Every kid loves learning about animals: the ones they want to cuddle, the ones they want to run away from, and the ones that can be gross sometimes. Having a variety of high-interest books in your library is a wonderful way to teach your students that learning can be enjoyable. In today’s guest post on the Mackin Community blog, author Jason Bittel shares how books about nature and animals can encourage an interest in science.

Hi. My name’s Jason Bittel, and I write about animals for a living. Because that’s a thing you can do.

For nearly a decade now, I’ve gotten to learn about every kind of critter you can imagine for publications such as National Geographic and The Washington Post. I’ve reported from the savannas and shrublands of South Africa and the dry tropical forest of Costa Rica. I’ve eaten termite warriors and sniffed sloth turds.

From the cute and cuddly to the scaly, scary, hairy, and extraordinary, I’ve yet to find a creature that doesn’t fill me with wonder. But here’s the thing—I don’t just think animals are cool and fun, I think they can be lifechanging. And here’s why.

When I was little, I wanted to be a marine biologist. Then a botanist. Then a veterinarian. But all of that came to a screeching halt in junior high, thanks to a particularly stuffy chemistry class. All of a sudden, the whole field of science seemed to be reduced to the memorization of equations and the names of old dead guys. My science spark fizzled and I threw myself at English and writing instead.

Of course, I never lost my interest in the natural world. I was still that kid flipping over rocks in search of life, plucking crayfish out of the creek, and poking dead things with a stick. So, as I grew up, earned a few degrees, and began pursuing a career as a professional writer, I pretty quickly realized that my destiny was not to write advertising copy for healthcare and higher education clients—it was to follow my wonder about the world all around me, the same wonder that bubbled up every time I spotted an anthill or an abandoned cicada exoskeleton.

Over my career on the animal beat, I’ve noticed that the stories that resonate most with readers (of all ages!) are the ones that teach them a surprising fact about an animal they think they already know. For instance, the fact that porcupines cannot shoot their quills, or that, in the wild, rabbits don’t actually eat carrots. These may seem like silly factoids, but they can also be launchpads for discussions of anatomy, diet, and evolution!

