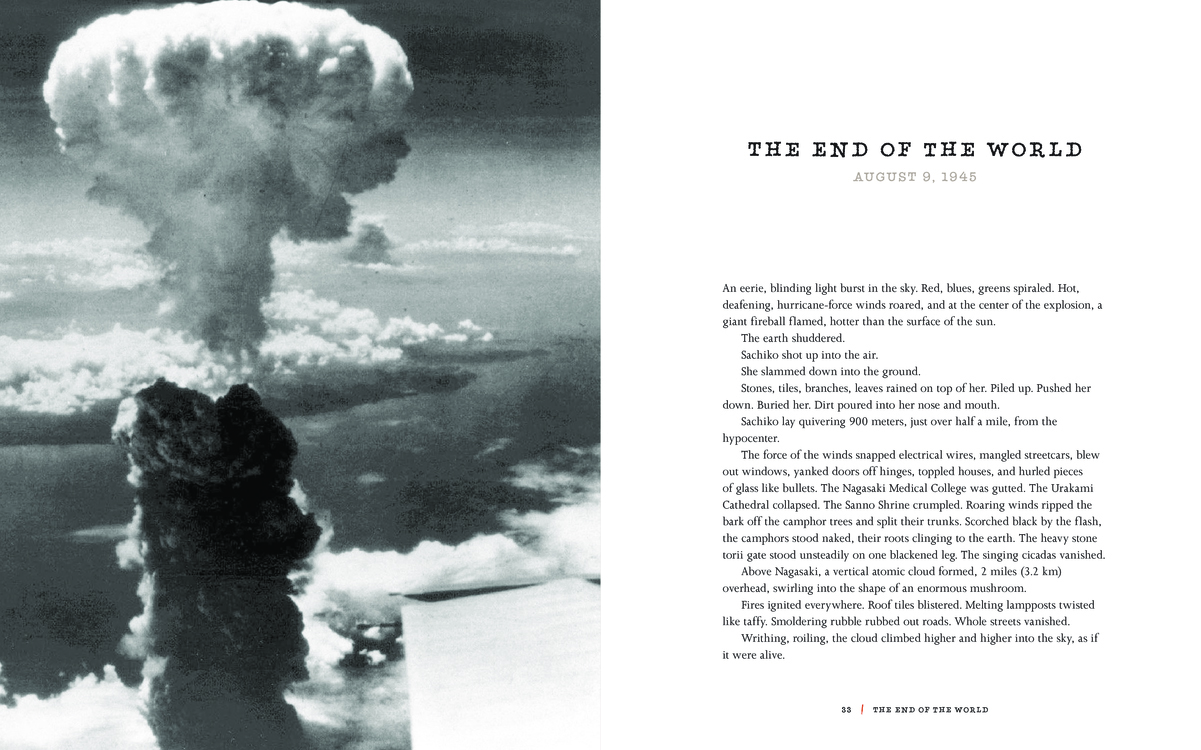

On August 9, 1945, six-year-old Sachiko Yasui was living in a world that was suffering the effects of World War II. But that morning was different. It was life-changing for Yasui. For on that day, an atomic bomb was dropped on her hometown of Nagasaki, Japan. Her family and friends died, and she was ostracized for being a bomb survivor.

On August 6, 2005, Caren Stelson was living in relative peace, though the world was filled with plenty of war and unrest. But that morning was different. It was life-changing for Stelson. For on that day, an atomic bomb survivor named Sachiko Yasui spoke at a ceremony in Minneapolis, Minnesota, commemorating the 60th anniversary of the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

