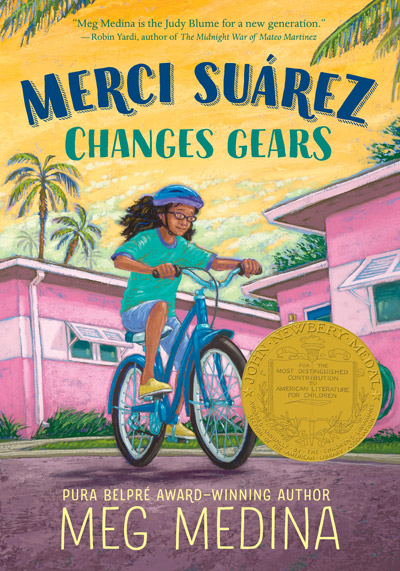

Her ears were buzzing. Her knees were buckling. Her mouth was babbling. Author Meg Medina remembers that much about the morning she received “the” call from the Newbery Committee telling her that her book Merci Suárez Changes Gears (Candlewick, 2018) had been awarded the coveted Newbery Medal. In her YouTube response, Medina shares her elation and appreciation to readers and committee members alike.

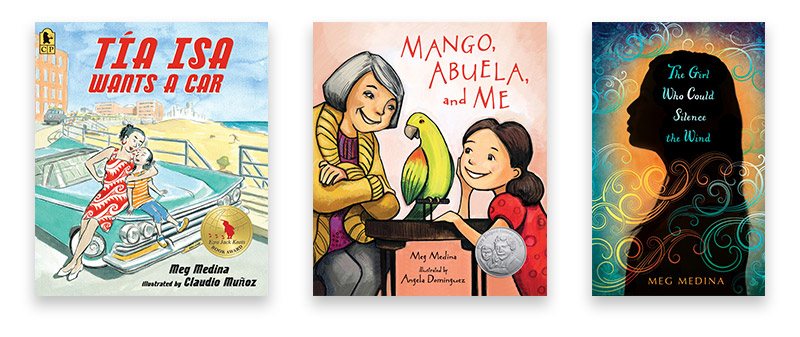

Just a handful of years ago, Medina emerged on the publishing scene with her picture book, Tia Isa Wants a Car (Candlewick, 2011). Since then, she has written six more titles which have received numerous accolades and awards including Pura Belpré Honors for Mango, Abuela, and Me (Candlewick, 2017).

“I could not have dreamed this scenario,” shares Medina. “The real question is what do you do with that precious gift? It has to amount to more than having a sticker on your book and a pretty medal sitting in a curio cabinet. For me, it has meant figuring out how to use my visibility to bring new authors to the table, and how to encourage readers—whether they’re parents, teachers, librarians, or young people—to read widely, diversely, and voraciously. It has meant using my visibility to be an ambassador of cultures to readers at a time when our country is wrestling with so many divisive narratives.”

Medina, known not only for her own books but also for helping new writers of color, has long advocated the need for increased diversity in children’s publishing. A founding member of We Need Diverse Books (WNDB) and now an advisory board member, Medina is proud of the work WNDB has done. She points to the use of social media to galvanize people in supporting a push to diversify publishing, and she identifies her favorite initiative as the intern program that places black, indigenous, and people of color in major publishing houses. “WNDB has done some very important work in the last five years, building on earlier efforts by other groups that were similarly alarmed by the

Medina, known not only for her own books but also for helping new writers of color, has long advocated the need for increased diversity in children’s publishing. A founding member of We Need Diverse Books (WNDB) and now an advisory board member, Medina is proud of the work WNDB has done. She points to the use of social media to galvanize people in supporting a push to diversify publishing, and she identifies her favorite initiative as the intern program that places black, indigenous, and people of color in major publishing houses. “WNDB has done some very important work in the last five years, building on earlier efforts by other groups that were similarly alarmed by the

pervasive whiteness of the world of children’s books. We need all voices in all parts of publishing—librarians, marketing people, editors, authors—to ensure that the work we make is authentic and excellent. It’s our duty to children.”

Medina identifies strongly with the responsibility to and needs of children, especially those who are young Hispanic females. To write for them, she mines her own life events and emotions for cues and clues to include in her books. “In the most essential way, I write for exactly one person: Meg as a child. I really try to channel myself at a particular age and think about the questions and fears I had at that age. I delve into my memories of specific events that have stayed snagged in my mind. I find that doing so frees me up to write the truth about growing up as I see it. And my truth, of course, invariable involves the intersection of culture, family and girls.”

Meg Medina: Author, Ambassador, Advocate

“I always loved writing, even back in elementary school, but it wasn’t an aspiration. I don’t think I even imagined that such a thing would be possible. No one in my family was a writer. No books I read were written by Latinas. I had no way of understanding how to break in [to the business] or how to make a living through words. The elders in my life were immigrants, basically working factory jobs to get by.

“But I believe that we are sometimes born for a certain path. I had lots of jobs before turning to writing for children. I was a public school English and writing teacher at multiple levels. I was a freelance journalist. I was a development director. I was a mother raising kids. When I look back, I think all of those career experiences prepared me for writing for kids. None of the skills I learned were wasted. I draw on all of it as a writer today.

“Almost every book I’ve written bears the emotional truth of my experience growing up a U.S.-based Latina. My Aunt Isa did buy our family’s first car as was depicted in Tia Isa Wants a Car. I did struggle with bullying the way Piddy did in Yaqui Delgado Wants to Kick Your Ass. I was witness to the year of Son of Sam in New York City that forms the backdrop of Burn Baby Burn (Candlewick, 2016). And of course, as in Merci Suárez Changes Gears, I belong to a Cuban family that had to face illnesses and death together.

