Daniel Nayeri’s latest middle-grade book, Everything Sad is Untrue (a true story), is an autobiographical work of fiction. In today’s guest post on the Mackin Community Blog, Nayeri presents a photo essay about the real-life people behind the characters in his novel. This essay is written as if he is the student in his novel, completing an assignment for his teacher, Mrs. Miller. The photos shown here served as part of the inspiration for his novel, so we are thrilled to get a peek into the real characters from the book.

In an Oklahoma middle school, Khosrou (whom everyone calls Daniel) stands in front of a skeptical audience of classmates, telling the tales of his family’s history stretching back years, decades, and centuries. At the core is Daniel’s story of how they became refugees—starting with his mother’s embrace of Christianity (forbidden in their country), and continuing through their midnight flight from the secret police, to the sad, cement refugee camps of Italy, and then finally to asylum in the U.S. Nayeri deftly weaves stories of the long and beautiful history of his family in Iran, adding the richness of ancient tales and Persian folklore.

Like Scheherazade of One Thousand and One Nights, Daniel stands in front of a hostile classroom and spins a tale to save his own life: to stake his claim to the truth. Everything Sad is Untrue (a true story) is a tale of heartbreak and resilience that urges readers to speak their truth and be heard.

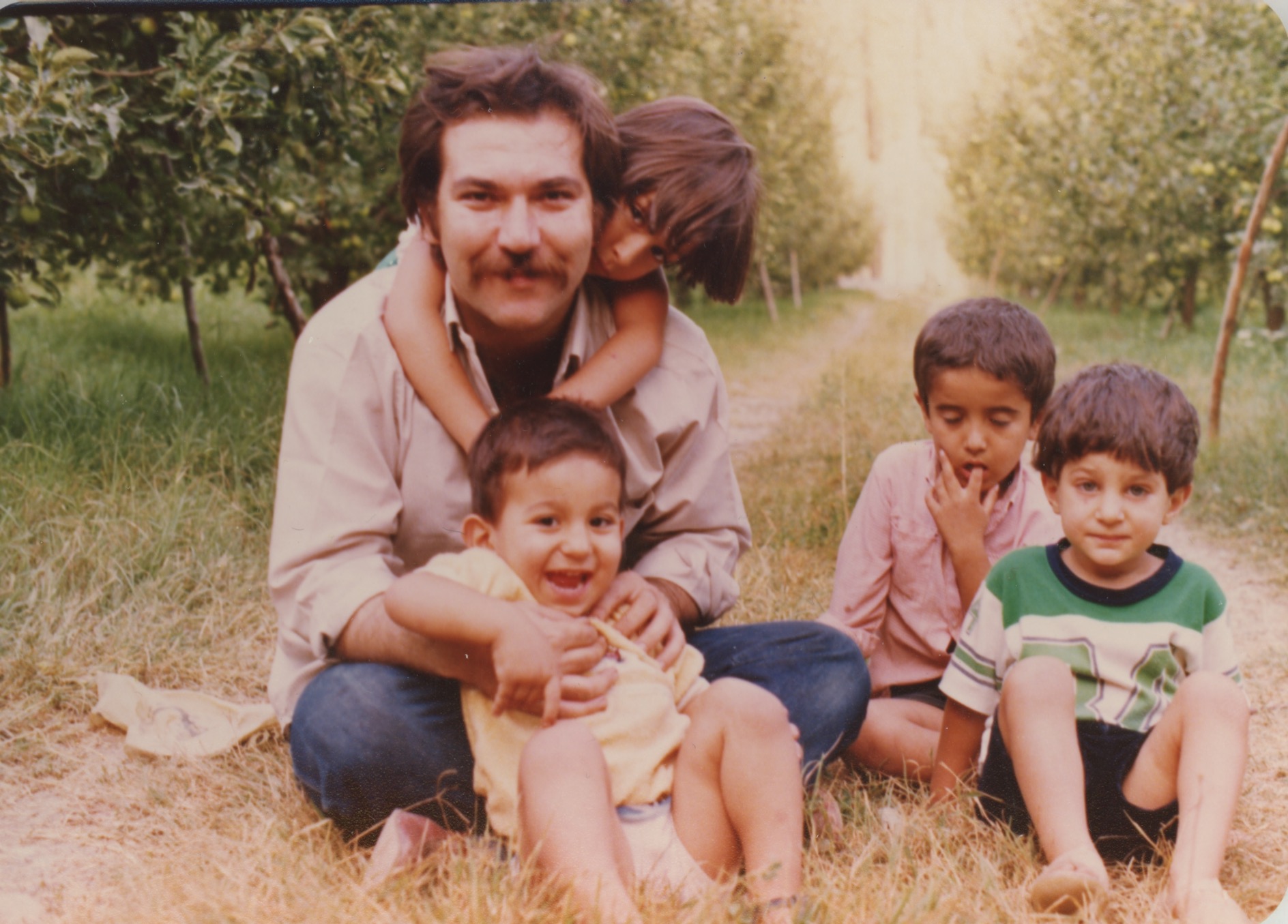

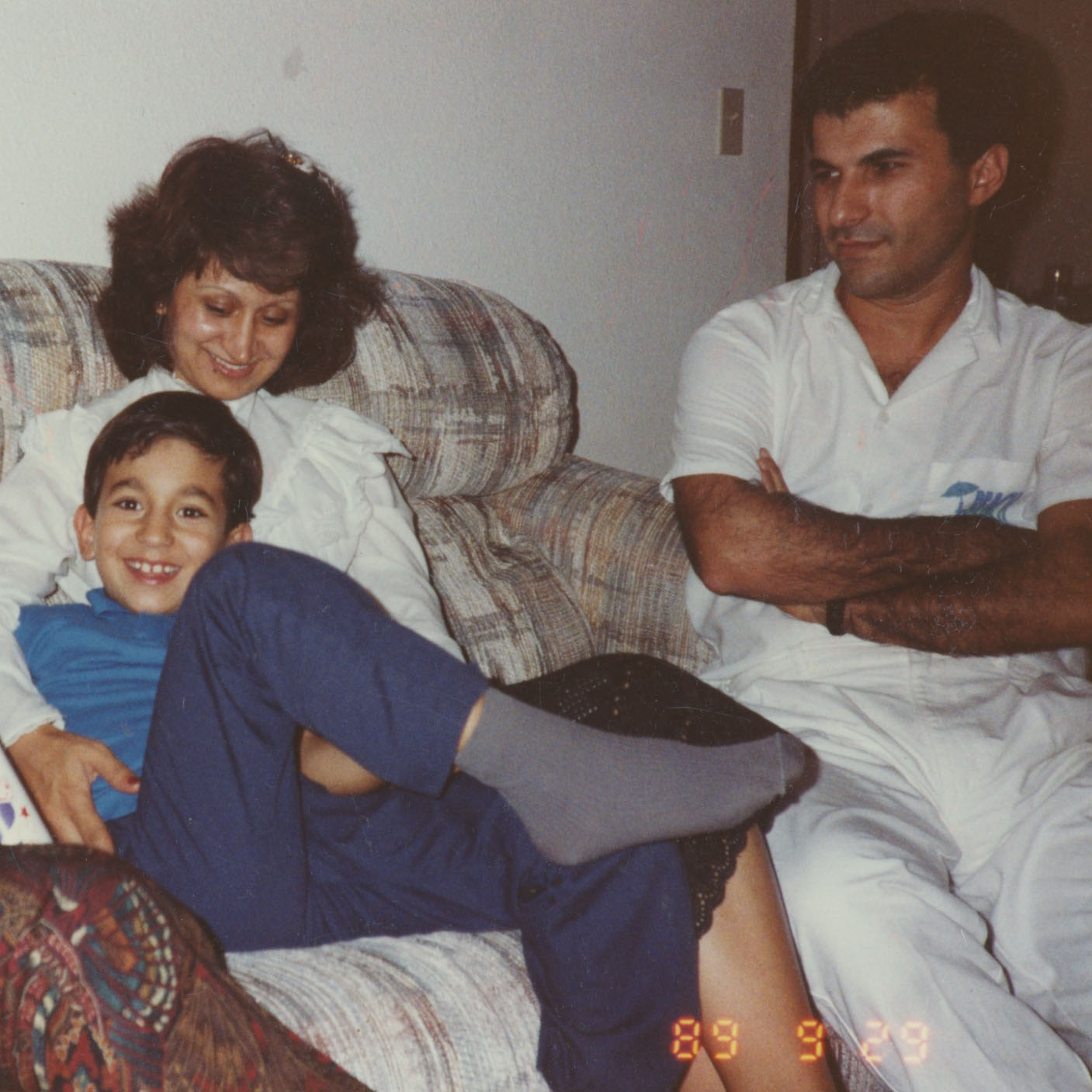

