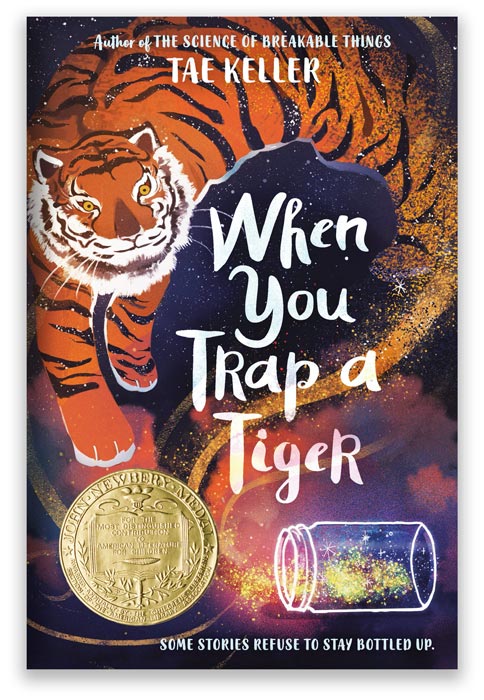

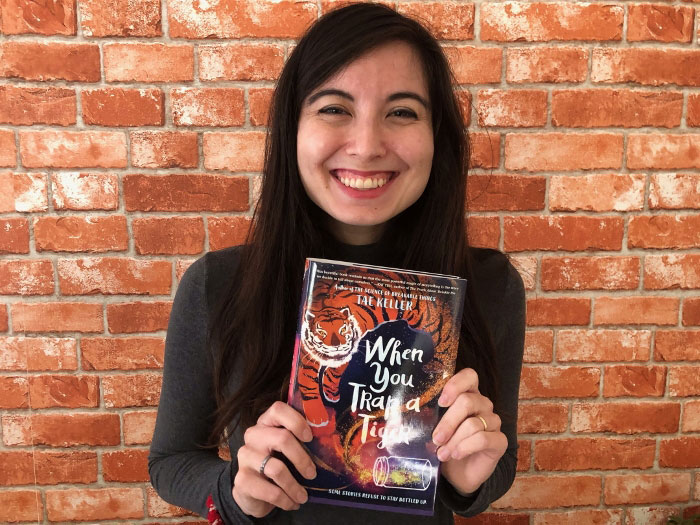

The central question of Tae Keller’s 2021 Newbery Medal acceptance speech is, “Why do we tell stories?” In that speech, she shares how stories form a connection to her family and heritage, bridging the gap between Korea and Hawaii, and how stories also bridge the gap between individual human beings. When You Trap a Tiger (Random House, 2020), the book for which Keller won the Newbery Medal, is at its heart a story about stories; it pulses with their power. And Keller’s belief in the potency of stories is reinforced over and over again in what she shares with her readers and followers.

Here, Lisa Bullard talks with Keller about why she believes stories hold so much power, the impact of winning the Newbery, and some tantalizing details about her upcoming middle grade novel due out in summer of 2022.

Stories infuse so much of your books and the other pieces that you share with your readers and the world. Can you talk a little about the power of stories and what they have meant in your own life?

Stories help us ask and navigate the big, scary questions in our lives. How do we find our place in the world? How do we support and care for the people we love? And a pressing question in almost all middle grade books: how do we bridge the gap between childhood and adulthood? Stories are a safe space to explore these ideas, and in my own life, I have always turned to them for hope and reassurance.

Stories help us ask and navigate the big, scary questions in our lives.”

In your 2021 Newbery acceptance speech you say, “When You Trap a Tiger opens with Lily saying, ‘I can turn invisible.’ When I wrote that, I was drawing on my own experience.” I imagine that winning a Newbery means that you have lost that ability to “turn invisible” because of the attention that the award brings. Does this kind of success make things easier or harder for a writer?

In some practical ways, it’s easier. Writing is so often an uncertain career. I spent the first four years wondering how long I could make it work, unsure if there’d be another book contract, feeling like this job was a wonderful, but temporary, thing. The success of When You Trap a Tiger has given me some sense of security. I can think of myself as a writer now, instead of a “writer for now.” That’s an unbelievable gift, and I’m hugely grateful for it.

In other ways, of course, it’s harder. I’m nervous about what people will think about my next book! I never want to disappoint readers. And then there are the ways in which my writing life isn’t harder or easier—a lot has stayed the same. I still sit down at the same desk. I still love my job most days, and struggle with plot points and character beats other days. Really, the story doesn’t care about success; it just needs me to sit down and keep showing up.

Through your characters, you put us inside the heads of individuals who are navigating what it means to have a biracial identity. Has writing these characters helped you shape your story?

I think writing books about biracial characters has helped me feel okay with not having shape to the story of my identity. I’ve become more comfortable with the knowledge that my experiences and feelings about culture and heritage are way too big to fit into a single story. Now that I have multiple books about biracial characters, I feel some freedom to explore different emotions and perspectives on identity—all of which I relate to or have had at some point in my life. It’s given me space, I suppose. That expansiveness of identity is also why I encourage people to read multiple stories when they’re trying to understand a particular perspective—and not just stories by one author, but stories by many authors.

I’ve become more comfortable with the knowledge that my experiences and feelings about culture and heritage are way too big to fit into a single story.”

The materials you offer on your website include a “Mythology Guide” where you address some of the ways you’ve adapted, questioned, and built off of traditional Korean tales for When You Trap a Tiger. What suggestions do you have for your readers based on your own experiences with exploring these traditional stories?

