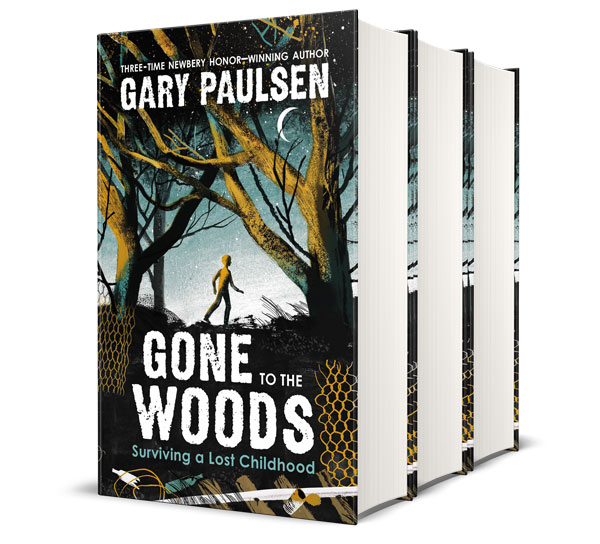

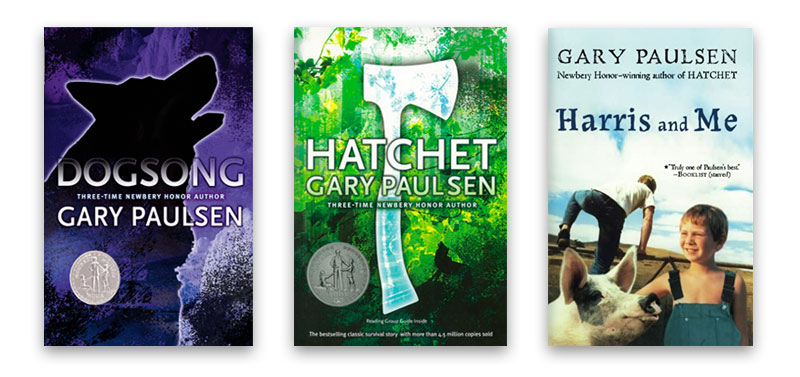

Renowned author Gary Paulsen’s riveting new memoir, Gone to the Woods: Surviving a Lost Childhood, is as much a survival story as any of his well-known wilderness adventures. And it adds new dimensions to titles that have become beloved classroom classics—books such as Hatchet, Dogsong, and Harris and Me. Here, Paulsen talks with Lisa Bullard about his memoir while offering his heartfelt thanks to all the people who put books into the hands of kids.

How did this memoir come to be?

Initially, I had thought Gone to the Woods would be three shorter books. I’ve written about my childhood over the years, bits and pieces here and there, but there were several points of time from when I was young that I’d not written about yet. My agent, and then my editor, suggested that I tie thethree manuscripts together … to make one book that presented the missing pieces of my childhood, the pivotal moments when life changed for me.

You refer to yourself throughout as “the boy.” Why did you choose to tell your story this way?

It turned out I could be more honest in third person. There’s always the tendency in first person tomake it nicer than it was, to show yourself in a better light, but I could be more truthful and tell a better story for “the boy” than I could for “me” or “I.” And I actually found myself thinking, as I was re-reading the manuscript, “I hope the little bugger will be okay.”

Gary Paulsen shares some favorite anecdotes about his readers:

One of my favorite stories happened a while back. A kid had been on a camping trip with his school and gotten separated from the group and lost in the wilderness. There was a big search for him, and they interviewed his dad on TV. The dad, he was so cool, he said, “You know, I’m not as worried as I should be because we’ve read Hatchet several times together, so I’m sure he knows to find shelter and water.” He was later found safe and sound. And another story, that is forever etched on my heart, is when a man handed a letter to a friend of mine at a conference. He had been illiterate his whole life and had only recently learned to read using my books. He said this was the second letter he ever wrote, and that the first letter had been to his son, telling him he could read now and recommending my books.

Recently, to mark the publication of Gone to the Woods, my publisher put together a Zoom call with a bunch of teachers and librarians and booksellers who shared their personal stories of reading, teaching, booktalking, and selling my books over the years. I think I held it together pretty well when I was on screen with them listening to them talk, but I’d be lying if I said I didn’t cry when it was all over. They were just so sweet and they work so hard. It made me furious all over again that teachers and librarians have no funding and have to spend their own money in many cases to get books on the shelves of their classrooms.

Your writing is very honest, even raw at times. Did you feel the need to omit anything because of your young readers?

I tried to write as honestly as I could because that’s what readers—what children—deserve, and I want to tell them (because I wish someone had told me), “It gets better, it does get better. You will survive this.” I never feel like I need to omit, or water down, or sugarcoat anything for young readers, but sometimes my agent or editor or copyeditor will flag a passage or some language that they feel teachers, librarians, or parents might object to, which would prevent the book from getting into the hands of young people. I don’t like that, and I wish it didn’t happen, but I understand. Even so, I give young people a lot of credit for reading between the lines, and for understanding what I’m talking about.

“I tried to write as honestly as I could because that’s what readers—what children—deserve, and I want to tell them (because I wish someone had told me), ‘It gets better, it does get better. You will survive this.’”

One section of the book is titled “Thirteen,” which was the age the town librarian presented you with your first library card. Can you talk about the power that books have held for you since that moment?

