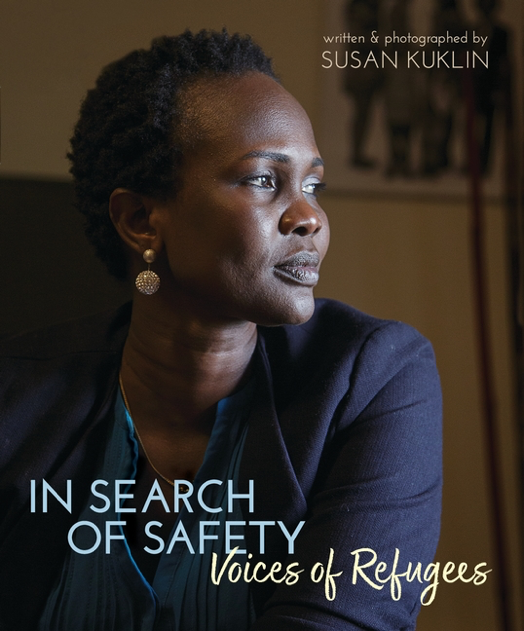

Susan Kuklin is a photographer and author of nonfiction books for children and young adults. In today’s post on the Mackin Community blog, she leads us through the process of finding her voice as an author, and shares how that journey prepared her to amplify the voices of refugees in her newest book, In Search of Safety.

Like all of us who are social distancing, I’ve had a lot of time on my hands; time to read, time to do something constructive. While most of the items on my constructive “to do” list remain unchecked (how about yours?), I have used this period to think and blog about my process when writing nonfiction books that are based on real people’s interviews.

My approach to nonfiction books started with my first book, Mine for a Year, a story about a twelve-year-old foster child named George who was raising a guide dog. What made George’s story so unusual was that he himself was going blind. At first, the project was a photo essay to sell to a magazine. But as I got deeper into the subject, I thought this could be an inspiring book for tweens. Easy breezy.

Ha!

I wrote the book in unpretentious and simple language because the storyline was down-to-earth and direct. After editing the photographs, I decided to show it to a gifted magazine editor who I had worked with many times. I gave him the carefully typed text and sat across from his desk, waiting, assured and confident, for those magical words about becoming the next Judy Blume.

The editor read the first paragraph or so and slammed the manuscript on this desk. “I’m not going to read this crap!” he said, using stronger language. “Anyone could write this. Where’s the voice? Really, Susan? REALLY???”

Looking back, I’m glad he was honest. At the time, though, I crawled under the sheets for a few days, vacillating between furious and embarrassed. While under said sheets, I thought back to college and graduate school when I was a theater major at NYU. One of the more important classes taught the process of interpreting a character—how to get inside the playwright’s words in order to create a living, breathing personality. There were unorthodox assignments: 1. Go to the zoo and chose an animal that best represents the character. Learn and study its movement. 2. Go to a museum and find a painting that reflects the mood of the character. These exercises had everything to do with observation and concentration. It was very Zen.

I loved it!

Why not give the old technique a try? I went back to visiting George and his adorable puppy and watched. How do they play together? How does George talk, walk, sit, slump, flip his hair with the back of his hand, tip his head in an ironic display of confused amusement? I listened to his voice, observing syntax and repetitious phrases he often used. Then I concentrated on details: What exactly did he eat for breakfast? What colors were the flowers outside his home? How did he wear his baseball cap? The key to understanding a character is in the details. When I felt really, really ready, I went back to the typewriter (remember those?) and wrote Mine for a Year in George’s voice. First-person literature. By turning he into I, I found my voice.

Jump forward.

My new book, In Search of Safety: Voices of Refugees, is written from the point of view of the participants: Fraidoon from Afghanistan, Nathan from Myanmar/Thailand, Nyarout from South Sudan, Shireen from Northern Iraq, and Dieudonné from Burundi. Each person has a distinctive manner of expression that reflects their particular culture. Each voice has its own music, sharps and flats, whether speaking in English or the language of their birth country.

My new book, In Search of Safety: Voices of Refugees, is written from the point of view of the participants: Fraidoon from Afghanistan, Nathan from Myanmar/Thailand, Nyarout from South Sudan, Shireen from Northern Iraq, and Dieudonné from Burundi. Each person has a distinctive manner of expression that reflects their particular culture. Each voice has its own music, sharps and flats, whether speaking in English or the language of their birth country.

Fraidoon punctuates emotional sentiments with words like “forever” and “ever.”

When Nathan says the word “American,” his face lights up.

Nyarout often exchanges the phrase “I am” to “I be.” When she uses “be,” my face lights up. Considering her life experiences, it’s the perfect word for her.

Shireen, a recent arrival, having been captured and sold into slavery by ISIS militants, spoke only Kurmangi. We spoke through a translator. But one didn’t need a translator to understand the anguish this brave and extraordinary woman went through. I cried throughout the long interview and then again during every draft.

Dieudonné. Dieudonné is an activist; an organizer; a take-charge kind of guy. His enthusiasm is balanced with charming self-effacement, e.g., “I used to be smart.”

Four of the five refugees spent their formative years in refugee camps where they had few options and little hope for a productive future. Fraidoon spent years as an interpreter for the U.S. military during the war against the Taliban, putting himself in great danger on more than 500 combat missions. All five refugees were resettled in the state of Nebraska where they were warmly received. That inspirational feature had to be included too.

The experiences the five refugees shared with me are personal and intimate. To bring them to the page though, the chapters need to have a shape, a theme, a distinctiveness, and a purpose. That’s my job. I take some of the recorded words, and write their story, adding observations and details. Each profile is written in the name and voice of the participant. Before sending a final draft to my editor, each person reads what I wrote, checking for accuracy and tone. This continues throughout the editing process.

The people featured in In Search of Safety will inspire you. I promise. Their experiences—both traumatic and successful—will give readers hope and perhaps inspiration. In particular, their stories will motivate us to hang tough as we worry about loved ones and first responders through these dark, difficult days. We can do this. We will find safety. And joy. Together.