As a child, award-winning author Markus Zusak knew what he wanted to be when he grew up: a rugby player and a house painter. “As a kid I was obsessed with a type of rugby, and I thought I could do that and be a house painter like my dad. That said, I was never quite good enough, strong enough, or fast enough! I also realized there was so much pain involved.”

The fourth child in his German Austrian family, Australian-born Zusak wasn’t especially studious, but he was a determined young person. “I was essentially focused on what I loved—it was all or nothing—so I did well in English and terrible in things like woodwork. I remember everyone making these nice spice racks and mine was two pieces of wood with a nail in it. It was the same with English in some ways: I dutifully read books I didn’t like as much, but the ones I loved I would read outside of school as well, over and over.”

It wasn’t until he was a teenager that Zusak resolved to embark on a writing career. “When I was 16, I decided I wanted to be a writer and that nothing would stop me,” shares Zusak. “I attribute a lot to S.E. Hinton, who showed us that kids could write books by writing The Outsiders (Viking Press, 1967) at 16. Then, when I read Taming the Star Runner (Dell, 1988) at that exact age, in which the protagonist gets a book published, I decided I’d give it a try myself—and those eight pages could be entered into a competition for the worst book ever written.”

“There’s likely as much pain in writing a book as there is when a 100-kilo oaf lands on you, but I’d always been slightly different from my rugby-playing friends and foes. Not only was I one of the few immigrant kids who played in the area I grew up in, but I loved books. I loved English. When I read books, I would want to look like the characters, talk like them, become them.”

However, Zusak never lost sight of his goal to be a writer. He went on to be a substitute teacher, but continued to write on the side until he could dedicate himself to his passion full-time. Since then, he has published five novels, with one, especially, finding unexpected success.

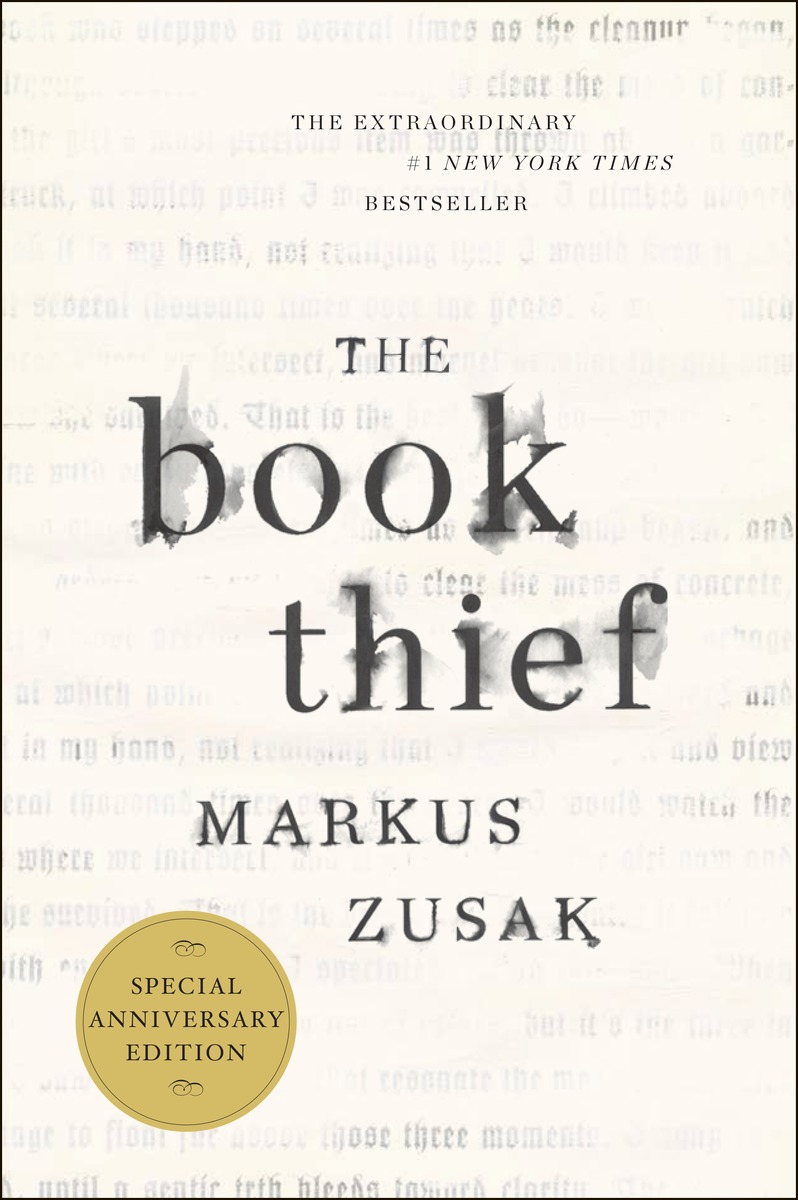

Ten years ago, Zusak’s young adult novel The Book Thief (Knopf Books for Young Readers) took the literary world by storm. First published in 2006, it spent the equivalent of more than seven years on the New York Times Best Seller list. It received award upon award and was finally made into a movie that was released in 2013. This year, Knopf released a 10th-anniversary edition of The Book Thief, and Zusak embarked on a promotional tour in the United States.

