“Being a published author is something I wanted since I was a kid,” shares award-winning author Alan Gratz. However, it took the birth of his own child to make that desire a reality.

“I was just a couple of years into a career as an eighth-grade English teacher when my daughter was born. My wife and I both had full-time jobs, and we were trying to decide if we were going to send our daughter off to daycare or if one of us was going to stay home to take care of her. My wife, in words that will live in infamy in my household, said, ‘Alan, you’ve wanted to be a writer since you were a kid. You’ve been working on books on your weekends and your summers home. Why don’t you quit your job, stay home, and be a stay-at-home dad and a full-time writer?’ So I did.”

Alan Gratz as a little kid, watching television

Gratz took advantage of his daughter’s nap times and times when his wife, Wendi, could care for her to write, and write, and write. Though he had been writing prior to becoming a father, and had even submitted two manuscripts, he had received nothing but rejections. However, he didn’t let that stop him. “I just wasn’t willing to take ‘no’ for an answer. Every ‘no’ was just a message that, to my mind, said, ‘You’re not good enough yet. Keep trying.’ With each new book I wrote, I got better, and all the while I was going to writer conferences and reading books about writing and taking classes. I was always working on getting better, until I was good enough to be published.”

“As a boy I was a reluctant reader. Which is weird, because I read well and loved stories. But it took a really exciting book to make me sit still and read it. But I would sit for hours and play video games and watch TV and movies. Those things were just offering me stories in a more dynamic way than most books I picked up. So that’s the kind of book I’m trying to write today—the kind of book that can compete with a video game or a TV show or a movie. That’s the kind of book I longed to find as a boy.”

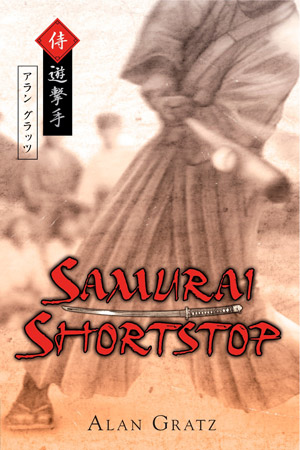

His drive and tenacity paid off once his daughter was born. “The very first book I wrote while I was a stay-at-home dad was Samurai Shortstop (Dial, 2006), which I sold before my daughter turned one year old. It was picked up out of the slush pile at Dial Books for Young Readers, an imprint at Penguin, and I got a phone call with an offer instead of a rejection. But that was the sixteenth publisher to see that book! The previous fifteen had all turned me down. And I’ve been incredibly lucky to be a full-time writer ever since.”

Alan Gratz home office

“Middle-grade readers love verisimilitude, and I shoot for that with every historical novel I write. I want it to feel real. Sometimes that means writing about some pretty tough topics and some hard scenes, but middle-grade readers respect that too.”

