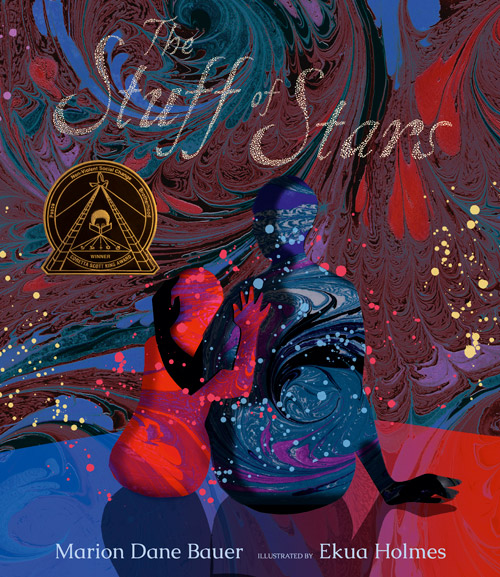

The Stuff of Stars (Candlewick Press, 2018). The title of this picture book sounds so esoteric. Is it about evolution? Astronomy? Life? Actually it is about all of that. And it all began not with a big bang, but with a quiet thought.

“The Stuff of Stars came out of a very specific place,” shares Newbery Honor author Marion Dane Bauer. “Years ago I attended a program at my Unitarian Universalist church by Michael Dowd and Connie Barlow. They talked about the origins of the universe and, in that framework, not just the inevitability but the necessity, even the gift of death. Stars died, and their deaths created planets. Dinosaurs died, making room for us humans. And I went away feeling deeply moved and somehow safe. I knew as I listened that I wanted to take this perspective to the very young. I didn’t know how to begin, though, so I set the thought aside for a long time.”

“The Stuff of Stars came out of a very specific place,” shares Newbery Honor author Marion Dane Bauer. “Years ago I attended a program at my Unitarian Universalist church by Michael Dowd and Connie Barlow. They talked about the origins of the universe and, in that framework, not just the inevitability but the necessity, even the gift of death. Stars died, and their deaths created planets. Dinosaurs died, making room for us humans. And I went away feeling deeply moved and somehow safe. I knew as I listened that I wanted to take this perspective to the very young. I didn’t know how to begin, though, so I set the thought aside for a long time.”

Eventually, Bauer reexamined her ideas of how the beginnings and endings of stars and life are all interconnected. “I began to do my own research about the way our universe came into being. When I’m studying a new topic in order to be able to write it for the young, I have to read and read and read until I understand deeply enough to be able to reach back into what I know and find a core that I can present with utter simplicity. That’s how I began. When I finally understood, I sat down to write.”

She formed each word and phrase to reflect the awe and reverence she feels for life, and for how the beginning of the universe and the planet Earth both connect to the beginning of a child. A far stretch for some, but not for Bauer. “As to carrying the idea from the birth of the universe to the birth of the child receiving the book, that seemed inevitable to me. When I’m writing the text for a picture book, I often reach outward to a big idea and then inward to the child I’m holding in my heart. And no other topic I’ve ever taken on seemed a better fit for that two-way reach.”

“Being the author of The Stuff of Stars is like being the tail on a comet. What an incredible ride!”

— Marion Dane Bauer

As awe-inspiring as the sparse text is, the illustrations are an equal match. Using bold colors, hand-marbleized paper, and digital collage, Caldecott Honor artist Ekua Holmes matched each page’s text with stunning illustrations. “I wasn’t originally sure if I was the right illustrator for the project,” says Holmes, “but I do love a challenge, and I decided to take it on. It took me a while to figure out how exactly I was going to deal with the subject, and believe me, I have a lot of failures on my studio floor; things that just didn’t work.”

Interior spread of The Stuff of Stars

Holmes finally found her spark of inspiration for the project in a scrap of marbleized paper. “I realized that I could show the depth and breadth and beauty and transformation of the universe through this technique. So I took some classes—I’d always wanted to do it, anyway—and those marbleized papers that I made became the foundation for the illustrations in The Stuff of Stars.”

Ekua Holmes’ studio

To create the mesmerizing illustrations, Holmes painted paper black and cut out basic shapes. She scanned them and then was able to cut and paste digitally. She also hand-marbled all the papers. “I had to go through the process of marbleizing and then look for the story in the papers. I am always looking for the story, for the characters and how they’ll be portrayed, whether in the colors I’m choosing or the techniques I’m choosing. The story doesn’t come (to me, at least) fully formed; it’s a process, it’s a dance. It’s an experience, and every book is its own universe.”