Alright Mrs. Miller, if you have to see a picture for this assignment, then here: here’s me right now wearing a sweater in Oklahoma even though it’s summer. Seems happy enough, right? That’s a happy smile that people make, yes? People like happy people better. So, you should tell me if I’m unlikeable in this picture. I can find something else. How about this? Better? This is cheaty cause it’s me when I was a little kid. Little kids are happy cause they don’t know any better. That’s why people like little kids. Look at him. He’s basically brand new. Imagine the world when you’re brand new. He could be smelling honeysuckles for the first time in that picture, which we had in our house in Isfahan, which is where this was taken. Or a butterfly just flew past his face in my Baba Haji’s orchard in Ardestan. Who knows? The point is little kids are happy for little things.

And besides, back then I could sit in my dad’s arms like this.

Daniel in his dad’s arms.

My sister is in the back of the picture, haunting it. My mom is here in this picture, so you can see we were rich in happiness. It was only a year after this that we exploded. My mom converted to Christianity after we visited my grandmother—who was exiled in England—and my sister saw a miracle. When we got back to Iran, my mom went to the underground church, until the secret police took her, (you probably don’t want to know about them) but we escaped and became refugees in Dubai. I should tell you now that my dad didn’t come with us. I don’t have good reasons or answers for any of this.

Family picture in Italy.

Here is a picture of us in Italy, hoping America will give us asylum, before we knew how to look into cameras so they can’t tell what we’re thinking.