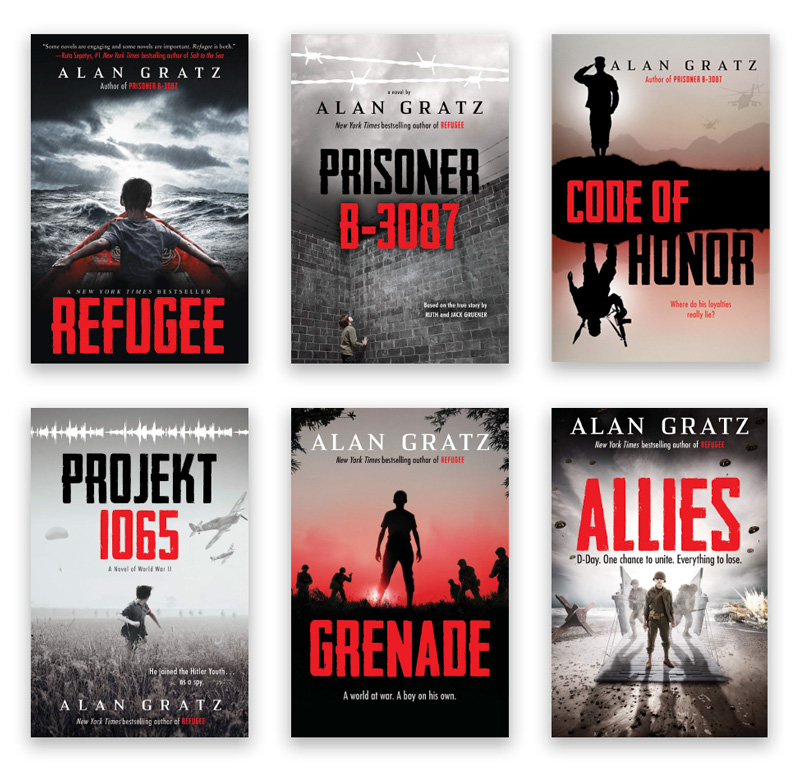

Since being published, Gratz’s work has met with critical acclaim. His books receive awards, make recommended lists, and become bestsellers. They are also on the best-of lists of many young readers. “I was very lucky that my first book, Samurai Shortstop, was named a Top Ten Book of the Year by ALA in 2007, which got my career off to a great start both on the trade side and the school and library side. The Brooklyn Nine (Dial, 2009) is another early book I wrote for Penguin that made a number of state lists and has been used in a lot of classrooms. But it was really with the publication of Prisoner B-3087 (Scholastic, 2013) that I began to have a real following among young readers—where they began to read books because they had my name on them, not just because the story sounded interesting.”

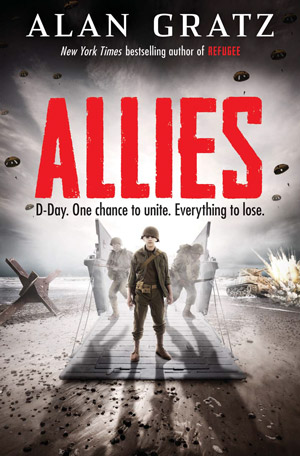

This year his fans are in for a real treat as Gratz’s latest novel, Allies (Scholastic, October 2019), is being published in honor of the 75th anniversary of D-Day. It is not the first World War II book he has written, but it is unique in its format—it features the stories and perspectives of several characters instead of just one.

This year his fans are in for a real treat as Gratz’s latest novel, Allies (Scholastic, October 2019), is being published in honor of the 75th anniversary of D-Day. It is not the first World War II book he has written, but it is unique in its format—it features the stories and perspectives of several characters instead of just one.

“Going into the project, I knew that D-Day was an operation of unprecedented cooperation, and I wanted to focus on that. That unity had to be central to the story. And the best way to show that, I thought, would be to not just tell one person’s story, but to tell many people’s stories on that day, to highlight the way so many people came together to stand against evil and make the day—and the war—a success. We live in a world of increasing polarization—at home and internationally—and I think the only way forward for us as human beings is to work together. If this book can help reinforce that message with young readers, then I will have done my job!”

