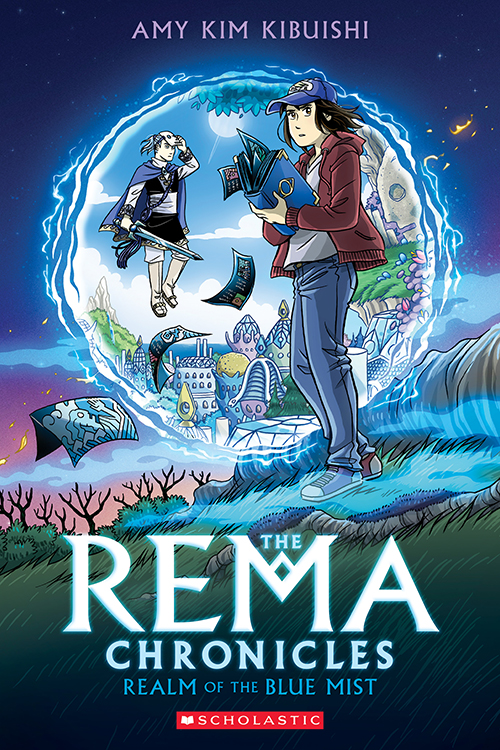

The ability to dream up worlds in one’s mind is crucial for creating an immersive experience for readers. In today’s guest post on the Mackin Community Blog, Amy Kim Kibuishi, creator of the middle-grade graphic novel series The Rema Chronicles, shares how she draws inspiration from real-life travels, and uses them to enrich the fantasy worlds she creates.

My favorite fantasy worlds tend to feel like they were sourced from real, lived experiences. The surreal sameness of Camazotz from A Wrinkle in Time, the moors of Middle Earth in Lord of the Rings, and even the tiny library in the rose bush from Mrs. Frisby and the Rats of NIMH all feel like places the authors have seen and then embellished upon. Curiosity and a general love for the real world, I think, are the most important ingredients for building a good fantasy world.

When I was 14, my mother took me to visit family in South Korea. It was the first time I had ever left upstate New York. We spent a whole month between Seoul and my mother’s hometown of Chumunjin—what was then a small fishing town nestled between tall mountains and a cerulean sea—and I soaked in every minute.

When I was 14, my mother took me to visit family in South Korea. It was the first time I had ever left upstate New York. We spent a whole month between Seoul and my mother’s hometown of Chumunjin—what was then a small fishing town nestled between tall mountains and a cerulean sea—and I soaked in every minute.

I had so many questions: Why was grandpa’s grave the shape of a small grassy hill, and why did grandma pour a can of Coke on it? How did my eight-year-old cousin get the skills to catch a dragonfly between her fingers? How can I take a bath using only a bowl of water, and what do I do with the bullfrog that came into the bathroom through the pipe? Also, how many times has my mother plucked a sea cucumber right from the ocean and ate it, and do all people in Chumunjin really have fish stew with a side of fish eggs for breakfast every morning?

That same curiosity I had for Chumunjin’s fishing culture is what I tap into when I work on worldbuilding for The Rema Chronicles. If you already ask questions about a beloved place in the real world, it’s easy to transfer those questions to your fantasy world.

For example, what is the geography of the place? Do they have seasons? What sort of clothes do they wear? Then, to go deeper, how do the clothes function and are they comfortable if you wore them? What sort of holidays do they celebrate in your world, and what food is served? How is the food eaten, prepared, and harvested? How is it stored? How do they bathe in your world, and what do you do with the biffwhiff that came into the bathroom through the pipe? How many times has your character plucked a noomble right from the ocean and ate it, and do all people in Terell really have noomble stew with a side of noomble eggs for breakfast every morning? Once you start collecting answers for these kinds of questions, over time the world starts to feel like a real place.

My biggest worldbuilding challenge was developing the mythology of The Rema Chronicles, a central element to the story. I wanted a way to show how religious thinking, regardless of the mythos, can inspire beauty and culture. I wanted to also show how it can corrupt people and be used against them. So, I had to ask myself how do the people of Rema think the world began? What forces changed the story to fit their needs? How can I make it feel like a living myth, at least in the context of the characters and their world? Once I had the mythology, I could start doing the next step: visually designing the world for comics.

Visual design, like writing, is a set of choices based on personal taste, life experience, and skill. When it comes to comics and fantasy, I like to treat the setting like a character of its own. It is the arena in which the story is played out, and it has a voice. That voice will establish the overall mood of the reading experience, so it’s well worth developing.

I knew I wanted Rema to pay homage to my Korean roots, so I indulged in books of Korean art and traditional Korean clothing. I collected folders of inspirational photographs of Chumunjin from the internet and meditated on my time spent there. I wanted Cerey, the city where the story takes place, to feel like Chumunjin: a beautiful seaside town nestled between tall mountains and a cerulean sea.

Just as the town of Chumunjin circa 1994 had a functional, architectural, and visual language—blue pagodas, terra-cotta rooftops, and rice-paper wooden doors—I looked for ways to have the symbols of the Reman gods steeped into architecture, flags, and jewelry, to give Cerey its own visual identity as a city.

I also thought about transportation. How did Remans primarily get around? Well, they flew like superheroes, of course! At least most of them did, although it could be exhausting. Therefore, I peppered the Reman landscape with white-column resting platforms and had the buildings host numerous balconies.

Other details accumulated: the wealthier, more powerful classes lived in elevated houses, inaccessible to those who walked on the ground, and many buildings were tall, winding towers easy to ascend for fliers. Of course, clumsy staircases were added for those who couldn’t fly so well, as an afterthought.

All of these elements and more were collected as I developed Rema and its cities, but in the space of a graphic novel, there is not enough room to discuss it all. And there doesn’t have to be. The details exist in the background, just as the details of traveling to another country exist in the background for the traveler. There is no way one could possibly understand why or how everything got there while passing through a place, but it’s there, and it gives the impression of a living, breathing world begging to be explored.

I believe if an artist puts as much effort into the development of their fantasy world as they do their characters, the reader will be transported. And hopefully, when the reader closes the book, they will look to our world with a little more curiosity, and a little more love.