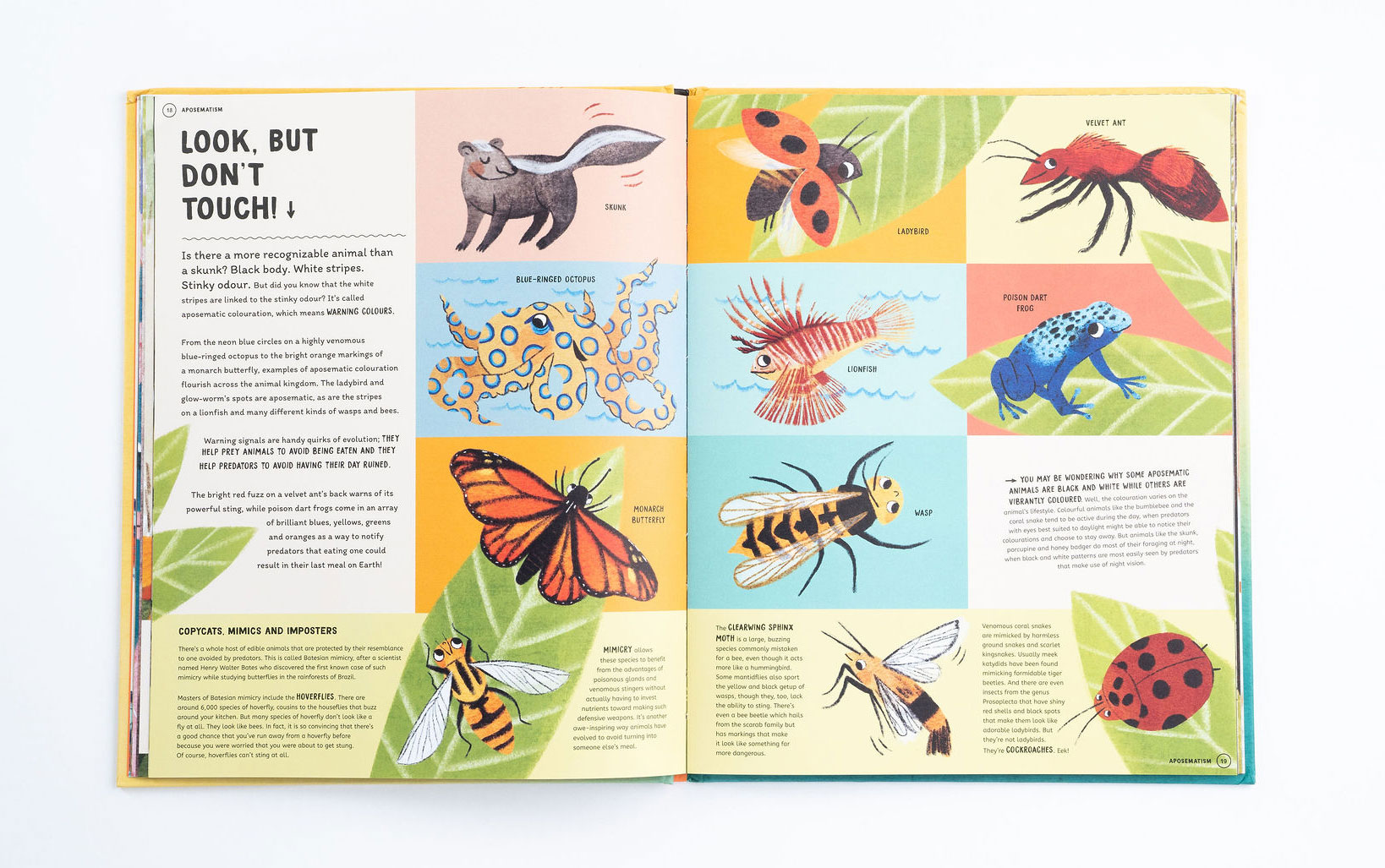

Take the skunk. Everyone knows its stink is a natural phenomenon to avoid. But what few realize is that skunk spray can also teach us about predator and prey relationships, why some animals develop striking color patterns, and about how foul-smelling derriere discharges are actually a kind of chemical warfare.