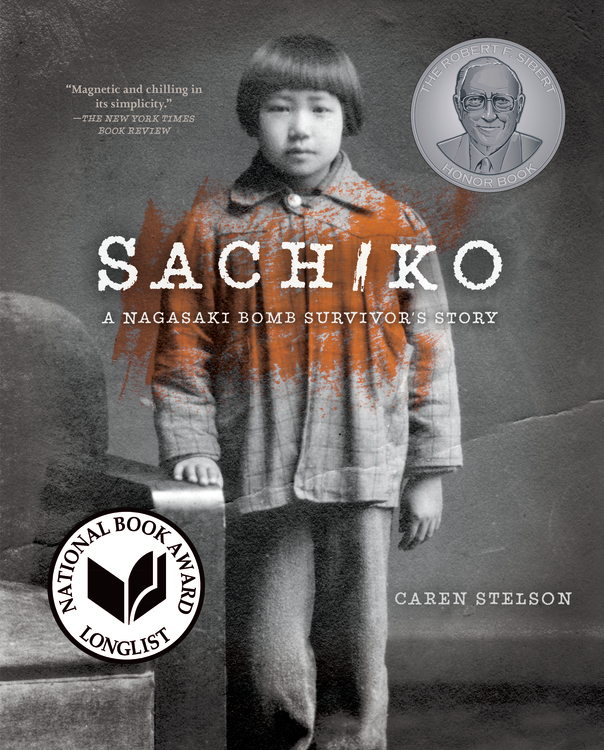

Eleven years later, Stelson’s factual account of Yasui’s experience, entitled Sachiko: A Nagasaki Bomb Survivor’s Story (Carolrhoda Books, 2016), was published. And since that day, many readers’ lives have been changed as they discover the horrors of war through this firsthand account, and learn how transformative messages of peace can be shared.

In less than a year, Stelson’s book has garnered fans from around the world. It has also been named a Minnesota Book Award Finalist, a Robert F. Sibert Informational Honor Book, and Sachiko received the 2017 Jane Addams Award for Older Children. Further, it was long-listed for the 2016 National Book Award for Young People’s Literature. Here, author Stelson shares her insights and experiences surrounding the writing and publishing of this timely nonfiction title.

It seems this book all started with your attendance at the WWII commemoration ceremony more than 10 years ago. Why were you at the event?

I can say that one of the beginnings of my Sachiko journey was at 8:00 am, August 6, 2005, at the Lyndale Park Peace Garden ceremony in Minneapolis. As other participants, I came to commemorate the 60th anniversary of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and the end of WWII.

That morning, my mind was not on Hiroshima; I was thinking about my father. At that time, I was deep into researching my father’s WWII military history. I thought I would be writing about him. My father was a highly decorated soldier. During the war, he was also a very young captain in the infantry, fighting his way through Germany.

As many veterans, my father rarely talked to his children about his war experiences. In May 2005, I went on a battlefield tour of Germany with surviving members of my father’s company, now old men, to listen to their stories and meet German veterans who had fought on the other side. At various points along the tour, German veterans welcomed us to their peace ceremonies. It was my first experience witnessing the power of peace and reconciliation between former enemies.

“Peace is not a noun. Peace is a verb. Peace is action. Peace takes courage.”

This battlefield tour could be considered a starting point for my Sachiko journey. But the year I lived in England (2001-02) could also be considered a starting point. That year I explored the art of oral history and interviewed British men and women who had as children of WWII survived wartime bombing. I wondered how the war impacted them as children and as they grew into adulthood.

Who carried hate, fear, and anger with them as they aged? Who internalized the experience of war and turned that experience into a force for good? How did and does this transformation happen? These questions were at the back of my mind at the Lyndale Peace Park on August 6, 2005.

When Sachiko was introduced, I realized her story may be the ultimate story I was searching for. I can still hear my thoughts whirling in my mind, “She survived the atomic bomb. How was that possible?”

Why did you believe Yasui’s story needed to be told more broadly through a book?

That’s an easy question to answer and a hard one. The easy answer is to say, I’m a writer and my mind goes to books. With little effort, I saw Sachiko’s story as a book. The harder question to answer is what possessed me to think I could write this book?

Although I had been immersed in the European theatre of WWII, I didn’t know that much about the war in the Pacific. Why? I’m a history major. Why didn’t I really know what happened to people who survived the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki?

As Americans, we’ve read about the experiences of those who survived the concentration camps in Europe. We know Anne Frank’s Holocaust story. What of Japan? Yes, we have Sadako’s story of her thousand paper cranes, a story from Hiroshima. But what child speaks for Nagasaki? More importantly, why as a nation, were we not more aware of the hard consequences of the decision to drop the atomic bombs, short term and long, given that our government was responsible for that decision? These became slow burning questions that kept growing hotter and hotter in my mind.

When did you decide to turn those questions into actions?

It took me five years before I decided to reach out to Sachiko and ask if we could work together to write her story for young people in the United States. By this time, I had finished a MFA in Writing for Children and Young Adults at Hamline University.

Caren presenting “Sachiko” to the mayor in Nagasaki along with Lerner employees and others involved in the book.

As a writer for young people, with my teaching experience, my work in school publishing, and my interviews and oral history experiences, I thought I had the ability to capture Sachiko’s story—perhaps even an obligation to bring this story to light. I had no idea how challenging writing this book would be. If someone had told me up front what it would take to write Sachiko and how long, I probably would have been too scared to try.