“I didn’t ever think The Book Thief would be successful at all,” confesses Zusak. “Actually, I thought it would be my least successful book. In that sense, I decided that I would follow its vision completely. I figured since no one was going to read it anyway, I might as well do it exactly how I wanted; I felt like I had nothing to lose. It was supposed to be a small book, but that changed as soon as Death came in as narrator. From there, it just kept growing, and I didn’t ever really attempt to rein it in. I also loved the toil of it, and it meant everything to me. Maybe that’s what people pick up on—but such books can also go unrewarded. It’s always been a lucky book.”

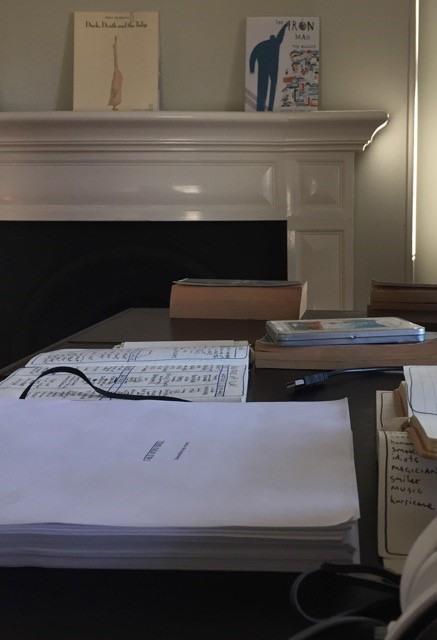

Though he believes The Book Thief is a lucky book, he does not believe success comes by luck. A disciplined writer, Zusak is diligent about dedicating time to write and following established methods. “I’m a real believer in rituals, yet I often find myself trying to reestablish routine. Sometimes you can spend too much time clearing everything else out of the way and you never get to the real work of writing. I like to be at my desk around the same time every day, which is usually a little before the actual start time. I try to work for five hours as a base and see what happens after that. The idea is to get to my desk feeling strong rather than tired. Then I try to labor to the point where it doesn’t feel like work anymore.

“I always wanted to write novels. Even when I tried to write other forms for training purposes, I found I wasn’t really trying. Again, it was all or nothing.”

“Sometimes I also go away to work, just to be totally alone for a few days, although I do take our two dogs with me. They generally sit with me in my office anyway and give me dirty looks when I’m not working. Or remind me it’s time to go out.”

In addition to touring for The Book Thief, maintaining a blog and social media accounts, and balancing family life, Zusak has also been working on his next book, Bridge of Clay, about Clay Dunbar, who leaves his four brothers to build a bridge with their father.

“In the end, I consider myself lucky that I realized what I wanted to do quite early. Even on bad writing days, there’s nothing else I’d rather be.”

