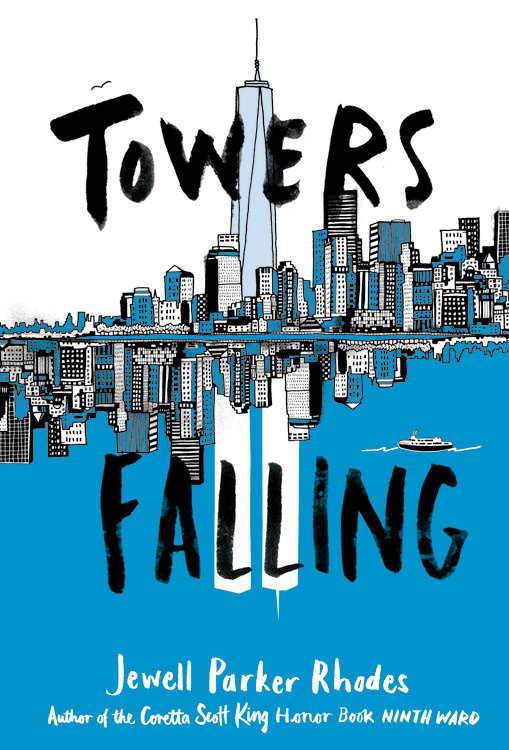

For those living when the Twin Towers fell, it was a day that will never be forgotten. Yet, as difficult as it may be to believe, there is now a generation that is unfamiliar with the horror and tragedy of that event. Award-winning author Jewell Parker Rhodes decided to address that lack of knowledge with her 2016 novel Towers Falling (Little, Brown Books for Young Readers). Here she discusses why she wrote the book and why she felt it was time.

“Kindness, compassion, empathy and joyful living honors all those who died.”

It has been 16 years since the Twin Towers fell, yet it still seems like a fresh wound for many. Do you remember where you were when you first heard about the horrific events of September 11?

When the Twin Towers were attacked, I was sleeping at home in Arizona. My husband woke me and the two of us were shocked and distraught watching the television images. I felt so vulnerable, sad, and outraged by the attack and the enormous loss of life. Months afterward, my depression still hadn’t lifted. Reading stories and viewing pictures of the victims who had all been unique, vibrant people with families, dreams, and hopes, made me feel an even greater obligation to live my life well. How dare I take living for granted? Kindness, compassion, empathy and joyful living honors all those who died. Writing diverse stories, teaching about humanity is an expression of my Americanness.

While some still are unready or unable to talk about the tragedy and trauma of that day, you chose to write Towers Falling. Why do you believe it is important to tell the story? Why tell it now? And why tell it through fiction to a middle-grade audience?

I think if I had witnessed the 9/11 horror firsthand, I may not have been able to write about it. When my editor suggested the subject, I immediately said, “No, no way. Too hard emotionally, too hard narratively.” Yet, for months afterward, I kept thinking about the children born post-9/11 who didn’t know how our country had been impacted and changed by that day.

It has always been my highest ambition to be a children’s author. I felt I had a responsibility to try and write a novel that wouldn’t patronize kids but would also serve as an antidote to Internet images that will forever show the towers being attacked and falling. Fiction and three-dimensional characters can express how friendship, family, love of country, and commitment to America’s founding principles can help move our nation forward.

I love fifth graders! In eight years these young people will be old enough to vote and defend our country. They need to know America’s history, past and recent. Because adults are traumatized by 9/11 memories, we have steered conversations away from this pain. But we need to be strong and engage children. Kids need to be nurtured and educated as citizens—the world depends on informed generations. Teachers are my heroes. I feel they are my secret weapon, the lead explorers helping to make 9/11 understood emotionally, historically, and intellectually for our youth.

“Kids need to be nurtured and educated as citizens—the world depends on informed generations. Teachers are my heroes. I feel they are my secret weapon, the lead explorers helping to make 9/11 understood emotionally, historically, and intellectually for our youth.”

Towers Falling has had an incredible reception. Readers rave about it, and the book has received numerous honors and awards in such a short time. What were your hopes for this book when writing it and when taking it through the publishing process? Did you expect this level of success?

I felt terrified, hurt, and challenged while writing Towers Falling. My editors, Alvina Ling and Allison Moore, were important touchstones. We all felt the obligation to get the story right. If I failed, we agreed, the novel would never be published. I also wanted to honor the multi-disciplinary teaching of P.S. 146. This school inspired me to write the story as recent history. The novel isn’t just about the day of the attack but about the response, the lessons to be learned, and how every American is connected to every other American. For me, teachers teaching my book is the highest honor. Visiting and Skyping with schools, [and] meeting Castleton Elementary students, teachers, and parents at the 9/11 Memorial are all heartfelt memories.

