Congressman John Lewis is a legislator who has earned the respect of colleagues from both sides of the aisle. Lewis grew up as the son of a sharecropper, but he had no intention of following in his father’s footsteps. Lewis craved knowledge, pursued education, and dreamed of being a preacher. But as a young adult, his life direction was forever changed when he became a torchbearer for the civil rights movement in America.

Over the years, Lewis experienced severe brutality; yet, he remained a strong advocate for civil rights through nonviolent protests. He refused to be defeated or to give up the idea of equal treatment for all. Since 1987, Lewis has served as a U.S. congressman.

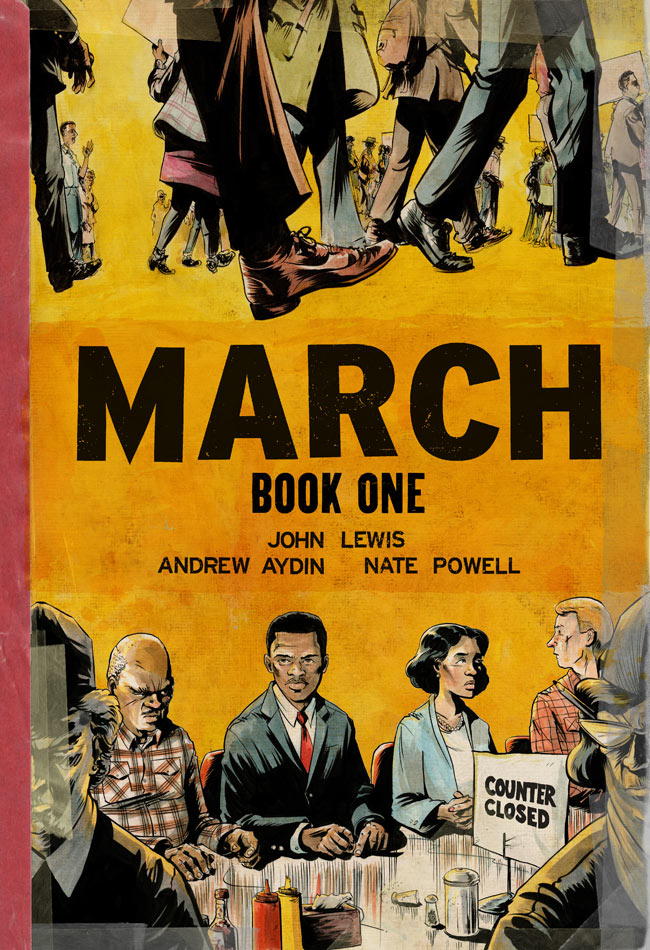

In 2013, Lewis, along with staffer Andrew Aydin and cartoonist Nate Powell, worked to bring Lewis’ story to life through a graphic novel trilogy entitled March (Top Shelf Productions).

Last year the first of your three graphic novels was introduced. The reaction and reception has been stellar. Communities and schools have adopted March: Book One as essential reading. Further, it has received several notable honors including being named as a best book on numerous lists and being designated as a New York Times and a Washington Post bestseller. Did you ever expect this level of success?

John Lewis (JL): I never dreamed, or thought that this book would receive as much attention as it has, but I’m very, very pleased that thousands of young people—and people not so young—are reading March. And not just reading, but being inspired to live a nonviolent way of life.

Andrew Aydin (AA): When this project was just an idea, we saw that it had potential and it was an absolutely necessary contribution to the national conversation. That doesn’t always translate into public recognition, but in this case it did. I think a lot of that has to do with how hard we worked to make the March series authentic in the way in which John Lewis’ story is told. But more than anything, it speaks to how much of a contribution John Lewis has made to this country, and how thirsty young people are today to learn from real heroes who were young and frustrated and who were not afraid to risk their very lives to achieve meaningful progress. This generation is different. They are not as interested in chasing money or material possessions. I believe that this generation is more interested in seeking social change and a more just society than any generation since those that brought about the civil rights movement and the struggles for human dignity of the 1960s.

Nate Powell (NP): I was aware that this project would have a higher level of visibility than any other book I’ve done thus far, but none of us had any idea exactly the potential scope or scale until the month that Book One rolled out. We’ve worked hard to adapt to the changing and expanding role of the book itself in real time, concurrent with our work creating Book Two and Book Three (and keeping the work itself at the forefront of our priorities). Much of the reason we weren’t quite able to gauge the project’s impact was precisely because of the personal, powerful responses from readership, libraries, and schools—that’s really where the book must speak for itself to carry its own weight.