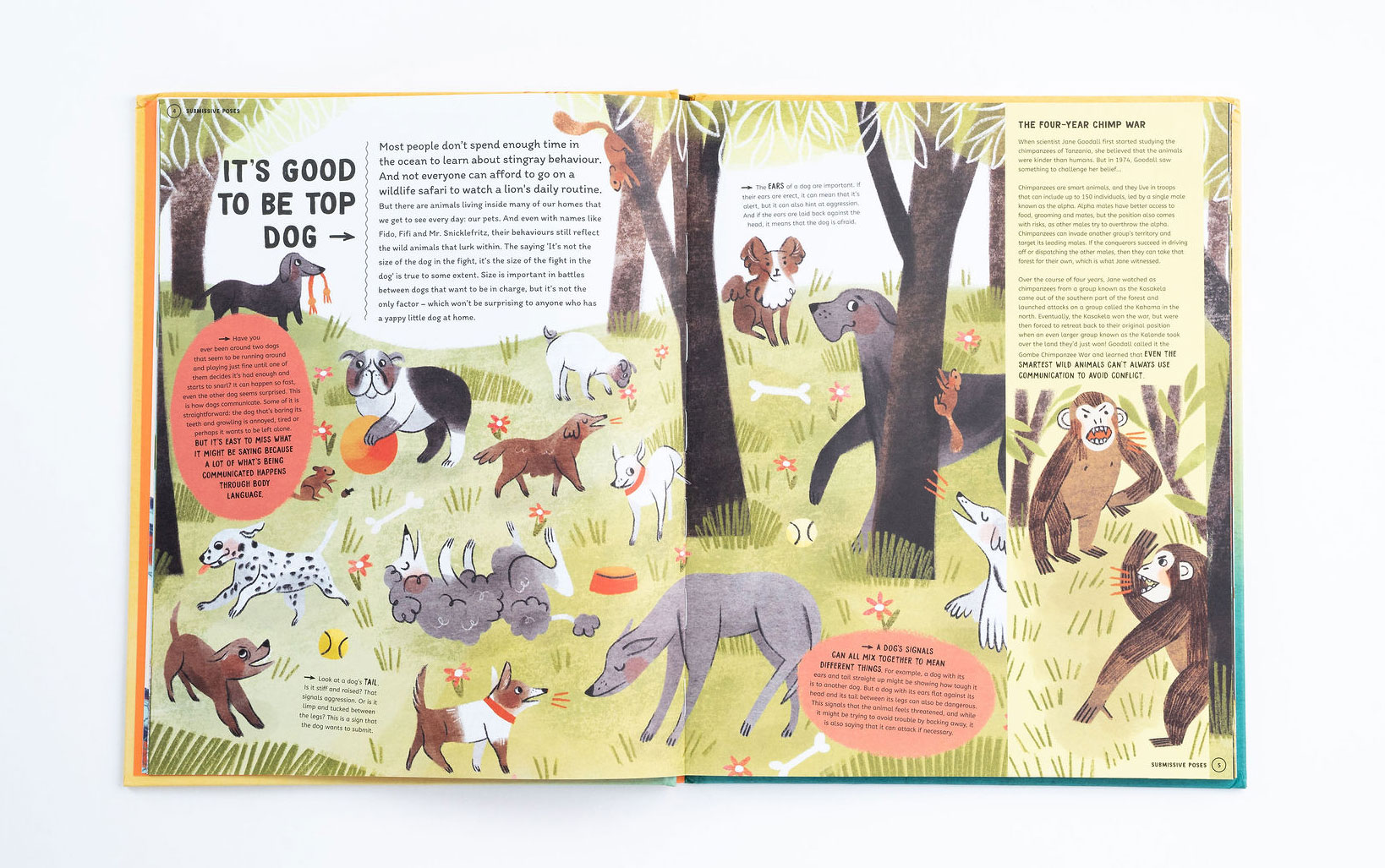

And it’s the same thing with a dog peeing on a lamppost. You might think the behavior is gross or obsessive—hurry it up, Sparky, we don’t have all day! —but this simple act is rooted not just in waste removal, but also complex intraspecific communication. Each tinkle is a secret message coded in pheromones and chockful of doggo stats, such as sex, reproductive status, and maybe even size. So, the next time your dog sniffs 10,000 objects between the beginning and the end of a walk, realize that she’s not just smelling the roses—she’s actually swiping through canine social media!

Finally, I’d like you to consider the firefly. We called them lightning bugs where I grew up, and we’d run around trying to catch the buggers on many a summer’s eve. Not only are fireflies magical-looking creatures with their light-up butts, but they are also extraordinary animal ambassadors due to their harmlessness. Kids and even adults that might shy away from a shiny, wriggling worm or a menacing-looking ant can usually be coaxed into holding a lightning bug. They fly low and slow, do not sting or bite, and will even flicker their lanterns on and off while crawling over your fingers or sleeve, allowing virtually anyone to enjoy their display without much effort.

What you may not realize is that some fireflies are cannibalistic killers.