“Almost every book I’ve written bears the emotional truth of my experience growing up a U.S.-based Latina. My Aunt Isa did buy our family’s first car as was depicted in Tia Isa Wants a Car. I did struggle with bullying the way Piddy did in Yaqui Delgado Wants to Kick Your Ass. I was witness to the year of Son of Sam in New York City that forms the backdrop of Burn Baby Burn (Candlewick, 2016). And of course, as in Merci Suárez Changes Gears, I belong to a Cuban family that had to face illnesses and death together.

“Really, the whole arc of my career as a writer has been a journey from frailty into a clearer sense of myself. In the early days of my writing life, I was just so thankful for any interest in my work that I didn’t think much beyond the thrill of seeing one of my stories published.

“Really, the whole arc of my career as a writer has been a journey from frailty into a clearer sense of myself. In the early days of my writing life, I was just so thankful for any interest in my work that I didn’t think much beyond the thrill of seeing one of my stories published.

“Over time, I’ve come to see that a writer’s life is bigger than a name on a book. I’ve been braver about being part of the important conversation in publishing around issues of representation. I’ve become willing to ask for things and advocate for ways of working that I think benefit not only my career, but also the careers of newer authors.”

In Medina’s books, readers will quickly see seemingly lost Latinas come into their own personhoods and strengths. They move from fearful to fierce with a side of humor mixed in for good measure. Her stories do focus on Hispanic culture, but they are also full of universal feelings and concerns that cross-cultural boundaries. Medina acknowledges that. “I think many Latinx kids will see their lives reflected in the people and events I write about. But I think children, in general, will see their experiences there, too. The connection with readers of all kinds happens when they read something that feels true about themselves and the world.”

Readers of Medina’s novels know she does not hold back when it comes to addressing challenging topics like abuse, bullying, poverty, drug use, and even Alzheimer’s in Merci Suárez Changes Gears. There is no sugarcoating trauma and darkness; she lays it out honestly for the reader. “I don’t think we help kids by lying to them about what it takes to grow up,” Medina says. “We don’t have to brutalize them, of course, but we should prepare them. We should give them a space in the pages of a book where they can see situations that require empathy and understanding. That’s how we can use books to create healthy people and interconnected families.”

“I don’t think the time is near for an end to diversity awareness in publishing. It would be so nice to tick a box and say, ‘we’re done.’ We are definitely improving, but that’s not the same as saying the work is complete. I think, in fact, that we’re only truly beginning to have the frank conversations that have been long overdue about how we represent people in books for children. We continue to need to unpack the overt and subtle ways in which we have all been complicit in keeping people’s stories in the margins. We continue to need to come together in the spirit of putting children’s needs first.”

Her readers and fans appreciate Medina’s honest look at life and the realness of her characters and stories. But there are those who do not appreciate Medina’s candor. In fact, her book Yaqui Delgado Wants to Kick Your Ass (Candlewick, 2013) has been banned from some schools due to the “a” word in the title, and she has been uninvited from school visits. “I’ve been disinvited to events,” acknowledges Medina. “My book has been challenged. I’ve been called crass and ‘bad for children.’ One parent came on my website: ‘What’s wrong with you?’ she wrote. ‘These are children!’”

The Life-Altering Impact of Educators

“A kid’s life is filled with adults, some of them helpful, some not. Two teachers really stand out to me from my life. One was Mrs. Zuckerman, who was my third-grade teacher, and the person who first told me that I was a good writer. I was notoriously fidgety as a student. I’m sure I was a trial to have in class some days. But Mrs. Zuckerman had a way of loving all of us and making it safe to be ourselves in every way. To this day, I remember reading a poem about pollution to our class and her pretty handwriting at the top of my paper telling me that it was good. I wrote about Mrs. Zuckerman, in fact, in Been There, Done That: School Dazed (Grosset & Dunlap, 2016), an anthology edited by Mike Winchell. The piece is about how my mother made me give her a pair of pantyhose for her Christmas present that year.

“The second teacher was much later, in college. He was named Geoffrey Sommerfield, I think. He told me I didn’t have to be Picasso to be a worthy artist. He told me that I had a voice as a writer; I could find a channel that would suit my skills and interests and go from there. The thought had never occurred to me. But it gave me permission to think of writing as more than the classics I was reading in college. It opened an idea inside of me.”

Just like anyone else, Medina is not a fan of being rejected. But she is quick to point out that Yaqui continues to be one of her most popular books because it identifies an important but ugly reality of school life for many kids. “It has found a way to reach readers who most need the story,” says Medina, “and I’m grateful for that. I make no apologies for the language.”

“Almost every book I’ve written bears the emotional truth of my experience growing up a U.S.-based Latina.”

So what comes next for this Cuban American, award-winning author? According to Medina, she has a YA novel on contract with Candlewick, and a surprise project that should be announced shortly. She also suspects readers will see more of Merci Suárez.

For someone who never aspired to be a writer and who never dreamed being a Latina author was even possible, Medina has quickly become a fan favorite and a role model for young readers and new authors. “When all is said and done, I want readers to think of a Meg Medina book as something that contained wisdom and love in the pages. I want teachers and librarians to remember me as an author who wanted to embrace all people through story. I want my colleagues to remember me as a person who helped prop open the door for the many talented new voices who were coming behind.”