“The story doesn’t come to me fully formed; it’s a process, it’s a dance. It’s an experience, and every book is its own universe.”

— Ekua Holmes

When Bauer saw the universe of The Stuff of Stars that Holmes had created, she was thrilled. “Ekua was my first, truly my only choice, and her work is the most amazing gift to my words. I would have been heartbroken if she hadn’t agreed to take the manuscript on. But I knew I was handing any artist a unique challenge. When I write the text for a picture book, I am always very conscious of opening a window—a very large window—to illustrations. I never attempt to imagine those illustrations, because my imagination is not a visual one. The artist will do so much better than my imaginings. But when I wrote The Stuff of Stars, I knew I was opening a window into a vacuum. All that nothingness. All that listing of what is not yet there. And Ekua took the challenge and soared!”

“What do I hope my readers will take away from The Stuff of Stars? A deep sense of awe, of reverence toward this world we live in. A feeling of being profoundly loved. And even, probably on a more subliminal level, a first inkling of the place death has in making all life possible…and sacred.”

— Marion Dane Bauer

The positive reviews have also soared for The Stuff of Stars. In addition, it has received awards including the prestigious Coretta Scott King Illustrator Award. And educators are thrilled with the versatility of the book in their lessons, as well as the resources available. In addition to the resources available on Bauer’s website, “Bookology” magazine has published a Bookstorm which offers a downloadable bookmap and list of books, articles, websites, and videos to assist with incorporating The Stuff of Stars into curriculum. “And,” adds Bauer, “I would love to hear from teachers about any ideas they come up with for using The Stuff of Stars in their classrooms.”

The Evolution of an Author: Marion Dane Bauer

The Evolution of an Author: Marion Dane Bauer

I grew up in a home with books, and my parents were readers, but most of our children’s books came from my mother’s childhood home. That meant they were a generation or more older than I. Some are still well known: the novels of Louisa May Alcott and the verse of A. A. Milne. Alice in Wonderland (Macmillan, 1865), of course, and Through the Looking Glass (Macmillan, 1871), though I didn’t much like Alice. She always looked so cross in the illustrations! The Bobbsey twins, too, which others of my generation have read, but my Bobbsey twins wore knickers and high-button boots. Once my Sunday school teacher gave me a Nancy Drew novel. My mother was disdainful. No girl could run around doing the things Nancy did!

Marion Dane Bauer in 2nd grade

During my preschool years, my mother and I often visited our small town library. It was very limited, but I thought it a treasure trove. Nonetheless, every single time I came home with the same book. I don’t remember either author or title, but a fuzzy pink lamb leapt across a pale blue cover. The reading moment I remember comes from the time I was forced to bring a different book home from the library. I discovered to my horror that another child had taken my lamb book home. The book I chose instead, one both the librarian and my mother had to work hard to get me to accept, was small and fat and square with a sturdy, brightly colored, rebound cover. I was skeptical of its strangeness, but I sat on the couch and waited impatiently for my mother to come read it to me. Finally, in desperation, I opened the new book…and read it to myself! It was the first time I knew I could read! What a thrill! That was when I discovered that I could enter the world of books on my own. And I never stopped doing it!

When I must have been about ten or eleven I remember hearing something about “a writer” on the radio and saying to my brother, “I would never want to be a writer.” The reason? The unfriendly relationship I have to this day with a pen or pencil and a piece of paper. However, I was a storyteller. I carried stories in my head to be taken out during every quiet time. In high school I took a typing class, and learning to use a keyboard was like being given wings. From then on I knew I wanted to write, and I knew that I wanted to write stories.

I went to the University of Missouri to study journalism but discovered instantly that I hated it. So I turned to literature and philosophy instead. I even took a couple of creative writing classes, one in the short story. What stays with me from that time is a single paragraph I wrote in my spare time and showed to no one. It was a memory, a glimpse of being three or four years old, standing barefoot on a hot sidewalk in my backyard, then stepping off into the cool tickle of the grass.