Towers Falling’s success helped me say “yes” to another hard project—the killing of young black children. Ghost Boys will be published in April 2018. I love all the books I’ve written for adults and children. But these last two novels—Towers Falling and Ghost Boys (Little, Brown Books for Young Readers)—felt more like a calling. An obligation.

In addition to September 11 and your Ghost Boys project, you have also written about Hurricane Katrina. What is it about these terrible events that draws your attention and makes you want to write?

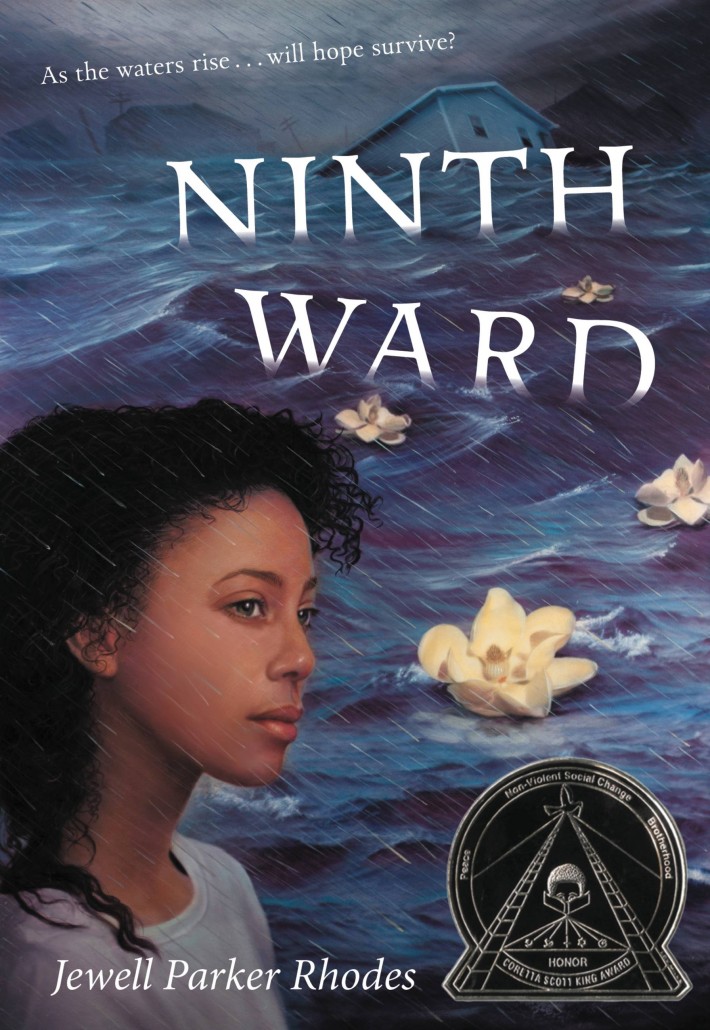

I love Louisiana—the people, the food, and the landscape. Ironically, the day Katrina hit, I was celebrating the publication of my Louisiana adult novel, Season(Washington Square Press, 2011). Two weeks later, my publisher sent me to New Orleans and I got to see some of the devastation firsthand. I immediately thought: What about the children?

My family experienced the 1994 Northridge Earthquake. Our two-year-old son stopped speaking, our five-year-old daughter trembled during aftershocks. Family love and warmth kept us all together. As adults, we sometimes discount how children have to be resilient during disasters, too. My love of Louisiana and my experience as a young mom merged. I was inspired to write my first children’s book. Smart, spiritual, and strong, my character, Lanesha in Ninth Ward (Little, Brown Books for Young Readers, 2010), heralds the glory I see in today’s children. As adults, we know bad things happen. Kids know it, too. I mirror for children how they are called upon to stand up, spread love, survive, and be resilient.

My family experienced the 1994 Northridge Earthquake. Our two-year-old son stopped speaking, our five-year-old daughter trembled during aftershocks. Family love and warmth kept us all together. As adults, we sometimes discount how children have to be resilient during disasters, too. My love of Louisiana and my experience as a young mom merged. I was inspired to write my first children’s book. Smart, spiritual, and strong, my character, Lanesha in Ninth Ward (Little, Brown Books for Young Readers, 2010), heralds the glory I see in today’s children. As adults, we know bad things happen. Kids know it, too. I mirror for children how they are called upon to stand up, spread love, survive, and be resilient.

In your books you seem to weave a lot of issues into the storylines. For example, in Towers Falling alone, I saw issues of diversity, racism, poverty and homelessness, terrorism, family relationships, and friendship. Is this something you intentionally do? Why?

Capturing the complexity of life has always been my goal as a novelist. I write in layers—one draft, then another, adding layer after layer to make what I hope will be a novel worthy of kids and for study in the classroom.

