We here at Mackin have been thinking a lot about makerspaces, creativity, and hands-on education in schools and libraries recently, so we are especially delighted with this guest post from Aaron Becker, creator of the wordless picture book trilogy that began with Journey. For those of you implementing makerspaces into your libraries or working to foster curiosity and wonder in your students, this post will speak to you.

We here at Mackin have been thinking a lot about makerspaces, creativity, and hands-on education in schools and libraries recently, so we are especially delighted with this guest post from Aaron Becker, creator of the wordless picture book trilogy that began with Journey. For those of you implementing makerspaces into your libraries or working to foster curiosity and wonder in your students, this post will speak to you.

Like most boys of my generation, I was really, really into Star Wars. Back then, merchandising wasn’t quite what it is today, and it took George Lucas a full year to produce the toys we all desperately wanted. So by Christmas 1978, we were ready. And that’s when my Mom gave me one of the best presents I’ve ever received.

One foot wide, wooden, and hastily glued together, my mother announced “It’s the Cantina. From Star Wars.” I immediately bought it, hook, line, and sinker. The construction was flimsy and rough; there were no stickers; no catalog or instructions, but it was just what I wanted. Not only was my mom giving me a play-set for my small collection of action figures, but she was also showing me that with a few scrap pieces of wood from the lumberyard and a bit of ingenuity, you could make something. She may have not had enough money to buy all the toys I wanted, but she could meet me on my turf, in a galaxy far, far away.

Later that year, she asked a friend with some carpentry skills to build a workbench. It was a behemoth; sturdy; ready for pounding and sawing by a young boy ready to make stuff. She got me an old hammer, an old saw, a box of nails, and more scraps from the lumber yard. I went to town. I built airplanes, boats, starships; you name it. No instructions; just the raw materials and the faith from my parents that I could do it on my own. There were, of course, times when I wished I had had a bit more parental guidance; like when the pinewood derby came along at Cub Scouts and the other boys would show up with their souped-up model cars, clearly built by their more industrious, talented fathers. My mother’s approach? She brought home a set of weighted ball bearings to see if I could figure out a way of helping my car accelerate down the track. My car was clumsy, but 100% my own invention. I didn’t win anything. But in the long run, this hands-off approach by my parents has worked wonders. I was given the tools I needed and I learned how to do the rest.

I always think of this in contrast to the “art” kits one can buy for children at toy or craft stores. There’s nothing inherently terrible with such a gift – I mean, you’re giving a child a chance to be build something. But are you really? The box comes with everything you need; usually pre-cut. An instruction manual. A book of stickers. A set of pre-mixed paints. Is this creativity? For the tired parent, it’s certainly a step up from plastic toys, and most certainly better than the instant electronic babysitter: the iPad. But I would say it’s a very different gift than a piece of wood and a saw and a safe place to build.

“With this approach to making stuff, it’s no surprise then that when I ventured to write a children’s book, I chose to work in the wordless format.”

With this approach to making stuff, it’s no surprise then that when I ventured to write a children’s book, I chose to work in the wordless format. Picking up a wordless book is sort of like receiving a workbench with no instructions; just the raw tools of storytelling. The rest is up to the reader to assemble the parts. And like the scrap-wood Cantina play-set, it’s not something so easily consumed; it requires a bit of work on the reader’s part to make it come to life – to give it value by engaging with what’s been presented.

“But in my experience, it’s more about setting the stage and getting out of the way. Building the workbench, so to speak.”

If you think of your standard library reading of a children’s book, there’s always a bit of back and forth between the librarian and the children. But ultimately, it’s a situation of something given to the child for consumption. You’re reading TO a child. This is not the case with a wordless book. Here, a child is asked to actively come TOWARDS the book. It’s an engaging process that invites ownership. As the child begins to understand that it’s their job to interpret what they’re seeing, a whole world of opportunity opens up. A reader is more likely to care about the characters if they’re the one telling the story. They’re more likely to project their own emotional needs onto the protagonist’s plight. And instead of consuming a story, they’re creating one. As adults and educators, we instantly see this happening.

The parallels are strong here with effective teaching. You don’t want to have students consume information. You want them to interact with it; find something interesting on their own; make the subject something they want to pursue without your urging. A wordless book can be a great tool, for teacher and student alike, to make this all evidently clear, even with older children.

I grew up in Baltimore and went to the public schools there. I had some good classes and many bad ones. By the time I had my first art class – in sixth grade – mind you, I found the instruction narrow and limiting, so I opted out for a music class instead. My art education was self-motivated. Drawing gave me a way of understanding the world, controlling my own imagined universe that I could create on paper. It was a chance to make new worlds that I preferred over the one I found myself in. I could make the rules. I could understand what made things tick. In the end, all of the escapism served me well. I can teach myself watercolor. I can write my own stories. And now, as an adult, I can take breaks from it all and be a father, a teacher, and a husband.

I had a librarian in middle school who ran a film club. We were lent super 8 cameras and told to go out and make a film. We came back with an animated/live-action short about a playful can of soda and the destruction and confusion that ensues when the kids aren’t looking. We added sound effects, music, and voiceovers and spliced the film together. All of this with little to no training. I think it’s easy to think we have to show children everything; that without our guidance, they’ll be lost in the woods. But in my experience, it’s more about setting the stage and getting out of the way. Building the workbench, so to speak. Show an example of how curiosity pays off. In today’s standards-driven classroom, this can be tough. But the cost is huge. Without curiosity, learning becomes mechanical. And when this happens, the innate wonder of children gets lost. For many adults, we’ve simply forgotten this ever was our right: to be curious – to wonder.

So the question becomes: how do you show a child that what they’re curious about is valuable in and of itself. For by doing so, by building value in the object of their curiosity, the child can then see value in themselves – What I’m curious about is valuable and, therefore, I am valuable too, whether that curiosity is based close to home or in a galaxy far, far away.

—

From the Publisher

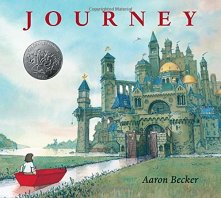

About the Author: Aaron Becker’s Journey was named a Caldecott Honor Book by the American Library Association in 2014. He has worked as an artist in the film and animation industry, where he helped define the look and feel of characters and stories and the movies they become a part of. With Journey and Quest, he has created characters and worlds of his very own using traditional materials and techniques. Aaron Becker lives in Amherst, Massachusetts, with his wife, daughter, and cat.

About the Author: Aaron Becker’s Journey was named a Caldecott Honor Book by the American Library Association in 2014. He has worked as an artist in the film and animation industry, where he helped define the look and feel of characters and stories and the movies they become a part of. With Journey and Quest, he has created characters and worlds of his very own using traditional materials and techniques. Aaron Becker lives in Amherst, Massachusetts, with his wife, daughter, and cat.

About Journey: A lonely girl draws a magic door on her bedroom wall and through it escapes into a world where wonder, adventure, and danger abound. Red marker in hand, she creates a boat, a balloon, and a flying carpet that carry her on a spectacular journey toward an uncertain destiny. When she is captured by a sinister emperor, only an act of tremendous courage and kindness can set her free. Can it also lead her home and to her heart’s desire? With supple line, luminous color, and nimble flights of fancy, author-illustrator Aaron Becker launches an ordinary child on an extraordinary journey toward her greatest and most exciting adventure of all.