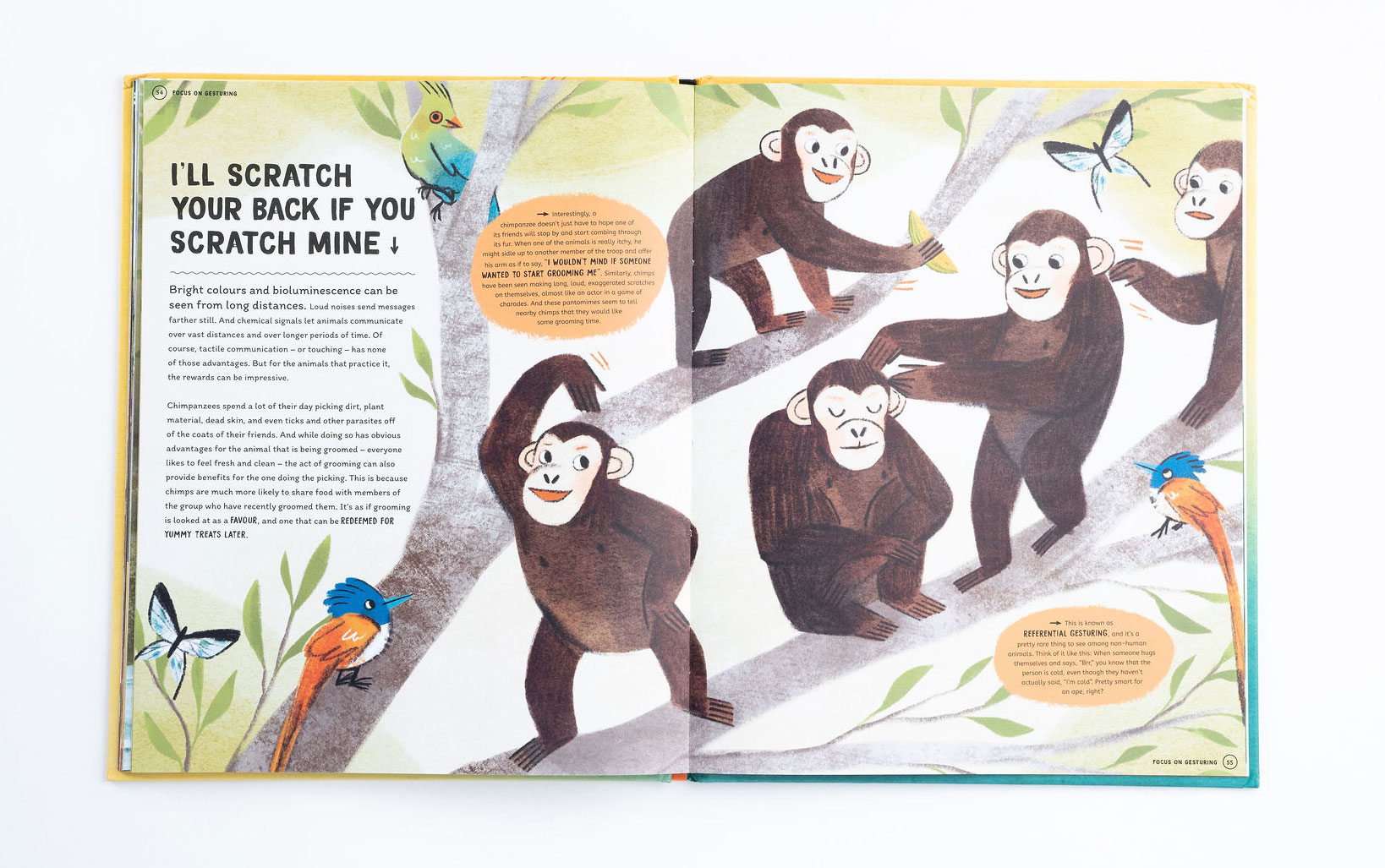

You’ve probably never thought much about it, but every time a firefly lights its lamp, it’s actually initiating a controlled chemical reaction sequence within its own body. And over millennia, each lightning bug species has developed its very own dialect of flashes, each of which varies in color, pattern, duration, and location. And females of the Photuris versicolor complex actually use that specificity against their kin. In fact, these so-called femme fatales have evolved the ability to mimic other fireflies’ flash patterns. When a hapless male zeroes in on her flashes and hovers down near the femme fatale’s perch, she pounces and devours him, bit by bit.

Why? Well, scientists believe that the femme fatales don’t have as many nasty-tasting, predator-repelling compounds in their own bodies that are present in other species of fireflies. So, they chow down on the ones that do, absorb their powers like some kind of supervillain, and then pass those defenses down to their own eggs.

Now, I want you to think about the rabbit hole of knowledge you just tumbled through. Even though we didn’t use these words, you just learned about the mechanics of bioluminescence, the dangers of visual signaling and mate choice, and even toxin sequestration! All because of a few fireflies.

