As the inventor of reverso poetry and the author of numerous books of poems, Marilyn Singer is a poster child for National Poetry Month. “Usually, when April rolls around, I get to celebrate poetry by doing interviews, Skype visits with schools, and sometimes bookstore appearances,” the award-winning author and poet says.

As the inventor of reverso poetry and the author of numerous books of poems, Marilyn Singer is a poster child for National Poetry Month. “Usually, when April rolls around, I get to celebrate poetry by doing interviews, Skype visits with schools, and sometimes bookstore appearances,” the award-winning author and poet says.

Singer has been writing poetry since third grade. Often she will recite one of her first poems, “My Ocean Fright,” when making presentations. “I think that even with its problematic grammar, it gives an indication of some of my early interests in language, humor, love of animals, and imagination.” That love of language, nature, and imagination grew as the years passed, and Singer became an English teacher in order to share her appreciation of language with young people.

“My parents read poetry and sang to me, so I developed an appreciation at a young age. I loved the musicality and I loved the words.”

“I taught high school English,” shares Singer, “which involved both literature and composition. Poetry was a major part of my curriculum. I used both poems and lyrics frequently, and I always read those aloud. I think that appreciating poetry starts with hearing it.”

Though she does not believe a love of poetry can be “taught”, Singer is a strong proponent for encouraging an appreciation of poetry by modeling it. “Teachers and parents can become more comfortable with poetry by reading it themselves and finding the poems that sing to them—and that includes a lot of works written for children. Then they can read these to their students and children and encourage the kids to read or recite them back. Parents and teachers can and should be playful with poetry. On my website is a piece I wrote for School Library Journal entitled “Knock Poetry Off the Pedestal” which includes a variety of ideas for using poetry in classrooms and can also be adapted by parents.”

“Today, I’m still moved by how poems get to the heart of the matter (and often the matters of the heart). I really appreciate the specificity of language and the capturing of perception and emotion in a small space.”

These days, poetry seems to come in all forms. But what makes a good poem? For those who are learning to appreciate poetry, Singer has some counsel: “Poetry is not always easy to define. If it rhymes, it’s a poem—but it may not be a good one. And, of course, not all poems need to or do rhyme. Recent Wilder Award-winner Nikki Grimes once said about verse novels that if you read ‘page after page after page without once encountering a metaphor, a simile, assonance, consonance, internal rhyme, meter, or any other poetic element,’ it’s not poetry. That’s not saying those books are bad—just that they’re not actually verse. Not only do I agree with that, but I think it tells you something of what a poem is. It needs those elements. Again, though, the elements alone don’t create a good poem. A good poem, whether narrated by a character or by the poet her/himself, uses words wonderfully, and it uses them to capture specific moments in a fresh way, a way that makes the reader exclaim with delight, ‘Yes, that’s it! That’s right!’”

As many teachers, librarians, and parents can attest, not everyone loves poetry. In fact, there are some who think they despise it. Singer has advice for these readers as well. “To those who are convinced they ‘hate’ poetry, I say you just haven’t found the poetry you like yet. One of my good friends thought he disliked poetry until he read my book, Mirror Mirror: A Book of Reversible Verse (Dutton Children’s Books, 2010). He, his wife, and her family took turns reading it around the dinner table. He said he’d never enjoyed poems before. Heaven only knows which ones he’d encountered before, but I do think he is now more willing to look at other poetry collections with a less-jaundiced eye to discover what he does, in fact, like.”

“Poetry is a reflection of the imagination—a combination of seeing things in a new way, wondering about those things, and appreciating that wonder. It pairs beautifully with all studies. It’s fun to compare what fog is scientifically and how a poet views it, or to read a prose piece on a president and see how that person is presented in a poem, or to discover how a myth can be turned on its head or to put into words the feeling you get when you hit a home run. Poetry can make you think, and through its music, it can also aim straight for the soul.”

Singer’s first collection of poetry, Turtle in July, was published by Simon & Schuster nearly 30 years ago. However, in the early 2000s, she accidentally discovered a new form of poetry she later called reverso poetry. “One day I was watching my cat snuggled in a chair and this popped into my head:

A cat Incomplete:

without A chair

a chair: without

Incomplete. a cat.

“That little poem got me excited and I wondered if I could write more like it. So I did. The poems were on a variety of topics, but quite a few of them were based on fairy tales. I called the poems ‘reversos,’ but it was my wonderful husband, Steve Aronson, who actually came up with the word. Before that I was calling them ‘up and down poems,’ but he said we needed something better, and presto, the word ‘reverso’ was born!”

