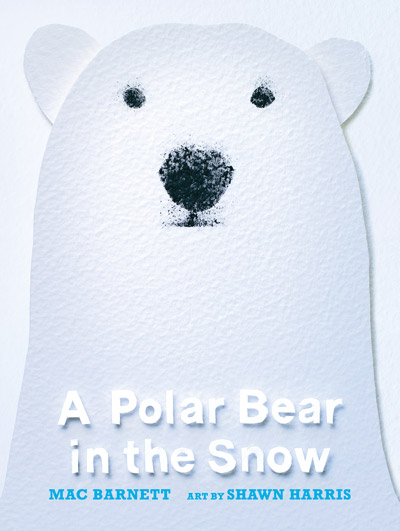

Shawn Harris is an award-winning artist and illustrator. In today’s guest post on the Mackin Community blog, Harris explores the intersection between picture books and comics, and how to use illustration to tell a better story.

I’m watching a video of author Mac Barnett reading an advance copy of our new picture book, A Polar Bear in the Snow. His voice is familiar, like a family member. We’ve known each other since we were seven years old, making him my oldest friend. “There is a polar bear in the snow. Still asleep, he lifts his nose and sniffs the air—and he awakens.”

This year, in the pandemic-induced tumult, Mac started a book club show on Instagram, for kids who were suddenly isolated at home and were searching for education, entertainment, and maybe most of all, structure. Now his voice is familiar to families around the world—on all seven continents, even Antarctica—who tune in to Mac’s Book Club Show every Saturday.

They’re the audience Mac is reading to now. “There is a polar bear in the snow. Where is he going?” he continues. I lean forward as he turns the page—this is my favorite part. The climax of the book happens with a single word: “Oh!” Mac reads, and pauses a beat. Then two. Then three. I know what he’s waiting for– the kids watching at home to finish answering his question. Because even though Mac has not written the answer, my illustration does reveal the bear’s destination. It’s the first moment of color in the book, a brilliant blue after pages of white. The polar bear has reached the sea.

What a unique trick that books with pictures are able to pull off: showing without telling. Novels can’t do that!

As a picture book illustrator, I thought our artform was alone at the vanguard of word-and-picture storytelling until recently, when my notion of what that combination is capable of exploded in all directions.

I started reading comics.

To clarify, I started reading them again. Like a lot of kids, my awkward stage between picture books and getting into “real” picture-less books was occupied by comics. But when I became a good enough reader to enjoy novels, I unwittingly dismissed comics as a tool meant to wean readers like myself off of books with pictures. So even though I loved pictures (I became an illustrator, after all), I stopped keeping up with comics. It wasn’t until an editor asked me if I had any interest in creating graphic novels that I thought seriously about comics again.

While reading comics, I immediately recognized a similarity with picture books that ran deeper than the possible presence of a cartoony character. They share the visual vocabulary that I’m so interested in as an illustrator, employing various combinations of showing and/or telling. But where a picture book maker might play the visuals against the text a few times in a book, comics employ these tricks with deft frequency — often multiple instances on a single page. For example, let me show you just the text from the first six pages of the graphic novel This One Summer by Mariko Tamaki and Jillian Tamaki:

Crunch

Crunch

Crunch

Crunch

Crunch

Okay. So. Awago Beach is this place.

Where my family goes every summer.

Ever since…

like…

forever.

“Rose.

Fingers.”

Your brow might be furrowed. “Six pages?” you might say. “What is even happening?” True, the manuscript is half (if that) of a story. Most of the sentences are even half-sentences. Can you imagine writing and submitting a half-finished piece like this to a publisher or agent? Well, maybe we should because when it’s coupled with the illustrations, the outcome is wholly engaging. Here’s what the pictures add:

We begin in a memory. An exhausted child in flip-flops is being carried by an adult along a sandy path to a cabin at the edge of a wood. We cut to present day and see a sedan equipped with a canoe rack sitting in a line of traffic. In the backseat is a girl (a few years older than the one from the memory), who sits biting a thumbnail and reading anime. When her mother glances in the rear-view mirror, she reprimands her daughter — whose name, we learn, is Rose — for her nail-biting.

I mean, this is some advanced, tightly packed, nuanced storytelling here, and the craziest thing is, it reads intuitively. This isn’t a Rachel Cusk essay, it’s YA (thematically) with middle-grade-age characters (accompanied by mostly their vocabulary). I think many authors would be tempted to bring more words to the project, but Mariko is expertly chill, delivering lines true to her characters — a restraint especially remarkable next to the abundant mood Jillian’s two-toned drawings bring to the page in addition to delivering a huge portion of the narrative. Seeing Jillian’s illustrations carry so much weight, it’s no wonder she’s as big a name in picture books as in the comics world. She’s a master of this language. You can see her work in Julie Fogliano’s picture book My Best Friend, where before the text begins, Tamaki wordlessly breaks the fourth wall, skillfully placing our empathy with a second character caught in the gaze of a potential new friend on a playground. By the time the author begins, “I have a new friend,” we’re already primed and invested.

And there are more book makers bringing their takes on visual-language stories from comics to picture books (and vice versa). Isabelle Arsenault blurs the line between the forms with her book Albert’s Quiet Quest, which alternates between pages laid out in panels like you’d find in her graphic novels, and full-spread illustrations like in her picture books. Other creators publishing work in both mediums include Lisa Brown, Jessixa Bagley, Greg Pizzoli, Eleanor Davis, Vera Brosgol, and Laura Park.

In the video I’m watching, Mac finally turns the page. The next sentence he reads confirms what kids watching at home already know: “He is going to the sea!” I imagine our audience and their variations on the exclamation “That’s what I said!” It strikes me that a comic might have stopped at “Oh!”, the hero atop a vista overlooking the gleaming destination. But hearing the confirmation is fun here, like hearing “ding ding ding” after a correct answer on a quiz show.

This show-then-tell trick creates an interaction with our audience that mimics a conversation. It works best when spoken, and unlike a comic, our book is most often read aloud.

Despite the difference, innovations happening in the other print medium are ripe to be translated into picture books, and it’s my hunch that more serious comic readers in our field would only serve to enrich our already exciting art form.