How did the process of writing this book affect you?

To write Sachiko’s story, I traveled to Nagasaki five times to walk through nuclear war with her. I imagined living in the aftermath. I had nightmares when I returned home. I interviewed other hibakusha, atomic bomb survivors, read as much as I could, both narratives and history from various perspectives, and discovered events more complicated, controversial, and painful than I had expected.

As we moved through Sachiko’s unfolding story, I found I needed to heal from the writing of this difficult story as Sachiko needed to heal from her experience. By following in Sachiko’s footsteps, I studied the works of Helen Keller, Gandhi, Martin Luther King, Jr., and other peacemakers; as I did, I found myself stronger, more resilient, and more focused on my own pathways to peace.

So in your search for personal healing and peace, did you find inspiration in the life or words of specific individuals?

We live in turbulent times. As an adolescent, I grew up in turbulent times—the Cold War, the Cuban Missile Crisis, assassinations, the civil rights movement, the marches against the Vietnam War. The world felt very unstable to me then, too.

Martin Luther King, Jr. was a great inspiration to me as a teenager as he was for Sachiko. I read or reread nearly all of King’s speeches as I worked on Sachiko. His words ring as true now as they did in the 1960s.

“Don’t lose sight of people who inspire you, and you won’t lose sight of the person you hope to become.”

Today, I am a great admirer of Congressman John Lewis. The award-winning March: Book 3 (Top Shelf Productions, 2016) captures Lewis’s bravery. His call for justice from the halls of Congress makes it clear that the work of peace and justice is never done. Lewis reminds us that peace is not a noun. Peace is a verb. Peace is action. Peace takes courage. Peace is sweat and effort to bring justice to our homes, neighborhood, country, world. As we know so well today, there is much more peace and justice work to do.

What advice or counsel do you have for those growing up now?

Several years ago, I came across a quote from Newbery Award-winning author Katherine Paterson. She wrote, “I was already wise by the time I was eleven. There was no way my parents could have protected me from the world as it was. I had already seen too much. What I needed was not an outer guard, but an inner strength. I needed to know one could endure the loss of paradise.”

Sooner or later, we realize we need the inner strength to become the person we want to be in the world. I would say to young people, develop your inner strength for the work ahead. Study. Read widely. (Ask your librarian to suggest titles of life-changing books.) Feed your curiosity. Test yourself. Open yourself to friendships. Reach out in service. Don’t lose sight of people who inspire you, and you won’t lose sight of the person you hope to become.

Since Sachiko was published, it has received numerous accolades including being long-listed for the prestigious National Book Award. Did you ever expect your book to receive this response?

I’ve been totally caught off guard by the awards and accolades given to Sachiko and totally humbled by all of them.

The publishing process with Carolrhoda/Lerner Publishing Group was so intense; I didn’t have time to think about what would happen once Sachiko stepped out into the world. What I learned was that an award-winning book happens when the editor and designer bring as much passion to a book as the author.

My fabulous editor Carol Hinz and I continued to refine the manuscript right up until the last moment. I had final discussions with Japanese history professors to check facts. I had last minute SKYPE phone calls to Sachiko in Nagasaki to verify small details. My Minneapolis translator, Keiko Kawakami, helped us with the Japanese glossary, a decision at the end of the process. All the while, insightful book designer Danielle Carnito worked to add the visual presentation to deepen the story.

When Sachiko was first published, my greatest hope was that the book would do justice to Sachiko’s life and my readers would draw strength and inspiration from her story. My second hope was to reawaken my readers to the existential danger of nuclear weapons. No one should forget the memory of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

What are you working on now and what can readers look forward to seeing from you soon?

I’ve been spending much of my time talking to schools and various groups about Sachiko. My audiences have been from ages 10 to 90. Grandmothers for Peace was as eager to hear about Sachiko’s story as were fifth graders.

I’ve also been volunteering for the nonprofit organization, World Citizen. World Citizen’s mission is to “empower communities to educate for a just and peaceful world.” I continue to support the Saint Paul-Nagasaki Sister City Committee, an organization crucial to my research in Nagasaki. I also created the Sachiko Scholarship for Peace with portions of the proceeds from the book to fund student exchanges between Minnesota and Nagasaki.

All these activities are gratifying, but I’m also eager to get back to my writing desk. Unfinished manuscripts are calling—and so is a brand new grandbaby in Boston.