And now you might be thinking—if you’ve gotten this far, to the part where we got to Oklahoma and we’re poor, and no one would believe that we were ever anything else–you might be thinking, “Who’s that guy?” That’s Ray. He can beat up anybody. That’s all you have to know about him.

Ray with family in Oklahoma.

Anyway, those are the “main characters of my life story,” which is an odd writing assignment if I’m being honest. But there is also Mrs. Miller’s whole class, who listens to me read my assignments about the feast in my Baba Haji’s house, my ancestor who saved the daughter of a Parsi king, and our house in Isfahan with the birds in the walls, and—like King Shahryar who listened to Scheherazade tell the 1001 stories–they are highly skeptical. But these are my memories, and they’re all I’ve got. So, I wrote them down to keep them from disappearing. And as I write them, I realize, like you—Reader and Mrs. Miller—that a patchwork memory is the shame of a refugee. These are all the pictures I will ever have. And now you’ve seen them. You’ve got as many of my memories as I do. Maybe you know things now that I’ll never know. But I will write them all so that I never forget my Baba Haji. Someday, I will wake up every morning before my family wakes up—I’ll be grown up by then in New Jersey or someplace, with a wife and a son I’ll never give over to anybody—and I’ll write it all down in a book. And not just the sad parts, but the happy little kid parts too. And now, Mrs. Miller, I believe I have performed this assignment at the A-plus grade level. Thank you.