After that year I went on to get married, to teach English, to have children. I continued to write, poems, long letters to friends, journal entries. Nothing meant for the market and certainly nothing that drew from that place that remembered the feeling of a hot sidewalk, the tickle of grass beneath my bare feet.

One day my daughter, my youngest child, began first grade. My then-husband chose that moment to say, “It would be awfully nice if you’d go back to work to earn some money.” So I said to him, “Give me five years to work seriously, professionally, full time at my writing. I’ll treat it like a job someone is paying me to do. And if in five years I can’t achieve something you and I can agree is success, I won’t give up writing, but I will go back to work.” He agreed, and I found myself in front of the 1956 manual, portable Smith Corona typewriter that had been my high school graduation gift in front of the blankest sheet of paper anyone has ever encountered.

I never considered any audience except children. That decision seemed to have been made when I wrote the small paragraph about a sunny sidewalk. And, in fact, I started with picture books. I began haunting the public library, bringing home armloads of books. While I was in the library, I wandered into the shelves for older readers. I discovered the contemporary juvenile novel; then I came across a shelf labeled Newbery Award. And I fell in love!

The two novels that moved me most deeply on that first exploration were William Armstrong’s Sounder (Harper & Row, 1969) and Paula Fox’s The Slave Dancer (Bradbury Press, 1973). It’s ironic that both exist under something of a cloud now, but what I discovered in each is still to be admired, a deep honesty in dealing with serious subjects. I came away from that reading understanding that I could write about anything that could impact a child’s life as long as I wrote genuinely and honestly. I wanted passionately to be a window into a more forthright, open world.

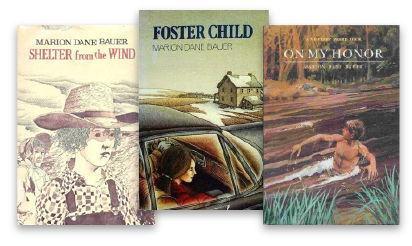

I had a foster child in my home that year, and I had strong feelings about the powerlessness of foster children. I [wrote] a novel called Foster Child (Dell Publishing Company, 1978). I found that a story about the abuse of religion was too hot a topic. So I went on to write a second novel, Shelter from the Wind (Clarion Books, 1976), this one less controversial, but still pretty hard hitting.

Then serendipity struck. (There is so much serendipity in any successful career.) I found Jim Giblin at Clarion Books, perhaps one of the few editors brave enough to consider a novel like Foster Child at all. He took on both at once. Shelter from the Wind came out in 1976. And Jim gave me permission to move into an even darker layer with Foster Child, a story of sexual abuse in the name of Jesus, that followed a year later. Which meant my first novel was published three-and-a-half years into my five-year test time and the second in four-and-a-half years. I still wasn’t bringing home much money, but there was no talk of my going “back to work.”

For the first fifteen years of my career I wrote only novels. On My Honor (Clarion, 1986) won a Newbery Honor Award. I have been a working writer for a long time. I feel incredibly fortunate to have been able for so many years to earn my living doing what I most love to do.

The Awakening of an Artist: Ekua Holmes

The Awakening of an Artist: Ekua Holmes

I began expressing myself through art at a very young age. Coloring books and crayons were a part of my early childhood education. I recognized that something happened while I was drawing that transported me into a peaceful calm space, and, as an only child, I had a lot of time to myself and a rich interior world.

I remember being excited about getting a paint-by-number set that my mother purchased for me. I remember smelling the oil paint and being excited to open up the little containers and match the numbers and watch the image —just a bunch of lines and numbers on a white canvas — transform into cockatoos or a forest or something like that.

Ekua Holmes with her dad

I was kind of an oddball in my family in that I was attracted to this art life, this interior life. And I was a collector of things that people throw away. I collected old jewelry and transformed it into new jewelry. If I saw a street sign down on the street, I’d try to drag it home and bring it into my bedroom. My mom allowed me to be me. My father died when I was about eight years old, and my mother just allowed me to be. We had a five-room apartment, and I was the polar opposite of my mother. She was very neat. She could tell if something was out of place from fifty feet away. She just allowed me to be myself.

My third-grade teacher, Mrs. Goldberg, told my mother that she should encourage me in the arts, and after that my mother starting taking me to Saturday classes at the Museum of Fine Arts. I remember walking up those big stairs and seeing the big ceiling and the paintings and just being in awe, and also having a great feeling that this was where I belonged. There was something about that place that was a part of me. Inside of my spirit I felt like this was where I needed to be.