I’ve experienced many hardships—the worst of them happened during infancy, elementary, and middle school. Having said that, I did think Ninth Ward was a YA novel but my publisher convinced me I was writing middle grade. Certainly, I’m writing books I wish I could have read when I was a kid.

“School was where I soared…Librarians and teachers empowered me. Is it any wonder I became a professor?”

When you were a middle-grade young person, what were you reading and what issues were you facing? When you write to that age group now, are you writing from personal experience or writing to current issues and interests?

Thanks to school librarians and teachers, I read constantly as a child. Though there weren’t characters of color in my books, I, nonetheless, learned through character-driven fiction about empathy and common humanity.

My mother abandoned me as an infant and I was raised by my grandmother in an impoverished Pittsburgh neighborhood. I read Heidi (1881), Black Beauty (Jarrold & Sons, 1877), The Borrowers (J.M. Dent, 1952)—lots of classic stories. What I loved most were the Classics Illustrated comics. Books were too expensive to own but if I collected pop bottles and redeemed them for pennies, I could buy comics to keep. My favorite was about Prince Valiant. From this comic, I adopted a life mantra: “I want to be valiant. To live valiantly.”

My mother abandoned me as an infant and I was raised by my grandmother in an impoverished Pittsburgh neighborhood. I read Heidi (1881), Black Beauty (Jarrold & Sons, 1877), The Borrowers (J.M. Dent, 1952)—lots of classic stories. What I loved most were the Classics Illustrated comics. Books were too expensive to own but if I collected pop bottles and redeemed them for pennies, I could buy comics to keep. My favorite was about Prince Valiant. From this comic, I adopted a life mantra: “I want to be valiant. To live valiantly.”

I was a shy, sad child and when my mother returned for me at eight, my life went from bad to worse. By 14, my mother had kicked me out of her California home; by 15, I’d figured out how to graduate high school and leave my father’s and stepmother’s inhospitable home.

My books express some of my childhood struggles, but I try to stay aware of young people’s struggles today and I write for them, their future. I consciously honor children from diverse backgrounds. Not seeing myself in books, made me think only white people could write books! Celebrating uniqueness and common humanity is our key to the future.

While I felt isolated and lonely as a child, my characters are not based on me but inspired by the beauty I see in today’s youth. Perhaps it’s the teacher in me, the parent and grandmother in me, but I am very aware that the child today will shape tomorrow.

Because of my childhood, I think my skill as writer is, in fact, to write about the harshness of life. Embedded in my words though is the promise that I will guide the reader through the tale safely and soundly, and shower them with love and triumph.

With such a difficult childhood, where were you exposed to books and literacy on a regular basis?

School was where I soared. My grandmother never finished third grade; my parents never graduated high school. All my relatives struggled to make a living. Librarians and teachers empowered me. Is it any wonder I became a professor? “Teaching through dramatic stories” is how I write. Historical fiction offers a rich landscape to explore.

When did you know you wanted to be a writer? And when did you know you were a writer?

When did you know you wanted to be a writer? And when did you know you were a writer?

I always wrote stories, poems throughout my childhood. But it wasn’t until I was a junior in college that I realized black women wrote books. It was a revelation. I switched my major to English. It took 10 years to write my first adult novel, Voodoo Dreams (St. Martins Press, 1993). (Louisiana had already captured my imagination!) Finishing that novel made me feel successful. Writing helped me heal so many childhood wounds. I had survived. It took three years for Voodoo Dreams to be published, but I had already learned that it’s not publishing per se that matters. It matters more to accomplish what is meaningful and hard. It was this lesson that prepared me for writing Towers Falling and Ghost Boys. Yes, the stories are hard but worth being told and risking failure. I’m glad I wrote these two books, in particular, even though, at times, the psychic and emotional cost was high.

What are you working on currently and what can readers look forward to seeing from you soon?

Here is the description for Ghost Boys:

Twelve-year-old Jerome is shot by a police officer who mistakes his toy gun for a real

threat. As a ghost, he observes the devastation that’s been unleashed on his family and community in the wake of what they see as an unjust and brutal killing. Soon Jerome meets another ghost: Emmett Till, a boy from a very different time but similar circumstances. Emmett helps Jerome process what has happened, on a journey toward recognizing how historical racism may have led to the events that ended his life. Jerome also meets Sarah, the daughter of the police officer, who grapples with her father’s actions.

This story sounds bleak. But in a poem, the ghost boy, Jerome, writes:

Only the living can make

the world better.

Live and make it better.

Wow! It just occurred to me that this is my personal call—another way of expressing my desire to be “valiant.” Maybe this is why it took so long for me to fulfill my dream to be a children’s author? I had to survive my childhood pain. By living, loving, I’ve made my life better. My writing seeks to remind everyone—but especially children—that no matter how hard life seems to be, they can and should “live and make it better.”