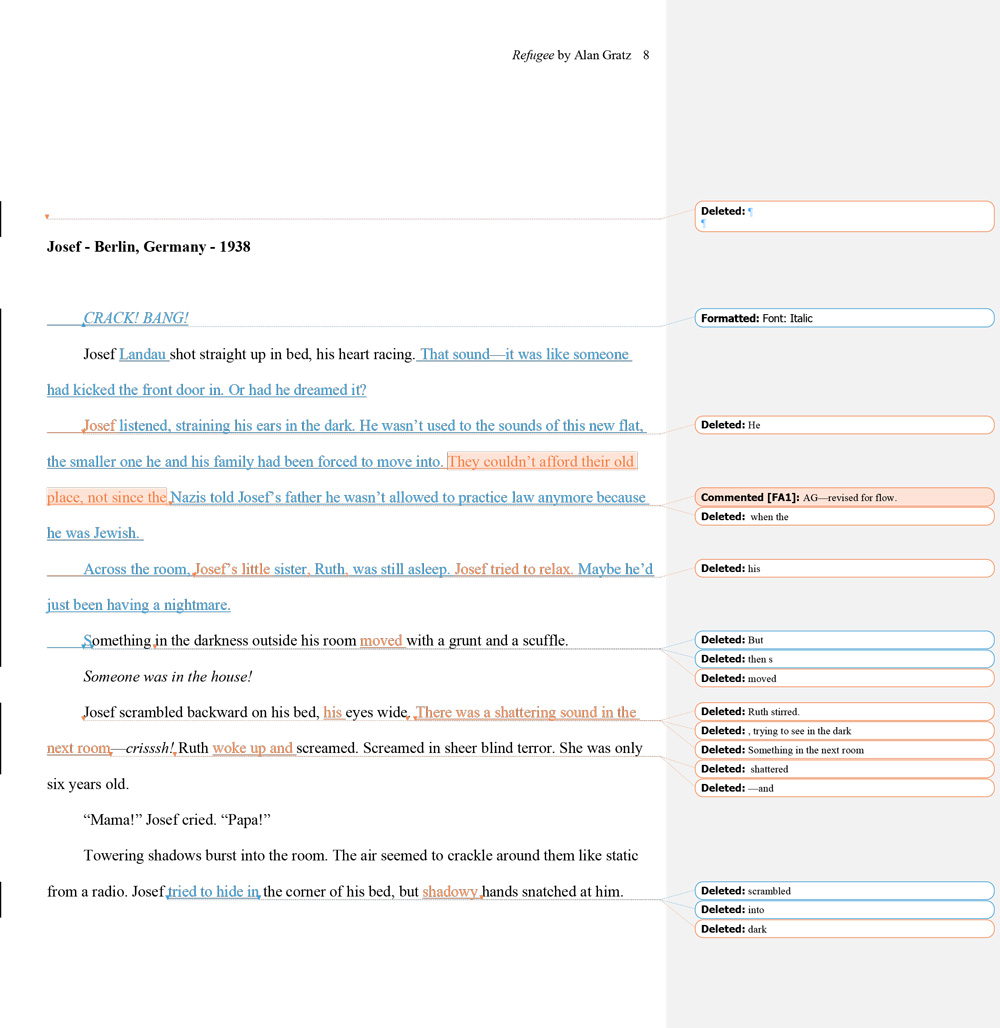

First page edits from Alan Gratz’s book, Refugee

Though Gratz does not overtly write morals and messages into his books, he does have hopes for how young readers will respond to his work. “The biggest thing I’m trying to do with my books is to help young readers understand how other kids live—their hopes, their struggles, and their motives—so that the readers see them as human beings, not statistics or sound bites.”

“All readers want books that grab them by the shirt and pull them along. All young readers want compelling stories with characters they care about. That’s what I’m writing. I’m glad my books appeal to readers of all genders and ages!”

He has seen teachers and librarians who also embrace his hope to build empathy and have used his books to do so. “I’ve seen teachers using my books in amazing ways. Timelines are always great ways to understand historical context—I’ve seen schools run butcher paper along a hallway, and kids fill in not only events from the book they’re reading but also other major events from the time. Many teachers will map the journeys of my characters to better understand the geography of our past and present. And, of course, reading and writing from the viewpoint of my characters builds empathy.”

Alan Gratz speaking to students at Hastings Middle School

Alan Gratz speaking to students at New Providence Middle School

Currently, Gratz is working on a new novel about 9/11 that is scheduled for publication in 2021—the 20th anniversary of that horrific day. “Middle schoolers today were born after 9/11, so for them it’s as much a part of history as D-Day.”

“’We are stronger together’ is the central theme of Allies, and what I most hope young readers take away from it.”

“I have young readers eagerly anticipating whatever is next for me, and they want it to be as good—or better—than the last! I enjoy that challenge. It pushes me as a writer. It makes me introspective as well. I hope my books make the world a better place to live in, whether it’s because they are entertaining and make someone’s time here on Earth more enjoyable, or because they touch someone’s heart and mind and make them want to work for positive change. Hopefully both.”

