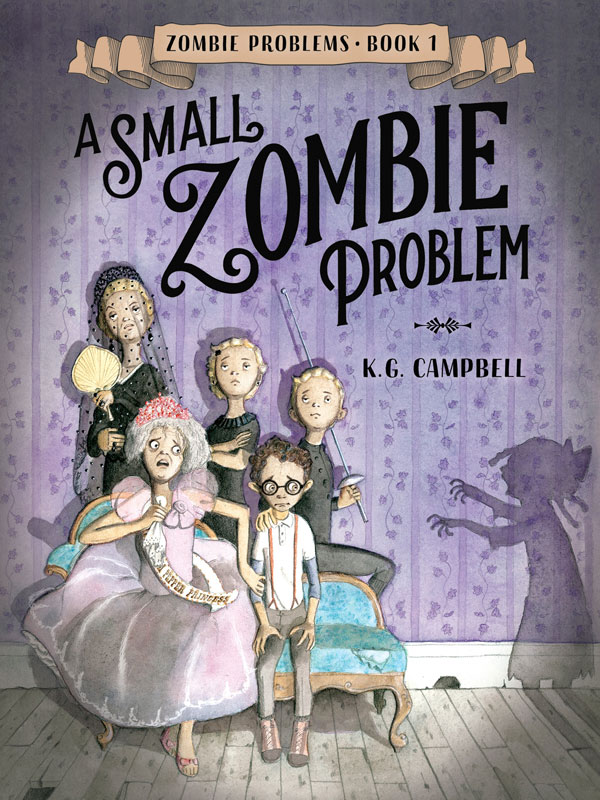

Today we are welcoming author and illustrator K. G. Campbell to the Mackin Community blog. In this post, he invites readers into his childhood in Scotland where he grew up loving Gothic stories. He further describes how the Southern Gothic genre, and a childhood memory from his spouse, inspired the creation of his newest book, A Small Zombie Problem, which we hope you will take time to read.

Why Gothic?

It’s a little-known fact that Hogwarts is a real school. Okay, it’s not a school of wizardry. And, okay, it’s not called Hogwarts.

But the school is old, and it is turreted, and it is haunted. It is steps from the Edinburgh cafes in which Ms. Rowling famously created Mr. Potter, and it is widely acknowledged to have inspired the far more famous educational institution. Hey, even their names are not dissimilar. Hogwarts. Heriot’s.

I spent most of my childhood there.

From ages five to eighteen, my playground was flanked by an ancient kirkyard to the east, an ancient city wall to the west, and the looming ramparts of an ancient castle to the north.

Every Herioter (such is the term applied to its pupils) must learn to navigate the school’s immediate environs, Edinburgh’s Old Town. It’s a place of ankle-turning cobblestones, claustrophobic alleyways, gloomy spires . . . and history. Dark history. Murders most royal. Plagues. Grave robbers. Witch trials. One notorious and satanic warlock.

Is it any wonder then that this graduate of the “real” Hogwarts should develop a taste for the sinister, brooding, and unnerving? Is it any wonder, growing up in one of the most Gothic spots in Europe, that he should aspire to write a Gothic novel?

Why Southern Gothic?

All right, K. G., you say, Gothic we get. But why would a native of chilly, flinty, northern climes (even one who now lives in California) choose, in his very first novel, to dive right into steamy, fecund Southern Gothic?

Well, the evolution of books can be convoluted, shaped by various considerations, necessities, and even random vagaries. The Southern element of A Small Zombie Problem was the product of such a complex journey.

Like all stories, it started with a seed of inspiration.

I was an only child. A lonely only child. And, as a lonely only child, I was always intrigued by sibling dynamics. My sister-in-law will reminisce about a time when her younger brother (my husband) was a menace, at least to her.

She was twelve or so. He was eight or nine. She was popular. He was not. A child of divorce, he was moved around frequently, always the new kid. No doubt insecure and a little lost, he began to shadow his older, more confident and socially established sister.

She didn’t care for this. She had places to be, friends to impress. The last thing she needed was a hapless younger sibling lurching in her wake. She resorted to climbing out of windows to shake her unwelcome sidekick. And, on one now legendary occasion, she discovered the boy awaiting her in the flower beds below. Angrily she declared, “You’re such a zombie!”

And there was the seed. What, I wondered, if the obstacle to a child’s quest to make friends was an actual zombie? And what if that quest was rendered more compelling by the fact that the child had never had a friend. What if the child was desperately lonely? Now that was a child I knew, a character I could write from experience.

I wrote a pitch titled A Small Zombie Problem. Someone liked it. I was encouraged to develop it.

My literary career had just taken off, so it took me a few years, but when I returned to my zombie idea and began to lengthen and deepen its plot, it became immediately apparent that my zombie required an origin. There had to be a “why” for its existence.

Contemporary zombie-based entertainment generally presents us with an undead that is the product of an apocalyptic virus. Brain eaters. An expression, surely, of a cynical, nihilistic zeitgeist. But any zombie historian worth their salt knows that the origin of the word and the concept lies in Voodoo, the syncretic religion that combines African spiritual beliefs with Catholicism.

So suddenly, I was writing a book about Voodoo. And if you’re writing a book about Voodoo (at least in the Anglophone world), you’re writing a book about Louisiana.

In the end, the Voodoo was nixed. Religion—obviously a sensitive subject—does not sit well with lighthearted middle-grade fantasy. And indeed, much of the local lingo that would have located the action (cher, bayou, levee) was also set aside. The intended demographic lacks the cultural exposure required to navigate such regional specifics.

But I’d become bewitched by the place. I even went there. To this northerner, Louisiana was so exotic and foreign. It delivered a whole new flavor of Gothic that I found . . . well, delicious! And like any good Gothic author, I determined to insert the setting into my story to a degree that it might be regarded as a primary character.

To most, Black River, Hurricane County, and Lost Souls’ Swamp will conjure up generic images of the American Southeast. But to those familiar with Bayou Teche . . . well, wink, wink!

Why Middle-Grade?

Three reasons:

One: I love middle-grade.

This lonely only, like so many other young introverts, discovered a lifeline in reading. Jane and Michael Banks, the Pevensie kids, Charlie Bucket and Grandpa Joe were all there for me when I needed them.

The books I devoured between the ages of eight and fourteen left a disproportionate impression upon my spongy, impressionable mind, and I’ve harbored great affection for middle-grade and younger YA ever since.

Two: My skill set.

There’s the practical consideration of what I bring to the table. I can write. And I can draw. I like writing. I like drawing. I like illustrating my own words. There’s an intoxicating sense of autonomy to the process of creating an entire world in word and image.

In the categories beyond middle-grade, my artistic talent becomes less relevant. Unless, of course, I write a graphic novel. But merely contemplating such an enormous undertaking increases my heart rate, leaving me rather sweaty and cold. Maybe one day. Probably one day. One day.

Three: Gothic suits the demographic.

Where horror leaps out at you wearing a hockey mask and wielding a bloody chain saw, Gothic lurks in the shadows, whispering spine-tingling insinuations in your ear.

Middle-graders have discovered death. They’re morbid little creatures with a penchant for gruesome demises, mild gore, and sinister goings-on, especially when served on a bed of darkly humorous fantasy. Think Roald Dahl, Lemony Snicket, Kelly Barnhill, Chris Priestley.

So why Southern Gothic for middle-grade? Surely a better question would be why not?