just over a year ago and it catapulted her to the New York Times Best-Seller List along with a host of “Best Books of 2021” lists. In the months since, two more picture books have only added to her critical acclaim. But for Ho, writing is about more than garnering awards—it is an important way to share her passion for anti-bias, anti-racism, and equity work.

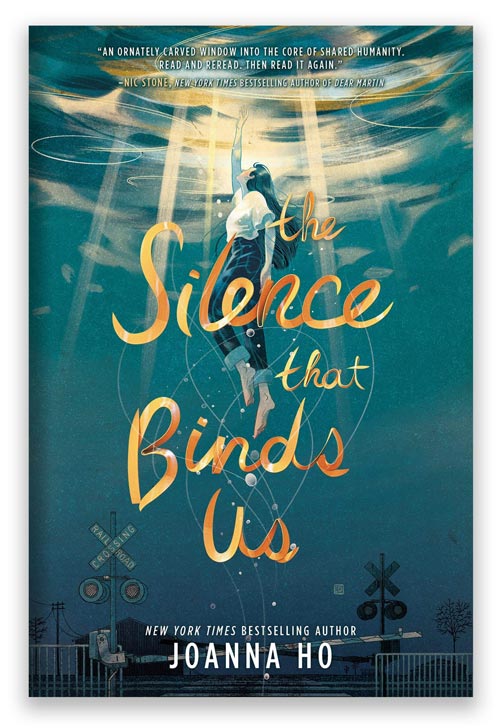

This June, Ho debuts her young adult novel, The Silence That Binds Us (HarperTeen, 2022). In the book, sixteen-year-old Asian American Maybelline Chen feels invisible next to her popular older brother, Danny, in her parents’ eyes, especially when he gets into Princeton. But when Danny’s secret struggle with depression leads to suicide, May is devastated. After his death, May’s family faces racist accusations faulting them for Danny’s death. Although her parents just want to ignore the insults, May fights back through her writing with unexpected consequences.

Here, Lisa Bullard talks with Ho about the inspiration for this YA book, the importance of speaking out, and how she continues to find hope in young people.

Will you share some details about the things that influenced and shaped this YA novel?

I started the story that would become this book in the summer of 2017. It was born from the desire to tell a story about anti-Asian racism. I wanted the world to know it was real. I wanted to explore Asian American history, Black and Asian solidarity, the reasons we stay silent, and what it takes to speak out.

Never, not once, in the years that it took to imagine, draft, and revise this novel, did I imagine that the term “anti-Asian racism” would become a phrase widely used in newspaper headlines, social media posts, or in any kind of collective dialogue. I never imagined a global pandemic. Atlanta. Attacks on our elderly. I could not have fathomed that one day, anything related to Asians in America would become a topic of collective conversation. It had simply never happened at that scale in the decades I have breathed on this planet.

This story was born from the teenage suicide epidemic that racked my community for years, the effects of which still reverberate to this day. It was born from a group dinner I attended where a wealthy white man stated that the pressure and stress and suicides in our community come from the Asian families that live here. It was born from a Lyft driver who told me the same thing less than a week later. It was born from the invisibility of being Asian. It is an invisibility that runs so deep, people don’t see me even when I face them across a dinner table, or when I’m the only passenger in their car.

What would it be like to have your world shattered at the suicide of a son, a brother, a friend—and then have the world accuse you of driving your loved one to his own death?

I set out to write a book to explore this question. It started out as a story about anti-Asian racism, but racism doesn’t exist in a vacuum. This is a story about family, friendship, mental health, fear, power, hope, healing, and love. It is a little bit of my truth. It is one of many stories that can and must be told.

It started out as a story about anti-Asian racism, but racism doesn’t exist in a vacuum.”

One of your teenage characters says, “We will never have a better world until all our stories are told. We will never have a better world until all our histories are known. We will never have a better world until all our voices are heard.” Tell us a bit more about how those themes infuse this novel.

For too long, the narratives we have been taught—the histories, the stories, the pervasive understandings of people—have been tightly controlled and told to glorify a dominant, white-centered framing of truth. This can be expanded to be straight, cis, white, able-bodied, etc. We have seen in the recent news how blatantly and actively some people are trying to perpetuate this twisted perspective of truth through controlling curriculum and banning books. Asian stories, the history of Asians in America, the diverse and differing realities of Asians, have been made all but invisible. This invisibility has a damaging impact on our racial dialogue, our identity development, our ability to build coalitions and solidarity with others. And we are but one of many groups who have been rendered silent and pushed to the side. This novel seeks to explore what it takes to change these dominant narratives in one community. There is a cost that comes from speaking out, and there is a cost that comes from staying silent. How do we know the right path forward if every choice requires sacrifice?

Along with being a bestselling author, you’re also an educator—currently the vice principal of a high school, and previously (among other educational roles) an English teacher. How can educators help students to speak out?

Listen to your students. Build in structures in your classroom and school to listen to and learn from students. Make time to sit down and interview them individually, create student panels, do Kiva Protocols. Invite students into your staff meetings to share. Do community circles in classrooms. Students have so much to say, and when they know that what they say can make an impact, it will empower them to continue speaking up—and it will make our schools better too!

