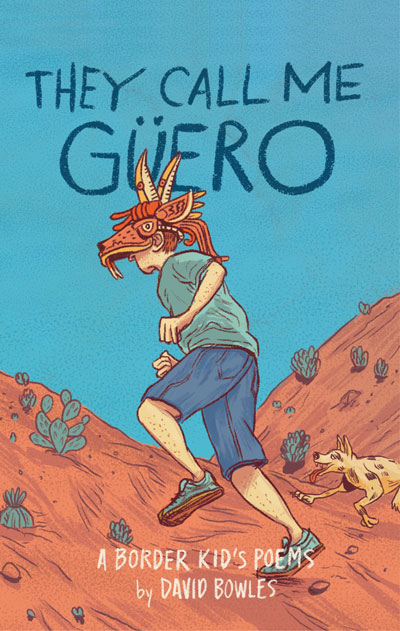

We are delighted to welcome David Bowles to the Mackin Community blog today. David is the author of the Garza Twins series and his most recent title, They Call Me Güero, which is a Pura Belpré Honor Book, along with numerous other honors and awards. In this post he describes his writing journey toward, They Call Me Güero, which has an inspiring outcome. We hope that you will take a few moments to read this post and then take an opportunity to read (or re-read) one of his books.

I’ve been writing off and on since I was in junior high school. But when I started writing in earnest, in my late 20s, I was already an English teacher, so I had to steal moments here and there to dedicate to my work-in-progress. After a while, I realized that my best bet was to get up at 5 am, drink a big cup of coffee, and plug away at the computer for an hour and a half before getting ready for a long day of teaching. Then, for half an hour each night, right before bed, I would look back over what I had written, making quick edits and leaving my next-morning self some notes.

I’ve been writing off and on since I was in junior high school. But when I started writing in earnest, in my late 20s, I was already an English teacher, so I had to steal moments here and there to dedicate to my work-in-progress. After a while, I realized that my best bet was to get up at 5 am, drink a big cup of coffee, and plug away at the computer for an hour and a half before getting ready for a long day of teaching. Then, for half an hour each night, right before bed, I would look back over what I had written, making quick edits and leaving my next-morning self some notes.

I did that for twenty years.

Granted, my family gave me a few more hours on Saturdays and Sundays, but mostly I had to figure out how to be as efficient as possible with my morning writing.

I became a planner. I map out everything I can ahead of time: characters, setting, backstory … and definitely plot. First this plan is just a rough, bulleted outline, but it expands so that there’s a paragraph for each chapter, detailing the major points.

Now, I have many writer friends who despise this practice. “Where’s the excitement if you already know what’s going to happen? Where’s the discovery and surprise?”

It’s there, still, I reassure them. In the planning process itself, and in the unexpected twists and turns the story decides to take even after you’ve mapped it out, like a wide-eyed father who decides to take the family on a “cool” detour to see the world’s largest ball of yarn.

Plus, publishers really want you to give them a synopsis of the book you’re proposing to write, and that’s hard if you’re just making it up as you go along!

The ironic thing … my dirty little secret, if you will … is that my most successful book ever wasn’t planned.

The ironic thing … my dirty little secret, if you will … is that my most successful book ever wasn’t planned.

At all.

The book is, of course, They Call Me Güero.

The book’s genesis was the poem “Border Kid,” commissioned by Sylvia Vardell and Janet Wong for their anthology Here We Go! (put together in response to the anxiousness kids of color were feeling at Trump’s election). The speaker of the piece is a Chicano kid living on the border who goes with his dad to the little town on the Mexican side. When they’re driving back, the border fence makes the boy sad, but his dad reassures him that it cannot stop his heritage “from flowing forever, like the Río Grande itself.”

That poem got reprinted in the Journal of Children’s Literature, and when I was inducted into the Texas Institute of Letters in April of 2017, it was one of the pieces I read at the ceremony. Afterward, Bobby Byrd of Cinco Puntos Press approached me, gave me a hug, and muttered in his inimitable drawl, “If you can write another 50 poems in this kid’s voice, I’ll publish that book.”

So I did.

“Border Kid” had been inspired by my earlier poem “Border Folk,” which contrasted my experiences as a half-Chicano child in deep South Texas in the 1970s and 80s with those of my son, a Gen-Z Latino. So it made sense to dig deeper in that fertile narrative ground. I also pondered the struggles of other kids we know, like the undocumented girls and boys in our community who now fear for themselves and their families. I’ve spent my entire life, nearly 50 years, in this community. I tried to become a conduit for its collective soul, letting line after line pour out of me.

It was liberating.

After a few poems, all these elements blended together in just the right balance, like a good pico de gallo. I could hear the boy just as clear as a bell. He didn’t need a name. He’s the güero, the light-skinned kid in his family, a 12-year-old with one foot in mainstream America and the other in his family’s Mexican American traditions. A gamer who goes to Spanish-language mass, a dreaming reader who runs through the chaparral with his dog. Mischievous and big-hearted, maybe softer than the men in his family might want, but ready to stand up for what he believes in.

I took stock of the poems at last, arranging them into sections. One briefly covered the highlights of the unnamed speaker’s 7th-grade year. Others covered celebrations, traditions, music, poetic forms, etc.

Bobby Byrd saw through all that false categorization. “It wants to be a novel-in-poems,” he told me via Skype.

I pouted for a bit, then re-read the manuscript. He was right. A story wanted telling.

Accepting Bobby’s wisdom, I rearranged the poems, putting everything in chronological order. Then we took stock, pulling out what didn’t fit the sort of loose plot and making note of the gaps in the narrative. At the end of the day, we realized that—in wanting to appeal to boys ages 9 to 13, a group notorious for not liking poetry—we needed narrative poetry, action, overarching plot, etc.

With that in mind, I set myself to creating additional poetical vignettes to fill in the gaps and address those needs. Before long, the book took on the basic shape it has now.

And readers love it, especially Mexican American kids. What a gift from the universe. My first organic project, resonating with so many people.

My mental Güero composed the poems he needed and wanted to compose, and in doing so, he traced his journey through this very difficult year. I hope that people of color and their allies, that everyone living through this precarious moment in US history, may feel themselves reflected in his own struggle and celebration.

Perhaps some desperate kid will hear Güero’s voice, just like I did, full of wild joy.

“Open your heart,” he whispers, “to the unplanned wonder of the world.”