When he was 19, my grandpa Bernard Wevers came to the United States from the Netherlands with his older brother, hoping to find a brighter future. He settled in a little town called Baldwin, Wisconsin, and married Wilhelmina, a daughter of immigrants herself. Some of his fifth-generation descendants still live in Baldwin.

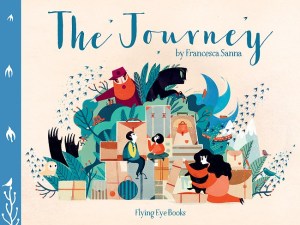

Grandpa Wevers left his home in Europe because he faced a bleak and uncertain future there, but he was fortunate in that the only thing he fled was poverty. Francesca Sanna’s recent book, The Journey, recounts the story of a family who fled their home because of terrible circumstances. Their story is far too common around the world today. And while my grandfather’s story had a happy ending, the tales of most refugees who are trying to escape violence and disaster do not have the same fate. Francesca’s book and her post raise the question: What should we be doing to ensure more bright futures for these victims?

_______________________________________________________________________

“Is your book fiction or nonfiction. Is this a real story?”

“Is your book fiction or nonfiction. Is this a real story?”

This was one of the first questions I was asked after the book was published, at one of the first Q&A I had the pleasure to attend in one of the many schools I have visited.

I remember that one of the first impressions I had when meeting readers around Europe, was that they learn about children’s books in different ways. English readers, for instance, even the very young ones, seem to distinguish very clearly between fiction and nonfiction literature, while in other countries this difference appears to be much less important.

So there I was, thinking about the story I wrote and illustrated and trying to explain to an eight-year-old how I like to think about my book as both fictional and non-fictional. Indeed it is a story which is based on, and combines, the real experiences of many people I have met, but at the same time, the story does not narrate the exact experience of any real person.

The Journey is the story of a family and of the journey they undertake when they realize their home is not a safe place anymore. As I briefly tried to explain in a note at the end of the book, it was inspired by many stories of many people I spoke with, from many different countries and backgrounds. A part of the research was even focused on historical documents about immigration in the early 1900s. I didn’t want The Journey to be a specific story, I wanted it to convey the idea that everyone has to right to have a safe place to live. For this reason, in the book, I try to give as little information as possible about where, or when, the story is set.

The Journey is the story of a family and of the journey they undertake when they realize their home is not a safe place anymore. As I briefly tried to explain in a note at the end of the book, it was inspired by many stories of many people I spoke with, from many different countries and backgrounds. A part of the research was even focused on historical documents about immigration in the early 1900s. I didn’t want The Journey to be a specific story, I wanted it to convey the idea that everyone has to right to have a safe place to live. For this reason, in the book, I try to give as little information as possible about where, or when, the story is set.

More recently during a reading with year two in a school in London, a boy asked me, “How do you end a book that is inspired by a real story if that story is still going on?”

Questions are always a challenge, and I love the process of thinking about them and

trying to come up with good answers—though I often fail,—but I found this one particularly interesting.

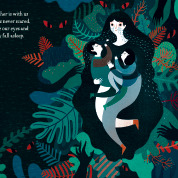

It made me think about another question I get quite often, mostly from adults: “Why does The Journey not have a proper ending?” The story I wrote does, in fact, have an ending, but it is a quite open one. The journey of the family we follow through the pages is not concluded in the usual way; the book ends leaving the family on their way to a new home, without showing any arrival. And this element was a very discussed one. Someone during a conference even told me I had cheated, I had gone against one of the main rules in children’s literature: a children’s book needs a happy ending.

A couple of years before I finished the book, I decided to do some research around the topic of immigration and in particular of refugees, because of what was happening (and sadly still is happening) in Italy, my home country, and in the rest of Europe. I was quite frustrated by having the same discussion over and over with people I knew, and by reading the comment sections of many posts on social media. In Italy the public opinion was – and still is – increasingly becoming more intolerant and turning against newcomers. When I first moved to study and work in other countries of Europe (Germany first and then Switzerland), I saw that the same discussion and attitude was spreading there too.

I finished the illustrations for The Journey in May 2015, right before one of the worst moments of the refugee crisis in Europe. After that, I was encouraged many times to change the ending of the story and to make the family finally arrive at their new home. I considered the idea and even tried some rough sketches of an ‘arrival’.

I finished the illustrations for The Journey in May 2015, right before one of the worst moments of the refugee crisis in Europe. After that, I was encouraged many times to change the ending of the story and to make the family finally arrive at their new home. I considered the idea and even tried some rough sketches of an ‘arrival’.

Finally, with the help of my publisher Flying Eye, I decided not to. Leaving the story open and the journey unfinished was the best way to start a discussion on this topic with the children through a proper tool, a book, that gave to this discussion all the time and space needed. In this way I could give an ending to a story that still does not have one, leaving it open.

After the book was published, The Journey had its own journey. I had the wonderful opportunity to meet an incredible community of librarians, teachers, activists, and most importantly readers. I went around schools in different countries (Spain, Austria, UK, Italy, Germany, and Switzerland) and saw the reaction to the book I wrote, discussing it with children and teachers.

After the book was published, The Journey had its own journey. I had the wonderful opportunity to meet an incredible community of librarians, teachers, activists, and most importantly readers. I went around schools in different countries (Spain, Austria, UK, Italy, Germany, and Switzerland) and saw the reaction to the book I wrote, discussing it with children and teachers.

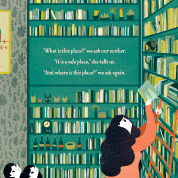

The reactions to my open-and-maybe-not-so-happy ending were varied, as were the general responses to the book in every class and every school. Sometimes, when I read the story, I would finish reading the last lines and then I would have to say “and this was the last page of the book”. Normally this moment is followed by surprised gazes and a few whispered “What???”. Some of the children like the idea of different possible ways of ending the story on their own, some other hate the concept of a journey that is not reaching the destination.

While at the beginning my idea of a blank ending was more a symbolic idea, to leave to parents or teachers the space for a discussion with their children about what happens next, I sometimes took it more literally, making workshops where children completed the story however they wanted. After I read the book, guiding them through some pages and explaining my choices for those pages, I first answer all the questions they have, page by page and then I ask them one question: How would you end the story?

While at the beginning my idea of a blank ending was more a symbolic idea, to leave to parents or teachers the space for a discussion with their children about what happens next, I sometimes took it more literally, making workshops where children completed the story however they wanted. After I read the book, guiding them through some pages and explaining my choices for those pages, I first answer all the questions they have, page by page and then I ask them one question: How would you end the story?