This is super quick and a little sloppy, but super helpful. Sydnye Cohen and I started this system back in 2013-2014, and I thought someone else might find it useful. It is not tech-y or sexy. It’s pretty old school, but it is efficient.

Problem: You’ve promised a teacher who is struggling with mediocre researchers (75 students, 10th grade, social studies) to help her evaluate bibliographies and provide students with feedback BUT you’ve had a crazy week and you’ve been pulled in 17 different directions and here it is, Thursday evening at 8PM, and you need to be done by morning.

All nighter? No way. Those days are over for me.

Let’s just start with how we collected the assignment. The teacher’s plan was to have students print their bibliographies, bring them to my colleague Jackie or me, and have us “sign off” on those that “met goal”.We nixed that. It would have been a logistical nightmare – particularly given all those 17 directions I mentioned.

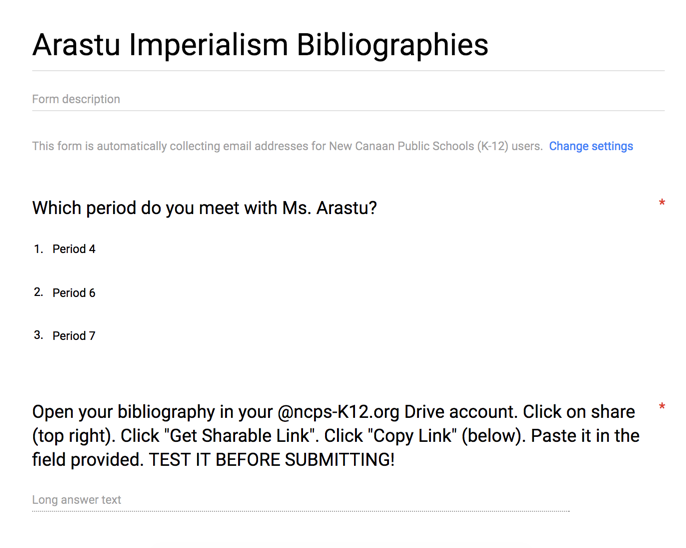

So we created a very simple Google Form for her. Literally, this is the form.

We sent students an email with a link to the form. The teacher gave students time in class to add their link to the form. You may have noticed that we did NOT ask students to give us editing rights. That was intentional. It takes too long. I don’t know about you, but if I have editing rights to 75 bibliographies, I am going to spend 8-10 hours correcting them. This was a self-preservation strategy.

So… using the student responses to the form, I now have a spreadsheet full of links to bibliographies. Cool. Well, not really, but let’s pretend.