My third-grade teacher, Mrs. Goldberg, told my mother that she should encourage me in the arts, and after that my mother starting taking me to Saturday classes at the Museum of Fine Arts. I remember walking up those big stairs and seeing the big ceiling and the paintings and just being in awe, and also having a great feeling that this was where I belonged. There was something about that place that was a part of me. Inside of my spirit I felt like this was where I needed to be.

I knew that I wanted to be an artist, but I didn’t know all that entailed. Over the years, I’ve learned that an artist wears many hats and needs more than just the skill of being able to make something two-dimensional look three-dimensional. Being an artist also has to do with having a deep reservoir of knowledge of history and humanity, and from that well you create.

I went on to a wonderful middle school with a great art department, and then on to a high school that had a great art department, but in college I kind of floundered when trying to figure out what my major should be. I was attracted to so many things that it was hard to pin down where I should put my attention

I had three different majors in college. The first was silversmithing — I was going to be a metalsmith and make jewelry, because we had that in high school and I enjoyed it. But I realized that wasn’t a good fit for me, so I moved over to an illustration major. I did that for about a year, but I felt like all the drawing was tedious, and I didn’t know if I was good enough at it. I’d always loved photography, but never thought about it as a major. I switched over and found my groove there and graduated with some honors. Photography has been a great teacher to me in terms of values and composition, and also as a way of engaging people to help tell a story.

After I graduated from college, I did photography around town. I did some weddings, some newspaper work, but it just wasn’t as satisfying as I thought it would be. I took a job in a city youth program, all the while with art percolating in my brain. I then became part of a company supporting another artist and ended up opening a gallery.

There were no galleries that represented black artists, and it was very hard to find imagery that reflected black lifestyles and black culture, so I began a business called the Great Black Art Collection. I created “home shows,” where I would basically turn someone’s house into a gallery and invite people in, and they would purchase.

I did get a later start being a professional artist. I was tinkering around with my own stuff, but not sharing with anyone, not showing anyone. At one point, I was putting together an exhibition of female artists and someone dropped out. There was all of this wall space that I couldn’t manage since I didn’t have artwork to put up. So I put up some of my own. They were little collages I had done around women and nature. I ended up selling all of those collages at that show. That made me stop and think: maybe I should put more time in on my own work. Fast-forward from there to an exhibition of my work at J. P. Licks, which is a very popular local ice-cream shop. A woman from Candlewick Press went in with her daughter to get an ice-cream cone and she saw my work, she saw something in my work, and she contacted me about doing children’s book illustration.

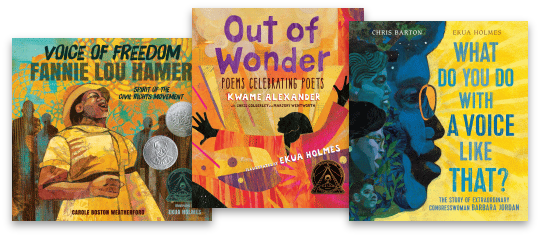

One of the biggest surprises from my first book, Voice of Freedom: Fannie Lou Hamer, Spirit of the Civil Rights Movement (Candlewick Press, 2015)was that it received so many prestigious awards. It was a perfect storm, really: a fantastic woman of power in Fannie Lou Hamer, a celebrated and prolific author in Carole Boston Weatherford, and then me. You have these three women coming together to tell a powerful story, and obviously it resonated with a lot of people, including the Caldecott committee and the Coretta Scott King committee. I was shocked that my first book was able to touch people in this way. It was a confirmation that I am on the right path and there is work for me to do on this path.

In addition to awards, one of the things that makes me feel really good about this work is my community and my family responding, encouraging me, supporting me, and celebrating the work that I have done. They are the people who have known me for the longest, have seen my struggles as an artist, and have seen my victories as an artist. I received an award from the Massachusetts branch of the National Council of Negro Women, and it was really special to look out in the audience and see some of my mother’s friends. They remember me when I was a little girl, how I loved to draw and make art and make jewelry, and they were there to see that play out in recent times. I also have a granddaughter named Song, eleven years old, and anything that makes her proud of me makes me proud of myself. When she says, “Nana, you are such a good artist,” that is like gold for me.