The hair on the back of my neck still raises when I start writing, or when I read or listen to a book. Everything I am is because of books.

Did you have a chance to reconnect with that librarian later in life?

I never did see that librarian again; I don’t even know her name. She never knew how she saved me,what I owe to her, and I have always wished I could thank her and show her my books—all those mind pictures she first helped me to find. I’m sure she would have been surprised that the grubby kid from the streets became a writer.

I honor the work that librarians and teachers do. They’re on the front lines of the battle to put books intothe hands of kids, and I hope they know what that means to kids like the one I was. So, to everyone reading this interview, thank you from the bottom of my heart. Any success I have is because of peoplelike you. We do this together, and I am grateful.

“I honor the work that librarians and teachers do. They’re on the front lines of the battle to put books into the hands of kids, and I hope they know what that means to kids like the one I was.”

You describe the fact that you didn’t fit into a traditional educational setting. Do you have encouragement or advice to offer those kids who struggle in school today?

My only encouragement is to hang in there, it does get better—I’m living proof of that. Nothing that’s happened to me was ever supposed to happen to anyone like me. Read. Read like a wolf eats. Read what they tell you not to read; read under the covers at night with a flashlight; read instead of watching TV or going online; just read. There’s a book for everyone; keep looking until you find it.

“Read. Read like a wolf eats. Read what they tell you not to read; read under the covers at night with a flashlight; read instead of watching TV or going online; just read.”

Which of your books made the biggest difference in your life?

Dogsong was the book that changed my life the most and the fastest; once it won the Newbery Honor, we weren’t dead broke any more, and we moved from the shack we were living in to a real house with a thermostat and indoor plumbing. We’d been living hand to mouth, raising our own vegetables in a garden, and I tracked and hunted for our meat. It was pretty barebones living, but Dogsong changed all that.

Gary Paulsen talks about how the natural world shaped him as a writer:

The woods, the sea, dogs—they not only shaped me as a writer, they saved me as a person. I alwayssay that I’d be nothing and nowhere without that librarian who gave me a library card and the first book I ever read, but there would have been nothing to save if I had not first found sanctuary in thewilderness. I ran to the woods when things were bad at home because I was safe there, nothing hurt, and I knew how to survive. I never felt like that at home or in school. I found safety and a place where I belonged, first in the woods and then in the pages of a book. I’m never far from either now.

The woods, the sea, dogs—they not only shaped me as a writer, they saved me as a person. I alwayssay that I’d be nothing and nowhere without that librarian who gave me a library card and the first book I ever read, but there would have been nothing to save if I had not first found sanctuary in thewilderness. I ran to the woods when things were bad at home because I was safe there, nothing hurt, and I knew how to survive. I never felt like that at home or in school. I found safety and a place where I belonged, first in the woods and then in the pages of a book. I’m never far from either now.

Which of your books are you the proudest of?

I’m probably always proudest of the most recent book I’ve finished. It’s such a thing…to start with nothing—a word, a memory, an idea—and sit down and let the story take you, like a dogsled team, just snake out in front of you, and all you can do is hold on to the bar and see where you go next.

Gone to the Woods illuminates some of the most important elements from your younger years, particularly the natural world and books. How are those things still part of your life today?

I read every day—paper-and-ink books at night, and audiobooks on my commute to and from mywriting shack. And I go there, to sit at my desk and work on new books I’m writing, every day. Every single day. The shack is in the mountains. There are no neighbors except for the rattler under my deck—I named him Carl— so when I need a break from writing, my dog Gib and I hike around my property. And I’m building a greenhouse so I can grow my own lettuce and tomatoes this year. I’ll probably only get one sandwich worth of food at the end of the season, but I’ll get it done.

Speaking of writing every day, I know that you have at least two middle grade novels in the works. What do fans have to look forward to?

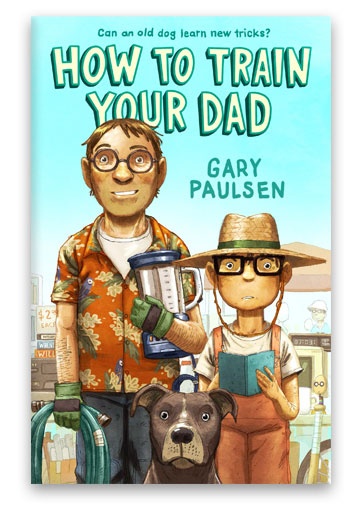

How to Train Your Dad will be released in the fall of 2021, and Northwind will be published in January 2022. The first is, I hope, a funny book about a father and son living off the grid (it made me laugh when I was writing it and again during the edit and copyedit process). Northwind is, again I hope, a grand historical action adventure. And I’m working on more book ideas that no one’s seen yet. I’ll keep writing if you keep reading; let’s keep this dance going.

“I’ll keep writing if you keep reading; let’s keep this dance going.”

Is there anything else you’d like to add?

We’re working on my website—GaryPaulsenAuthor.com—but social media is not my thing. The advice I have for educators, librarians, and readers is to READ LIKE A WOLF EATS.

And thank you. Thank you for reading my books and recommending them to young readers. Thankyou for doing the heavy lifting of the book industry—you’re the ones on the front line of battle putting books into the hands of young readers. Thank you. I’m still writing, I hope you keep reading.