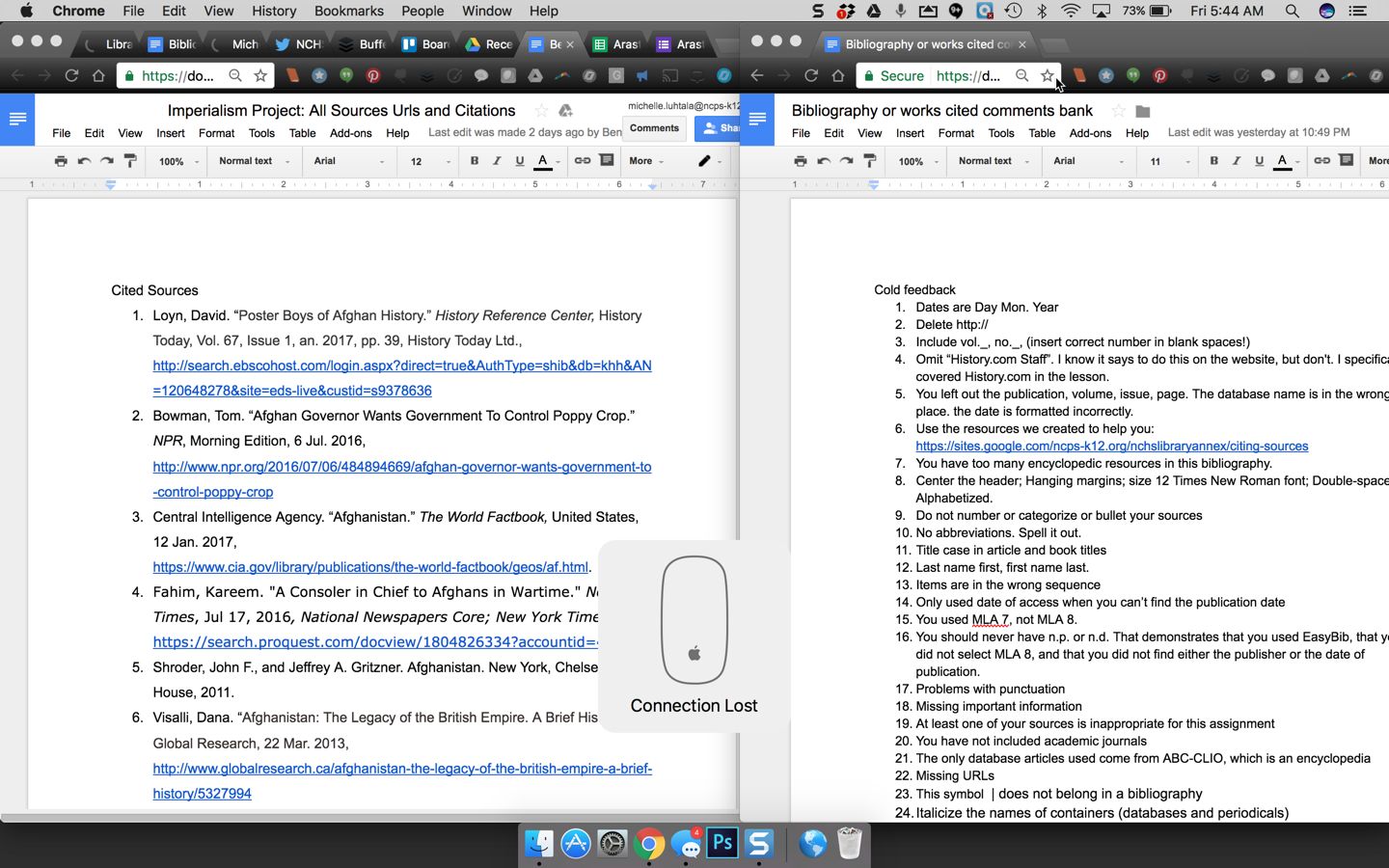

I split my screen into two browser windows. I open the spreadsheet on the left, and a blank document on the right. I spend some time on the first five works cited lists (to avoid redundancy, I will use the terms bibliography and works cited list interchangeably even though they are not interchangeable), typing into the blank sheet on the right all the comments I would have posted if I had editing rights to the bibliographies.

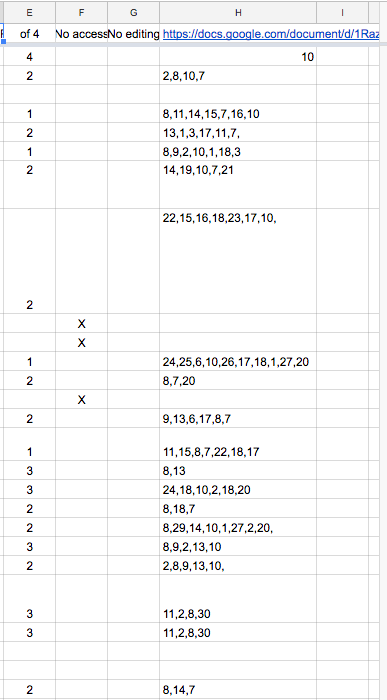

Then I use the “bullet” function to number them. Once I have the first 12 (or so) comments in the document on the right, I add a few columns to the right of the students’ links in the spreadsheet on the left. Now I go back and review the bibliographies I already looked over.

Using lined notebook paper, I note in one row all the numbers of “comments” that apply to that bibliography. For example, in the one above, I would indicate an 8 and a 9 without having to read a word, but I would add more as I scanned the entire work. I do not recommend going in order. Just jot down the numbers as you notice things. Also, don’t try to address everything. Hit the big things. The whole point of this exercise is to avoid getting bogged down by minutia (unfortunately the task itself is all minutia – therein lies the time-suck factor).

OK. I now enter the comment numbers into the column to the right of the link in the spreadsheet. Then I reflect on the comments and I assign the student work a holistic score on a 1-4 scale (this rubric needs an overhaul, but it was what I used – loosely). I add the score to one of the other columns to the right in the row with the link for that bibliography.

OK. I now enter the comment numbers into the column to the right of the link in the spreadsheet. Then I reflect on the comments and I assign the student work a holistic score on a 1-4 scale (this rubric needs an overhaul, but it was what I used – loosely). I add the score to one of the other columns to the right in the row with the link for that bibliography.

Then you hustle on through the rest of the bibliographies. It goes faster and faster, because you start to memorize the numbers as you revisit them. Before you know it, you have given 75 students comprehensive feedback, and a teacher a holistic score for each student. Everyone is happy. Well, the kids usually aren’t but hey, it’s school and we’re talking about bibliographies after all. You can hide the score column to preserve the students’ dignity or just make a copy of the spreadsheet, removing that column and share that with the students instead. There is instructional value in having all students see what comments other students receive. One in-class work day with this spreadsheet will encourage students to help one another fix their mistakes. It’s kind of messy – a lot of chaos and shouting across the room, “Hey, who got 18 wrong? How did you fix that?”, but it is worth it.

One more thing: This only works if you have comprehensive online instructions for your students. Telling them what they got wrong is only helpful when you can provide access to tools that will teach them how to get it right. We are expanding this into a more fleshed out online research guide (Soon! It’s coming soon!), but this is what we link to in comment #6.

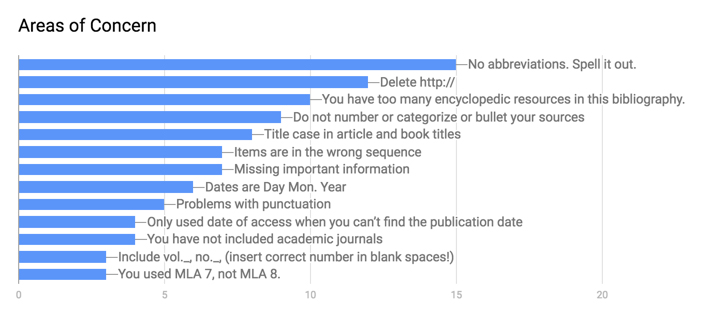

Later… I crunched the numbers and here were our areas of concern:

So I created a slide show

Which became a video lesson for the teacher to use in class (I will be out the day she wants to teach it).