The Evolution of a Writer and His Writing Process

“If you went back in time and told college-writer-me that one day I would be known for writing historical fiction, he would have laughed you right back into your time machine. I was a lazy writer. What I mean is that I didn’t want to do research, I didn’t want to outline, I didn’t want to revise. I wanted to just rely on my own talent and just sit down and write something good. And I could do that! But what I realized, eventually, was that I wasn’t writing anything great. For that, I was really going to have to put in the time and effort on the front end and the back end of writing.

So how did I stumble into writing historical fiction? Samurai Shortstop. My first two attempts at writing a novel—both pretty lazy, by my earlier definition!—were contemporary stories that I didn’t have to research, hadn’t outlined, and had only revised enough to polish. Then, while reading a travel guide to Japan and thinking wistfully of finally getting to travel there, I ran into a story about the roots of Japanese baseball at the end of what was the country’s samurai era. There really had been people running around with samurai swords and baseball bats? What a great novel that would make!

So how did I stumble into writing historical fiction? Samurai Shortstop. My first two attempts at writing a novel—both pretty lazy, by my earlier definition!—were contemporary stories that I didn’t have to research, hadn’t outlined, and had only revised enough to polish. Then, while reading a travel guide to Japan and thinking wistfully of finally getting to travel there, I ran into a story about the roots of Japanese baseball at the end of what was the country’s samurai era. There really had been people running around with samurai swords and baseball bats? What a great novel that would make!

But I didn’t write historical fiction. I didn’t even know how you started to do that. But the idea kept calling to me, and so I jumped in. Along the way, I learned how to organize my research, to outline my story, and to really revise. Then, lo and behold, that was the book that got my foot in the door to publishing. From that point on I was a changed writer—and I had caught the historical fiction bug for good.

I know that many writers go to the locations they’re going to write about, and seek out primary documents to help bring their story to life in their heads and on the page, but that’s not how I work. I’ve never been to a place I’m writing about before I write about it, though a few times now I’ve been able to travel to a place I’ve already written about. I check out stacks of books from the library, and use other people’s research and accounts of a time and place to build my narratives.

How do I decide which bits to include? I’m always looking for the most interesting and most exciting bits! I have to be very careful not to exoticize—that’s not my goal. Instead, I’m looking for those parts of a time and a place that most of us don’t know about, but that really happened— baseball-playing samurai, Irish spies in Germany during World War II, Okinawan refugees on their own island during the Battle of Okinawa, Jewish prisoners who survived multiple camps during the Holocaust, modern-day refugees using Google Maps to work their way from Syria to Germany. I’m looking for stories and events that make you say, ‘Wow, I never knew that—but it really happened!’

I start with the kernel of an idea—an Irish spy in the Hitler Youth, three families escaping violence to seek new homes as refugees, multiple perspectives on the same massive D-Day invasion—and then research to support that idea. If the research doesn’t fit, I don’t force it!

For Allies, I had expected to write a book that was essentially like passing a baton, or a string of dominoes. I wanted one character to do something heroic, meet the next character, and then send him or her on their way, then do that all over again until the end. But that’s not really what D-Day was like. Many people were working in concert, yes, but often simultaneously, and spread out over a large area. So my domino idea went out the window! Instead, I found other ways to connect the characters.

For Allies, I had expected to write a book that was essentially like passing a baton, or a string of dominoes. I wanted one character to do something heroic, meet the next character, and then send him or her on their way, then do that all over again until the end. But that’s not really what D-Day was like. Many people were working in concert, yes, but often simultaneously, and spread out over a large area. So my domino idea went out the window! Instead, I found other ways to connect the characters.

Once I have enough story pieces that are supported by research, I outline the story on note cards on a big board I have in my office. When the outline is finished, I take the cards down, type them up, and begin to move the relevant research into the outline so I can have it at my fingertips when I write. Then I write a first draft, and revise that first draft. Then the book goes off to my editor, and she reads it and gives me notes. Then it’s back to revision! Revising is the longest part of the process—my editor and I will go back and forth on a book for almost a year until it’s ready.”