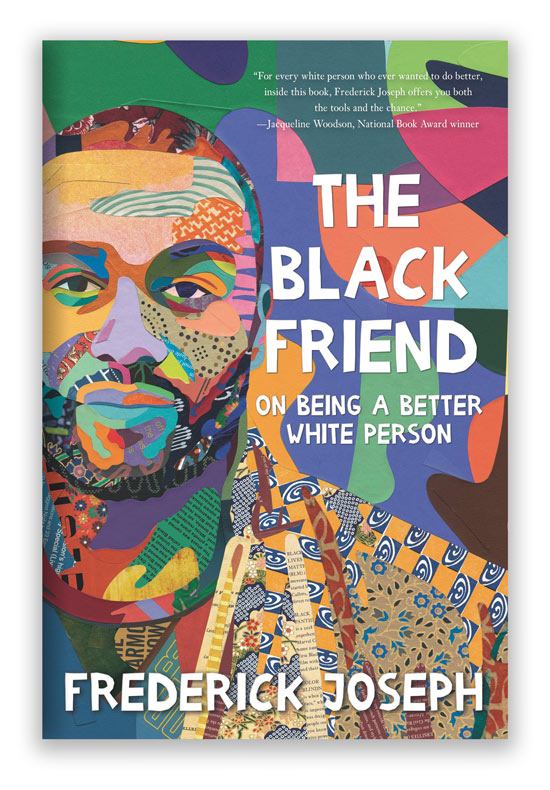

In his preface to The Black Friend: On Being a Better White Person (Candlewick Press, 2020)—the winner of the International Literacy Association 2021 Award for Young Adult Nonfiction— Frederick Joseph is clear about his goals: “My hope is that this book will be a tool to help others see and understand the obvious and not-so-obvious ways in which racism and white supremacy not only have infected our society but are actually the foundation of it. That it might spark the flame in someone who one day helps burn down the historic oppression we have faced.” Throughout the pages that follow, he shares his personal experiences with racism—friend to friend—in a way that invites young adult readers to take a much deeper look at a topic that is often tough to talk about, but also essential to true change.

As school librarian Clare Wilkins says on the Reading Zone website, “This book has been described as a ‘conversation-starter’ and I think that is an ideal description. It’s a passionate and timely introduction to a topic that the YA audience is increasingly aware of and engaged in.”

Here, Lisa Bullard talks with Joseph not only about changing attitudes, but about taking the actions that actually change lives.

The Black Friend is listed for ages 12 and up. What is it about readers of that age that made you decide to target a young adult audience?

I didn’t set out to write a book for young adults, but it was one of the best decisions I’ve ever made. The idea originally came from my agent, Alex Slater. He thought that my voice would make the most impact if we made it accessible to young people, which I loved the thought of. I think there is a misconception that we can’t have certain important conversations with young people, when in fact, they are the most important people to be having them with.

I think there is a misconception that we can’t have certain important conversations with young people, when in fact, they are the most important people to be having them with.”

The San Francisco Chronicle’s review describes the book as “bristling with righteous indignation but tempered by enduring hope.” It strikes me that they could have been describing you as well, at least the “you” who wrote the book.

I think that’s pretty on point. One of my idols, James Baldwin, once said, “To be a Negro in this country and to be relatively conscious is to be in a rage almost all the time.” I think that quote sums me up well. I am disappointed, frustrated, and hurt by the things that I see happening, which are simply manifestations of things that began long before I was here. But I also have hope that things may continue to change. Without that hope, there would be no point in me writing.

Throughout the book, you invite numerous powerful voices—such as Angie Thomas, author of The Hate U Give—to share their own insights on racism, white supremacy, and the other critical topics you tackle. Why was it important to you to include those other voices?

I felt it was important to include those perspectives because racism, like other forms of oppression, is intersectional. I have experienced racism and I have studied racism, but at the end of the day I only live in my body and have my experiences. I can’t speak from the perspective of a Black woman, a Chicano, a Southeast Asian woman, etc. So why not invite them to take part in the conversation? I wanted that book to help change lives, which meant it was best to not simply exist as an echo chamber of my own thoughts and experiences.

Educators and librarians will want to seek out the Candlewick Press Teacher’s Guide for the book, prepared by Dr. Sonja Cherry-Paul, educator, author, and the cofounder of the Institute for Racial Equity in Literacy. Beyond the great wealth of material in the guide, do you have other suggestions for educators who want to use the book in their classrooms?

My suggestion for educators is to simply let the book facilitate honest dialogue with and amongst students. The book is a conversation starter and a thought sparker, so I would hope educators and librarians will fan those flames however they can.

The book is a conversation starter and a thought sparker, so I would hope educators and librarians will fan those flames however they can.”

In the preface, you note that you finished writing the book in 2019. So much has happened since then. Is there anything you’d like to add based on the past couple of years?

If I could add anything, it would be a note about the regression and complicit nature of progress in some spaces. I think with the murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and countless others, many people became involved with the Black Lives Matter movement and moment. But the issue was just that—for so many it was just a moment—and support has tapered off to levels lower than even what we saw before the summer of 2020, based on what I’ve read.

That idea—that white people must make this more than just a “moment”—comes through loud and clear, especially with chapter headings such as “In the End: We Don’t Need Allies; We Need Accomplices.” Do you have any particular advice for educators and librarians who are committed to becoming accomplices?

My advice to educators and librarians who want to be accomplices is to create safe spaces and honest spaces. Students from all walks of life are dealing with things we can’t imagine, from navigating racism to cultivating identity as it pertains to sexuality and gender. Those students rely on you not to just want to be better, but to help protect them. There is always a way that educators and librarians can create spaces where students feel they are safe and appreciated, which can be life changing. It’s something I wish I had.

There is always a way that educators and librarians can create spaces where students feel they are safe and appreciated, which can be life changing.”

Has having the book in the world changed anything for you?

As far as how things have or haven’t changed for me, I think things are relatively the same. But the release and success of The Black Friend has given me a larger platform and the opportunity to figure out how to strategically use my voice and writing to create far more change.

What are you hearing back from readers? Has any of the feedback moved you in a special way?

I love hearing from readers if they have something positive to say. I read enough reviews of the book from critics and death threats from people who despise my work. My interest is in how the book has helped people, quite frankly. Which brings to mind a young Chicana who attended a Zoom I hosted to discuss the book. She thanked me for writing the book because she said it was the first time many of her classmates had “seen her” as the only non-white student in class. That’s the feedback I’m interested in, the kinds of things that remind me to keep going.

Do you have plans to write other titles for younger readers?

I actually have two books coming out in 2022, one of which is for younger readers! The book is called Better Than We Found It, which will be published by Candlewick Press and co-authored by my brilliant fiancée, Porsche Landon. That book is a huge undertaking, as we are tackling issues such as climate change, gun violence, and gender binaries, which is why we’ve invited brilliant minds such as Senator Elizabeth Warren, Chelsea Clinton, and Nic Stone to lend us their perspective on certain topics.

What are the best ways for readers to follow you on social media?

I am very active on Instagram and Twitter and can be found at @FredTJoseph.

Is there anything else you’d like to add?

I’d like to add something I was thinking about the other day. No one started where you see them today. Your favorite writer, activist, celebrity, and so on. Whether you’re pursuing a dream or trying to be a more progressive and open-minded person, it’s all about steps and action. Which I think is what makes The Black Friend special. I’m not asking for perfection; I’m asking for steps and action.