Few of us Books in Bloom bloggers remember the good old days of receiving letters—though this blogger, in particular, does not have as many warm memories of actually writing those letters! I especially remember checking out my college mailbox hoping for letters from family and friends. I was always particularly pleased when my dad wrote—which meant that he wrote a sentence of two on the order of “Hi! How are you? Not much to say here. Love, Dad” in the middle of my mom’s newsier letters.

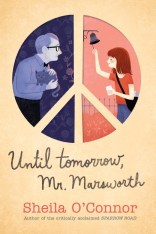

Sheila O’Connor shares how she was inspired to write her newest middle-grade book. Until Tomorrow, Mr. Marsworth, an epistolary novel, follows the communications between a young girl and her elderly neighbor in the late 1960s.

And check back tomorrow to enter a contest for Sheila’s books!

In 1968, I spent my days in the long silence of Sister Angela’s fourth-grade classroom. For a short stretch every afternoon, we sat in the warmth of winter sun streaming through the windows and disappeared into our books. I read many books that year, book after book from the low shelves of Resurrection’s library, but the book I loved the best was delivered by my classmate Georgia. I was the new girl in the classroom, attending my fourth school in as many years, and Georgia was a girl I barely knew. A tall girl who took dance class. A girl who lived on the north side of the creek in a neighborhood I hadn’t yet discovered. Still she gave me the great kindness of a book. It was old, with yellowed pages and a dull gray cover which meant the book was an antique, a keepsake, like the fancy crystal at my grandmother’s. It was a family book, she told me. A family book? We didn’t have books in my family, and I knew with those few words I was holding something special in my hands.

In 1968, I spent my days in the long silence of Sister Angela’s fourth-grade classroom. For a short stretch every afternoon, we sat in the warmth of winter sun streaming through the windows and disappeared into our books. I read many books that year, book after book from the low shelves of Resurrection’s library, but the book I loved the best was delivered by my classmate Georgia. I was the new girl in the classroom, attending my fourth school in as many years, and Georgia was a girl I barely knew. A tall girl who took dance class. A girl who lived on the north side of the creek in a neighborhood I hadn’t yet discovered. Still she gave me the great kindness of a book. It was old, with yellowed pages and a dull gray cover which meant the book was an antique, a keepsake, like the fancy crystal at my grandmother’s. It was a family book, she told me. A family book? We didn’t have books in my family, and I knew with those few words I was holding something special in my hands.

The book was Daddy Long Legs, written in 1921, by Jean Webster. An epistolary novel, it was told entirely in letters penned by a college girl named Judy and sent to her mysterious benefactor, a man she nicknamed Daddy Long Legs. It wasn’t a child’s book by any means, I know now it was considered a “college book,” but like many voracious readers in 1968, I read any book that landed in my hands. It’s safe to say, Daddy Long Legs was the book that made me fall in love with letters, the book that made me go on to write long missives of my own to friends from camp, and friends in far off places, and friends of friends who arrived as unofficial pen pals. This was a time without text or email, a time when long distance was expensive, and the letter was the way your life arrived in other worlds, and other worlds entered your existence.

The book was Daddy Long Legs, written in 1921, by Jean Webster. An epistolary novel, it was told entirely in letters penned by a college girl named Judy and sent to her mysterious benefactor, a man she nicknamed Daddy Long Legs. It wasn’t a child’s book by any means, I know now it was considered a “college book,” but like many voracious readers in 1968, I read any book that landed in my hands. It’s safe to say, Daddy Long Legs was the book that made me fall in love with letters, the book that made me go on to write long missives of my own to friends from camp, and friends in far off places, and friends of friends who arrived as unofficial pen pals. This was a time without text or email, a time when long distance was expensive, and the letter was the way your life arrived in other worlds, and other worlds entered your existence.

What I knew then, and know today, is that the letter is an incredibly powerful way to say what’s in your heart. It’s deliberate and thoughtful; it’s meant to enlighten or entertain. Depending on the receiver the writer’s truth is shaped or slanted. Affections are confessed. Secrets, too. Fears and worries shared. Things we can’t quite say face to face, find safety in a letter. In 1968, the letter had the power to build bridges, open doors, bring comfort, keep distant families close. And in that same year, in homes across the country letters arrived from sons and brothers and fathers and cousins and uncles and friends fighting in the war in Vietnam. And heartfelt letters from their home were written in return.

What I knew then, and know today, is that the letter is an incredibly powerful way to say what’s in your heart. It’s deliberate and thoughtful; it’s meant to enlighten or entertain. Depending on the receiver the writer’s truth is shaped or slanted. Affections are confessed. Secrets, too. Fears and worries shared. Things we can’t quite say face to face, find safety in a letter. In 1968, the letter had the power to build bridges, open doors, bring comfort, keep distant families close. And in that same year, in homes across the country letters arrived from sons and brothers and fathers and cousins and uncles and friends fighting in the war in Vietnam. And heartfelt letters from their home were written in return.

This is the world of Until Tomorrow, Mr. Marsworth, the world where eleven-year-old Reenie Kelly writes long, loquacious letters to her Army pen-pal Skip. It’s also the world where an eleven-year-old child becomes aware of the realities of war. Men are wounded. Skip’s best friend is killed. There’s homesickness and war sickness, and a wish for Reenie Kelly that she’ll know a better world.