Students have so much to say, and when they know that what they say can make an impact, it will empower them to continue speaking up—and it will make our schools better too!”

In The Silence That Binds Us, your teenage main character, May, finds a variety of ways to share her voice: prose, poetry, and text messages. Did you know from the beginning that you wanted to include that mix, or did it evolve through the writing and revision process?

It isn’t something I planned specifically, but it seemed to flow out that way as I wrote. The texting and poetry felt in line with May’s character and provided different ways to better understand her relationships and her heart.

What opportunities and challenges did you discover in writing The Silence That Binds Us?

The act of storytelling is an act of love. It is also an act of bravery. Not just in the creating of the story, but in the sharing of it too. I have loved learning so much more of my own history in this country as I researched for this book. It has brought me closer to my own family and highlighted how much I didn’t know and still have to learn. The journey of writing and revising this story has forced me to understand my own communities more deeply.

It is a tremendous privilege to be able to write for young people; to connect with others through the words I put on a page. There is also a tremendous responsibility that comes with this privilege. The challenge is letting go enough to allow readers to interpret the story through their own lenses. It’s hard not to be engaged in continuing dialogue with those who read my books. I am learning to love and appreciate the ways others breathe their own lives into the stories I write.

The act of storytelling is an act of love. It is also an act of bravery. Not just in the creating of the story, but in the sharing of it too.”

Your character May is a writer. Do you have advice for young people who are also interested in becoming writers?

To the young people interested in becoming writers I would say: 1) Read a lot and read widely. 2) Write regularly and hone your craft. See #1. It’s one of the best ways to get better as a writer. 3) Be persistent, stubborn even, in the pursuit of this dream. It’s a long and winding road, but you can do it if you stay the course. 4) There are stories only you can tell. Write those stories. They matter. The world needs them.

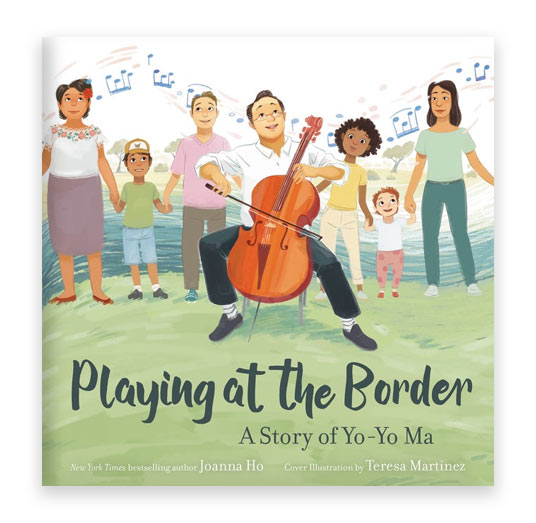

Your earlier titles—Eyes That Kiss in the Corners, Eyes That Speak to the Stars (HarperCollins, 2022), and the picture book biography Playing at the Border: A Story of Yo-Yo Ma (HarperCollins, 2021)—have already established you as a strong picture book voice. Did you have to change your approach to writing when it came to a YA novel?

In some ways, writing a YA novel is very different than writing a picture book. Just the word count alone will show this; my picture books tend to be between 400 to 600 words, and this novel is close to 90,000! But the principles of storytelling are the same. It was fun and challenging in the best ways to explore a new age group. There was so much freedom to play on the page, not only with voice and style, but with content and complexity as well.

Do you have plans to write for other age levels as well?

Writing is a constant exploration and process of growth. I’d love to continue pushing my own craft, expanding my own toolbox, by writing across various genres and age groups. There are still so many ways to experiment, and I’m just getting started!

What are your thoughts about using picture books in classrooms with older students?

Picture books are incredibly layered and complex. Every single word has a purpose, and those words are often chosen with deep intentionality and nuance. Additionally, the interconnectedness of text and illustration offers additional layers of story. For example, in Eyes That Kiss in the Corners and Eyes That Speak to the Stars, there are phrases, words, and illustrations that explore white supremacist systems that reinforce white beauty standards, specific colors that reclaim terms used to oppress Asians in the U.S., microaggressions, cultural symbols of power and rebirth, etc. Or you could just read the books as stories of familial love and self-empowerment.

Similarly, Playing at the Border can be read as a sweet book about building bridges across cultures. Or you could dive into the language and images, and do deep analysis of the history and immigration policies this book was specifically written to disrupt.

Picture books are incredible tools for teaching because they offer complexity that invites analysis and discourse across all ages.

How does working with young people on a day-to-day basis affect your writing?

My experience as an educator shows me daily the brilliance of young people. They give me hope and never cease to inspire me with their passion and perseverance. They see and dissect everything. This understanding gives me the freedom to write truthfully to all ages—our stories must match the wisdom of our youth.

My experience as an educator shows me daily the brilliance of young people; they give me hope and never cease to inspire me with their passion and perseverance.”

What are the best ways for readers to connect with you or follow you on social media?

I’m @joannahowrites on IG, Twitter, and Facebook. My website is joannahowrites.com.