Writing reversos is not as simple as it may seem. There are strict rules to follow which qualify poems to be included in this poetry category.

1. Each reverso consists of two halves.

2. When the lines of the first half are reversed, they can have changes ONLY in punctuation and capitalization.

3. The second half must say something completely different from the first half.

“I’ve spoken with school groups and have been delighted to discover that kids of all ages have been trying to write reversos, sometimes with really fine results. Some published poets have been writing them as well. Jon Arno Lawson published several good ones in his book, The Hobo’s Crowbar (Porcupine’s Quill, 2016).”

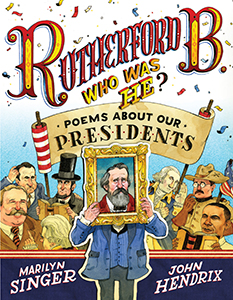

Of course, Singer also has several collections of reversos to her credit with Mirror Mirror being the first. “I don’t yet know when or if I’ll be writing more collections of reversos, but I have been slipping single poems into other poetry books of mine. For example, there’s a reverso about Richard Nixon in Rutherford B., Who Was He? (Disney-Hyperion, 2013), illustrated by John Hendrix, and there’s one in my forthcoming book of poems about New Year celebrations entitled Every Month Is a New Year, which will be published by Lee & Low this coming fall (2017) and illustrated by Susan L. Roth. I intend to keep sneaking them into other books as well.”

In addition to writing reversos, Singer continues to write poetry books, picture books, and even a novel. “Coming out next year are Have You Heard About Lady Bird? (Disney-Hyperion), poems about our First Ladies, illustrated by Nancy Carpenter; I’m the Big One Now (Wordsong/Boyds Mills), poems about seminal moments for five- and six-year-olds, illustrated by Jana Christy; and my sixth picture book about Tallulah, a young ballet student, Tallulah’s Ice Skates (Clarion), illustrated by Alexandra Boiger. Currently, I’m working on another poetry book about presidential pets for Disney-Hyperion and, heaven help me, a middle-grade novel, which is a ghost story.”

“Poetry can make you laugh, as well as cry, think, get angry or happy!”

And what is Marilyn Singer doing for National Poetry Month? “This year, to kick off the month, I’m having a party/signing to launch my latest poetry book, Feel the Beat!: Dance Poems that Zing from Salsa to Swing (Dial, 2017), illustrated by Kristi Valiant. It’s a series of poems in the rhythms of social dances and it includes a CD of me reading the poems to original music by Jonathon Roberts. There will be readings, demos, and, oh yes, dancing!”

MY OCEAN FRIGHT

By Marilyn Singer, Age 8

When I was walking on the ocean floor,

there were many sights to adore.

But one sight gave me a fright.

It was a whale with a long tail

that I simply drat,

and I went so close that with his tail

he went spat, spat, spat.

TEN TIPS FOR WRITING POETRY

By Marilyn Singer

(Source: http://marilynsinger.net/onwriting/ten-tips-for-writing-poetry/)

- Pay attention to the world around you—little things, big things, people, animals, buildings, events, etc. What do you see, hear, taste, smell, feel?

- Listen to words and sentences. What kind of music do they have? How is the music of poetry different from the music of songs?

- Read all kinds of poetry. Which poems do you like and why?

- Read what you write out loud. How does it sound? How could it sound better?

- Ask yourself: does this poem have to rhyme? Would it be good or better if it didn’t? If it should rhyme, what kind of rhyme would be best? (For example, 1st and 2nd lines rhyme; 3rd and 4th lines rhyme—“Roses are red/So is your head/Violets are blue/So is your shoe”; or 1st and 3rd lines rhyme; 2nd and 4th lines rhyme—“What is your name?/Who is your mother?/This poem is quite lame/I should try another.”

- Ask yourself: does this poem sound phoney? Don’t stick in big words or extra words just because you think a poem ought to have them.

- A title is part of a poem. It can tell you what the poem is about. It can even be another line of the poem.

- Before you write, think about what you want your whole poem to say.

- If you end up saying something else, that’s okay, too. Poet X.J. Kennedy says, “You intend to write a poem about dogs, say, and poodle is the first word you’re going to find a rhyme for. You might want to talk about police dogs, Saint Bernards, and terriers, but your need for a rhyme will lead you to noodle and strudel. The darned poem will make you forget about dogs and write about food instead.”

- Go wild. Be funny. Be serious. Be whatever you want! Use your imagination, your own way of seeing.