Like that fourth-grade girl I was in 1968, Reenie Kelly also loves “the letter.” As she would say, she really, truly does. When she sets her pen-pal sights on her reclusive, outcast neighbor Mr. Marsworth, she has found in many ways the perfect receiver for her overflowing heart. Quiet. Patient. A man of so few words, Mr. Marsworth listens while Reenie Kelly writes. Leaving letter after letter in his milk box, Reenie tells the story of her family: their bankruptcy, her mother’s early death, her father’s job building roads in North Dakota, her rival brother Dare sleeping in the woods with his pup tent and his Sanka, and perhaps most importantly, she tells of her beloved oldest brother Billy, eighteen, and now in danger of the draft. For a young girl with a newly forming understanding of the realities of war—the Army pen pals killed, the bloody scenes of battles shown nightly on TV, the photos of the dead in Time and Life and Newsweek—the possibility of losing Billy to that war is too much for her to bear.

Like that fourth-grade girl I was in 1968, Reenie Kelly also loves “the letter.” As she would say, she really, truly does. When she sets her pen-pal sights on her reclusive, outcast neighbor Mr. Marsworth, she has found in many ways the perfect receiver for her overflowing heart. Quiet. Patient. A man of so few words, Mr. Marsworth listens while Reenie Kelly writes. Leaving letter after letter in his milk box, Reenie tells the story of her family: their bankruptcy, her mother’s early death, her father’s job building roads in North Dakota, her rival brother Dare sleeping in the woods with his pup tent and his Sanka, and perhaps most importantly, she tells of her beloved oldest brother Billy, eighteen, and now in danger of the draft. For a young girl with a newly forming understanding of the realities of war—the Army pen pals killed, the bloody scenes of battles shown nightly on TV, the photos of the dead in Time and Life and Newsweek—the possibility of losing Billy to that war is too much for her to bear.

So instead she tells it all to Mr. Marsworth.

And in the course of all those letters they both learn lessons about peace, and friendship, and what it means to stand up for your beliefs even when you have to stand alone.

Maybe the letter is a lost art, but the power of the written word, of telling our stories to each other remains a sacred act. Reenie writes to Mr. Marsworth, and Mr. Marsworth answers, just as I spent all those years writing Reenie’s story to young readers, hoping in my full heart that there was someone who would listen in the world. And on a day I’m really lucky, one of those kind listeners, like Mr. Marsworth, decides to write me back.

A day much like today, when I opened up my mailbox to a beautiful, long letter from a stranger, a sixteen-year-old named Summer who wrote from Florida to tell me how Until Tomorrow, Mr. Marsworth touched her heart. Back in 1968, Summer’s grandfather was a Catholic just like Billy, a boy who knew he wouldn’t be “good in a war”,” a boy who could not fight or kill. Summer said reading my novel helped her understand how her grandfather and his family may have felt during that war. Best of all, Summer shared her own dream to be an author.

Just as I once dreamed I’d write my own Daddy Long Legs someday when I was grown, Summer dreams now of her own book.

Just as I now dream that readers coming to the close of Until Tomorrow, Mr. Marsworth, will pick up a pen and paper and write a letter from their heart. A letter to a friend or stranger, or some family far away, a letter to the president or mayor, a letter to the newspaper. And I hope like Reenie Kelly they’ll discover how the letter can help to build a better world.

Books written by Sheila O’Connor:

Until Tomorrow, Mr. Marsworth. 9780399161933. 2018. Gr 5-7.

Keeping Safe the Stars. 9780142427583. 2012. Gr 5-8.

Sparrow Road. 9780142421369. 2011. Gr 5-7.

And if you want to check out her adult title:

Where No Gods Came. 9780472030514. 2001. Gr 10-Adult.

_________________________________________________________________________

Author biography:

Sheila O’Connor writes books for readers of all ages. Her most recent book, Until Tomorrow, Mr. Marsworth, is set in the summer of 1968, a tumultuous season she remembers well. Sheila’s faith in young people– their good hearts, their intelligence, and their ability to change the world—is what keeps her returning to the page. In summer months, she can be found writing in her little backyard cottage with her dog asleep beside her. Her book Sparrow Road won the International Reading Award; her second novel Keeping Safe the Stars was selected for the Midwest Booksellers Award. They have both been on “Best Books of the Year” lists. In addition to her work as a writer, she has taught writing to thousands of young people as a Writer-in-the-Schools. She also teaches at Hamline University where she is a professor in the Creative Writing Program and fiction editor for Water~Stone Review.

Sheila O’Connor writes books for readers of all ages. Her most recent book, Until Tomorrow, Mr. Marsworth, is set in the summer of 1968, a tumultuous season she remembers well. Sheila’s faith in young people– their good hearts, their intelligence, and their ability to change the world—is what keeps her returning to the page. In summer months, she can be found writing in her little backyard cottage with her dog asleep beside her. Her book Sparrow Road won the International Reading Award; her second novel Keeping Safe the Stars was selected for the Midwest Booksellers Award. They have both been on “Best Books of the Year” lists. In addition to her work as a writer, she has taught writing to thousands of young people as a Writer-in-the-Schools. She also teaches at Hamline University where she is a professor in the Creative Writing Program and fiction editor for Water~Stone Review.