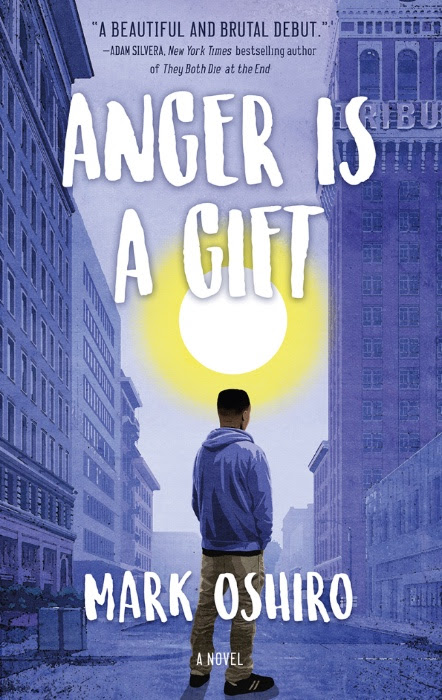

Mark Oshiro is making a name for himself. Already a well-known writer and media analyst for the Mark Does Stuff online community, he now has set himself apart from the crowd with his debut YA novel, Anger is a Gift (Tor Teen, 2018). Receiving rave reviews and being included on best-of lists, Anger is a Gift tackles not only love, loss, and resilience, but also police brutality, sexual orientation, and social justice. Here, Oshiro takes time to share about his roots and writing with eMackin readers.

Photo by Rakeem Cunningham

What was your childhood relationship to reading and books?

I have been a reader since I was very, very young. I read every book in my home by the time I was a teenager, and then tore through practically everything available to me at both my middle school library and the children’s section of my local branch. Most of the stuff my parents had at home was the classics of various genres: lots of Austen, lots of Edgar Allan Poe, Jack London, Dickens, and Bronte. It was educators—particularly the English teachers I had in high school—who opened my eyes to all of the books I’d been missing out on. Without them, I don’t know that I would have pursued a career in writing

Science fiction seems to be a genre that has captivated your attention. It is quite a departure from the classics that your parents had at home. How did you discover the genre?

I was lucky enough to be more or less raised on speculative fiction. Despite the fact that my parents were religious, they were still genre fans, so I grew up watching The X-Files and The Twilight Zone. We were a Star Wars household as well, so I was always looking to the stars, imagining what was out there, what sagas other worlds experienced. For me, science fiction is all about possibility, about creating worlds and imagining societies and technology, about thinking of the problems of our world and finding another means of addressing them.

In your author’s note in Anger is a Gift, you mention “fiction was my way of engaging with the outside world when I was growing up, but I desired so much more than what I had.” What do you mean by you desired more than what you had?

Although I grew up in a community that was mostly Latinx and Black, practically everything we were assigned to read was from white authors about white characters and white experiences. I wanted to write a book since I was a kid, but I didn’t think it was possible for a long time. Where were the authors like me, who lived lives like I lived my own? It wasn’t until my freshman English teacher assigned my class to read The House on Mango Street (Arte Publico Press, 1984) by Sandra Cisneros that I came to believe that I could actually write and publish a novel some day. From there, I discovered so many authors I had missed out on: Octavia Butler, Toni Morrison, Gabriel García Márquez, Alice Munro, and Isabel Allende.

Although I grew up in a community that was mostly Latinx and Black, practically everything we were assigned to read was from white authors about white characters and white experiences. I wanted to write a book since I was a kid, but I didn’t think it was possible for a long time. Where were the authors like me, who lived lives like I lived my own? It wasn’t until my freshman English teacher assigned my class to read The House on Mango Street (Arte Publico Press, 1984) by Sandra Cisneros that I came to believe that I could actually write and publish a novel some day. From there, I discovered so many authors I had missed out on: Octavia Butler, Toni Morrison, Gabriel García Márquez, Alice Munro, and Isabel Allende.

When and how did you finally venture into writing as a profession?

I tried to get into creative writing in college, and was certain that I’d study it there and become a novelist or a journalist all by the time I was 25. But college didn’t work out for me; the English department was too restrictive, and I felt like I was required to study people whose writing I did not enjoy. Also, it was just too expensive, and I ended up dropping out. I found my way back to writing through online journalism, and I started blogging again in the mid-2000s. I wrote for a community site that allowed me to do reviews of music and television, and that’s how I started the Mark Reads series back in 2009. So, I’ve been writing as part of a career since about 2007.

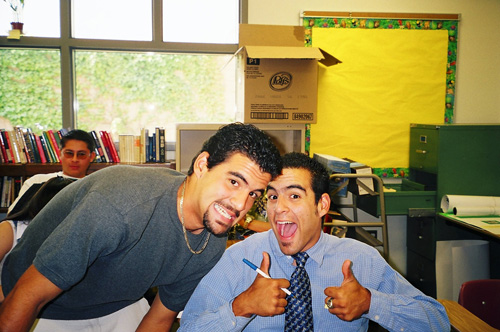

Oshiro with his twin brother in AP English class, 2001

Earlier this year your debut title, Anger is a Gift,was published as a stand-alone YA novel. Yet, it wasn’t your plan to write a stand-alone novel, was it? What caused you to change your plan for a science-fiction trilogy and make this a solo volume?