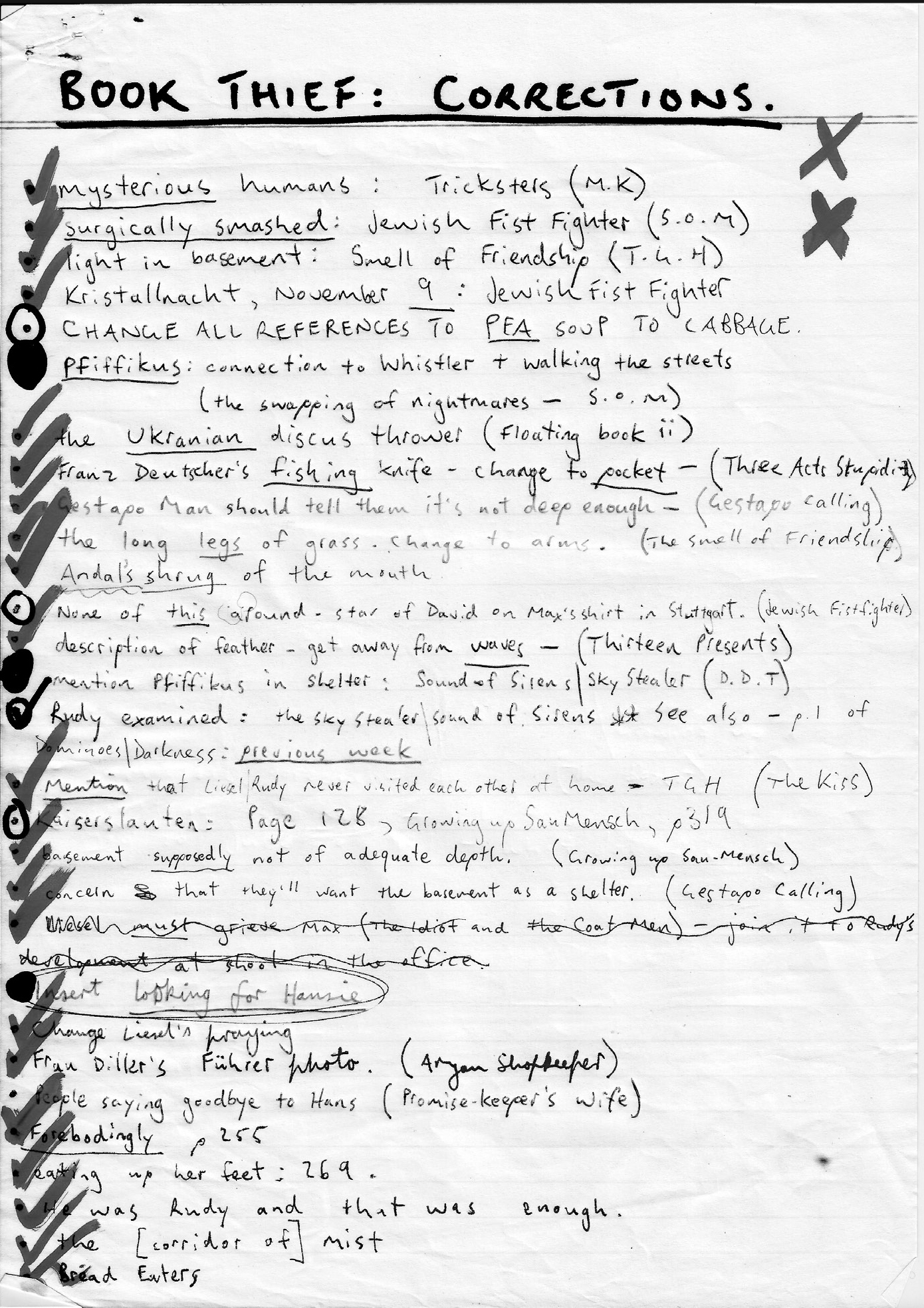

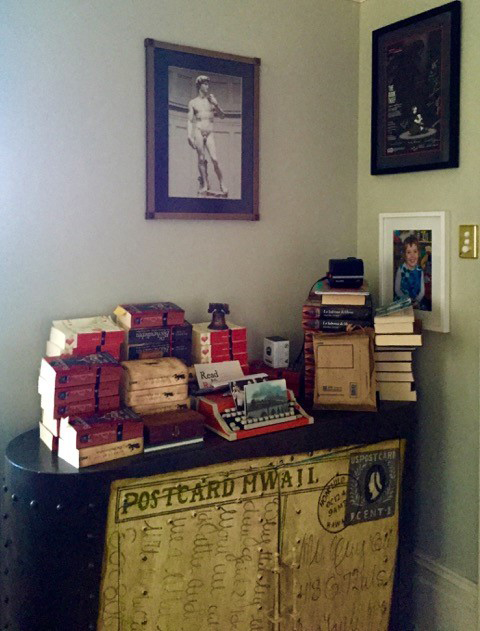

Manuscript of The Book Thief

On Tour With The Book Thief

“The first tour was special because I’d never had that sort of success, and this one was special because the book wasn’t so fresh in my mind anymore. It’s been through its ups and downs and come out the other side.

“This time around it was especially great to meet so many readers, and also come to the realization that in every city there were people ranging from 10 years old up to people in their 80s. When you see a range like that it gives you faith that people are definitely still reading, and that books are still meaningful to people of all ages. Also, seeing kids with their parents, where the mum or dad says ‘My daughter (or son) introduced me to this book’ is always a highlight.”

How to Raise Good Readers and Writers

“I’m finding more and more as a parent that I just try to read more visibly myself, so that my kids see me reading. There’s no point telling them they should read more when you could actually be saying, ‘Hey, listen to this bit—’ We never make reading a chore. It’s always nice when kids walk around quoting the book they’ve been reading. A real favorite lately has been my son quoting Hagrid telling Dudley Dursley, ‘Budge up, yeh great lump!’

“My parents could have poured a whole lot of time and effort into helping me at school, or giving me greater encouragement, but they pretty much left me alone, and that was a good thing, I think.

“It was very important to them that we had a lot of books in our house. We had hundreds of Dr. Seuss books, hundreds of other books. We had an environment rather than a schedule; we were expected to do well, but not forced. In my case, I had my own standards too, and I’m grateful to my parents for the fact that I was left to find my own interests, and obsessions. The greatest gift they gave us was telling their stories.

“I went to a very standard public school. I always had good English teachers, but even then I was never noted as a particularly creative student. My best marks were always for essays; whenever there was a creative task it didn’t go as well as I’d hoped, but I always believed that was what I was going to do.

“Even now, I tell kids not to be too concerned with their results or winning writing competitions. Kids who win writing competitions tend to win everything—they just have that knack; they’re just good at winning things, and it’s all the toil and sustained groundwork that gets books written, not flashes of brilliance.”