I learned so much in my research for When You Trap a Tiger, and reading folklore and history has taught me so much about my family and myself. I would very much encourage readers to do the same with their cultural stories! And perhaps more than anything, I’d encourage them to ask an older relative or loved one to share some of their personal stories. I learned so much from my halmoni [grandmother in Korean] as I wrote this book, and weaving her personal life into my beloved folktales was a great honor.

Rice cakes play a starring role in When You Trap a Tiger. Why do you think it is that food so often has emotional resonance for us?

For me, food is like a bridge through time. With certain dishes—and especially with specific family recipes—I can imagine my parents, grandparents, and ancestors eating the same thing at different points in their lives. There’s something immensely comforting about that.

Because of the scene in the book, I also must ask if you’ve actually made rice cakes with grape jelly instead of bean paste?

I have not made rice cakes with grape jelly—but I have made many, many batches that haven’t turned out exactly as expected. I learned the hard way that they can still be good even if they aren’t perfect!

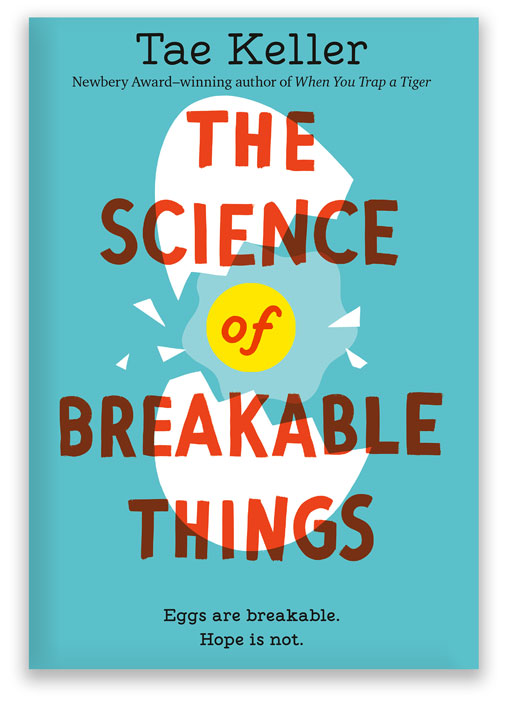

You share stories back and forth with readers through your monthly newsletter, which you call “A Love Letter.” One of those stories is your first memory, the hilarious tale about the time your mother ate your imaginary dog, a memory rooted in both creation and loss. Do you perceive those two themes as also shaping When You Trap a Tiger and your previous novel, The Science of Breakable Things (Random House, 2018)?

I’m always interested in the intersection of hope and heartache, of bitter and sweet, so it’s interesting that you mention creation and loss. I think I’m always drawn to those strong conflicting emotions, because I think that’s such a wonderful human thing, the way we can hold contradictory feelings in our hearts. And maybe that’s a through line between all of my books—exploring, acknowledging, and celebrating the vast range of emotional experience, and letting yourself feel it all.

You write for middle grade readers—a time in life in which young people are trying to figure out how to “create” themselves. What draws you to this age level?

Middle school is such a fascinating in-between space—stuck somewhere between being a kid and being a teenager. When I was in middle school, I remember feeling, for the first time, like I was part of the bigger world, and I had no idea where I fit inside it. That’s a deeply vulnerable place to be, and I write as a way to tell those kids—and to tell my own middle school self—that they are going to be okay. They are going to make their way, and they don’t have to do it alone.

I write as a way to tell [middle school] kids—and to tell my own middle school self—that they are going to be okay. They are going to make their way, and they don’t have to do it alone.”

I know readers will be thrilled to hear that you have a new middle grade novel coming out in summer 2022, called Jennifer Chan Is Not Alone (Random House, 2022). What can you tell us about it?

I’m excited about this book! All my books are personal, but this one speaks most to who I was and the experiences I had in middle school.

Here’s the quick pitch: When eccentric Jennifer Chan disappears, her former friend, Mallory, goes looking for her, wondering guiltily whether Jennifer was driven away by bullying classmates, or whether she really could’ve found the aliens she hunted. It’s about isolation, redemption, and forgiveness. It’s a story about feeling alienated while searching for aliens.

Aliens and UFOs have captured the literary imagination for decades. What inspired you to bring them into this story?

The simple answer is that I think aliens are fun—which sounds flip, but isn’t quite. Some of the bullying scenes are emotionally heavy, and I wanted something lighter to balance that out and drive the plot. Aliens also provided such a rich thematic ground for me to explore ideas about uncertainty, belief, hope, and what we consider strange, weird, or “alien.”

What conversations do you hope the book will inspire?

Oh dear, this question makes me realize that I’ll get asked what the aliens mean, the same way I get asked about the tiger in When You Trap a Tiger! And I’ll have to give the same response to both, which is that I’m not the one who can answer that. Once a reader finds this book, the meaning belongs to them. Hopefully, the aliens will represent something larger for them, and it’s not my place to tell them whether their interpretation is right or wrong.

I do hope, though, that the book sparks conversations about belief—in ourselves, in others, in the unknown. And I hope it inspires conversations about what it means to be a good person, and how to be a good person.

Once a reader finds this book, the meaning belongs to them.”

What are the best ways for readers to connect with you or to follow you on social media?

I’m on Twitter (@taekeller) and Instagram (@tae_keller). I also write email love letters, which I try to send out at least once a season. You can find those here: bit.ly/lovetae.