The primary impetus for changing the book’s plan was an agent I queried during the summer of 2016. He enjoyed the original story in Anger, but felt that I was juggling too many elements. There was a strong YA contemporary voice in the manuscript, and it was jammed inside of a science fiction framework. The advice I was given was to focus on one element, rather than both. It was an intimidating prospect, so I set out to rewrite the outline for the novel: one would be just contemporary, one would be only science fiction. I never made it to that sci-fi outline. Within days of starting it, I had a fully re-imagined story, and it just felt right.

Are you still planning to write a trilogy someday?

I would love to write a trilogy someday; it’s one of my favorite forms a story can exist in.

“When I was a teenager, I was lucky enough to have a few memorable educators—teachers, librarians, counselors—who supported me even if they didn’t necessarily understand me. That support was crucial to my growth.”

Let’s talk about your book for a bit. It is not just another YA novel filled with teen angst and emotions. Anger reflects a world in turmoil for teens—one in which police brutality isn’t something the characters just read about or hear about. Do you have personal experience with police brutality or with police presence on school campuses?

Both, actually. We had a resource officer on my high school campus, much like the character in Anger. And there are large portions of the book that are autobiographical. I have the same panic disorder as Moss due to an interaction I had with the police in 2008, and the lingering trauma was a huge inspiration for this novel. So, it was part therapy in a sense, as it was very freeing to be able to be honest and vulnerable about things I rarely talk about.

In addition to being therapeutic, why was it important to you to write this book? What do you hope readers take away?

On a personal level, I just needed to talk about what this experience is like. I didn’t realize how much I’d bottled up over the years. It’s been a humbling thing to hear reactions to the book that touch on this kind of honesty. I’ve had readers thank me for talking about grief, about trauma, in the way that I did because, just like me all those years ago, they didn’t know that they could be in a book. So I hope some people find themselves. I hope others widen their perspective. I hope that people feel more prepared to confront the reality of police brutality, to fight it in their own communities.

Oshiro with authors Zoraida Cordova and Daniel José Older at San Diego Comic-Con

I read that you are a social activist, and it seems that you are advocating student activism with your call to confront the issue of police brutality. What is your definition of a social activist? What do you do?

My activism has evolved over the years. Actually, because of the incident I referred to earlier, I have a difficult time attending protests, and it made me feel like a fraudulent activist for many years afterwards. I still do my best to attend protests or rallies when I can, but my activism takes many forms these days. I am vocal online about issues that are important to me and others; I help run workshops and panels to approach activism from the framework of education, particularly around issues like diversity in publishing/writing. I volunteer my time to help conventions create better, more inclusive communities. And I talk to kids.

When you talk to kids, what is your message? How can they make a difference? And how can educators respond to young people who want to be heard? How can they best support the right to expression even if they may not agree with the sentiments of the message?

When I was a teenager, I was lucky enough to have a few memorable educators—teachers, librarians, counselors—who supported me even if they didn’t necessarily understand me. That support was crucial to my growth. They listened to me. They validated my anger and let me feel what I wanted without shutting it down. And they believed me. I think that’s the most crucial element of it all, and what I hope Anger Is A Gift distills in others. I want kids to be believed when they see injustice in their communities, rather than condescended to, or being told that they’re too young to understand the world. That sort of response kills their sense of wonder, their sense that they can do anything about it all. And I’m speaking from experience, because while I had some great educators on my side, there were many in my high school’s administration who were absolutely not on my side or the side of the other teenagers. Believe them. It’s the best advice I can give.

“It wasn’t until my freshman English teacher assigned my class to read The House on Mango Street (Arte Publico Press, 1984) by Sandra Cisneros that I came to believe that I could actually write and publish a novel some day.”

Your book features diversity front and center, going beyond ethnicity and culture but also including sexual orientation. As inclusion has become important in the literature world, have you seen a satisfying amount of LGBTQIA+ representation or do you feel there is still a long way to go?

You know, I don’t want to diminish the difficult journey we have ahead of us. There really does need to be a lot of work done within publishing and within the book community to bring us closer to a sense of justice for those of us shut out of all of this. Just in the past few years alone, I’ve been able to read, edit, and write stories that were unimaginable to me when I was a teenager. While I know it existed, I had no access to books about queer teens or Latinx teens or teenagers with mental illnesses. I think about what kids have access to these days, and I’m hopeful. It’s not that there’s a satisfying amount of representation. We always need more because there are so many people who still cannot find themselves in novels. It’s that it finally feels truly possible; that we’re moving in a direction that will shake up the entire industry. And in the end, that will save lives. That’s what I’m concerned with.

So what are you working on next? What can readers look forward to seeing from you soon?

My second book with Tor Teen is out next year, and it’s truly the book of my dreams. It’s a fantasy novel that works within the realm of magical realism, and it’s about one teenage girl’s quest to defy the lonely, isolating role she has been given in her insular community. She makes a decision that has instant, horrifying ramifications, and she decides to leave her village and venture out into the unknown desert. It’s creepy and weird, and I can’t wait for others to read it!