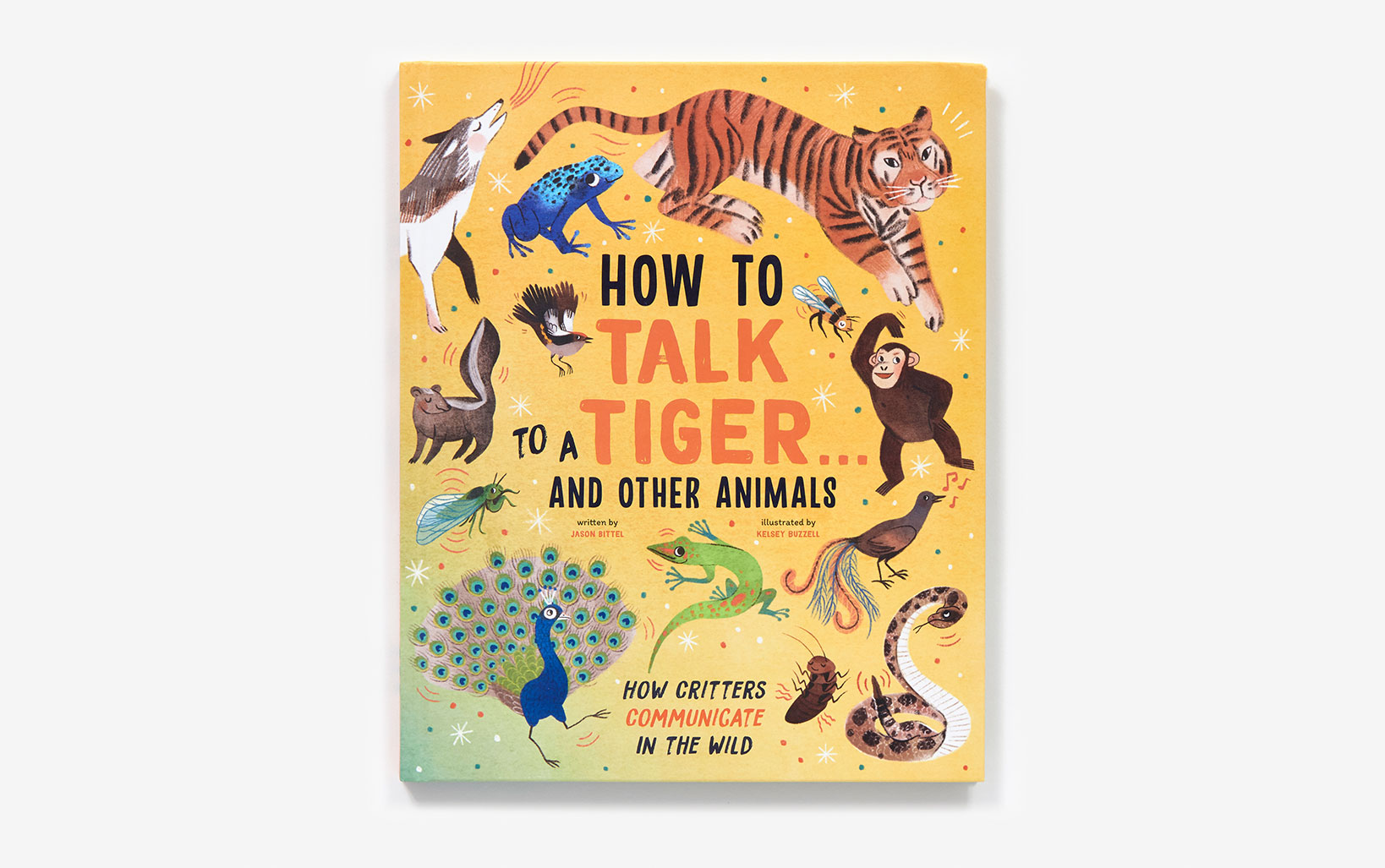

The best part is, every single animal on Earth has a lesson plan hiding inside of it! My new book, How To Talk To A Tiger…And Other Animals: How Critters Communicate in the Wild is full of great white shark secrets, bee waggles, deer sneezes, jackdaw staring contests, singing toadfish, head-banging mole rats, and poo-flinging hippopotamuses. I hope it can also set kids on a course toward science literacy—a path I came very close to missing out on myself.