Nate Powell (NP): I was aware that this project would have a higher level of visibility than any other book I’ve done thus far, but none of us had any idea exactly the potential scope or scale until the month that Book One rolled out. We’ve worked hard to adapt to the changing and expanding role of the book itself in real time, concurrent with our work creating Book Two and Book Three (and keeping the work itself at the forefront of our priorities). Much of the reason we weren’t quite able to gauge the project’s impact was precisely because of the personal, powerful responses from readership, libraries, and schools—that’s really where the book must speak for itself to carry its own weight.

Why did you choose the graphic novel format for such an important story?

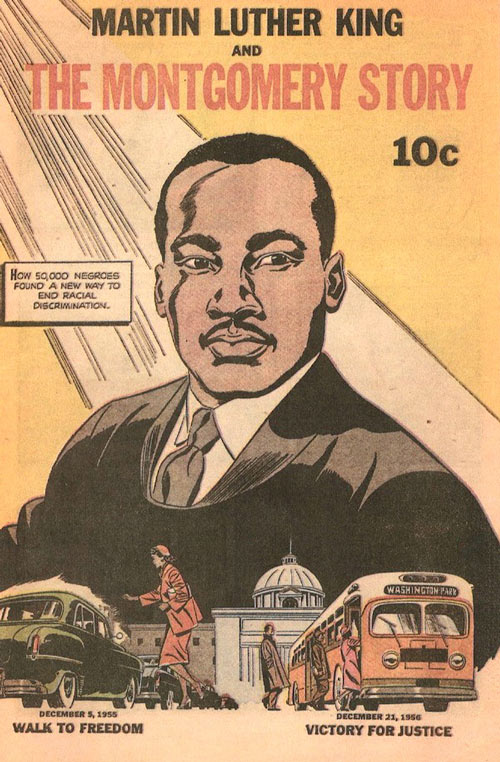

JL: Well, I never will forget that when I was very young, during the ‘50s, I came in contact with Martin Luther King and the Montgomery Story, a book of 14 pages that sold for 10 cents, which had a major impact on my life. And one of my staffers, who is the co-writer of March, came to me and suggested that I should write a comic book. He was very enthused about it — he had been a voracious reader of comic books since he was a very young child. And I finally said to him, “Let’s do it … but I will only do it if you do it with me.”

AA: I have been a comic book fan nearly all my life. My fascination began as a refuge after my father left because it was within the stories told in comics that I could find heroes who fought for justice and where outcasts or misfits could find purpose and commonality. But over time I have come to love comics as a medium for its ability to tell stories with tremendous depth and emotion that in some ways go beyond what is possible solely with the written word.

Growing up in Atlanta, I was often exposed to the stories of the civil rights movement. After working for Congressman Lewis for a few years, during which time I often heard him tell these amazing firsthand accounts of his life in the struggle to young people who would hang on his every word, my eyes were opened to how necessary and important it was to find a new way to make his story accessible and available to everyone, those who are young and those not so young. Call it fate or the Spirit of history, but when Congressman Lewis told me about the 1957 comic book Martin Luther King & The Montgomery Story and how it had helped inspire young people to join the civil rights movement, it felt like I had a mission to convince him to write his own comic book.

Growing up in Atlanta, I was often exposed to the stories of the civil rights movement. After working for Congressman Lewis for a few years, during which time I often heard him tell these amazing firsthand accounts of his life in the struggle to young people who would hang on his every word, my eyes were opened to how necessary and important it was to find a new way to make his story accessible and available to everyone, those who are young and those not so young. Call it fate or the Spirit of history, but when Congressman Lewis told me about the 1957 comic book Martin Luther King & The Montgomery Story and how it had helped inspire young people to join the civil rights movement, it felt like I had a mission to convince him to write his own comic book.

Why did you choose to create a trilogy instead of just one book?

AA: The first draft of the script for March that was completed in 2011 called for 284 illustrated pages and was 315 pages in length. It was very dense because we were trying to fit in as much information as possible while keeping the length manageable for a single volume. After Nate took a look at it, he told us there was no way to fit everything into that length, that we had to draw it out and let the pages have space for the visuals to tell the full story. That was an important turning point, because then we started looking at a 500-600 page story which would take years to draw. So we agreed to split it up and tell the story in pieces. Essentially we broke it up into the three acts so that Book One is act one, and so on. This turned out to be much better for all of us, because it allowed me and the congressman to go back and tell more of the story, adding anecdotes and facts that might otherwise have been cut, and it also allowed Nate the space to dive into the visuals and draw out those moments of tension and emotion that would have been shortchanged, so we can fully utilize the strengths of the comics medium.

The first book carries us from Congressman Lewis’ childhood through to the gathering on the steps of city hall. What can readers look forward to in Book Two and Book Three?

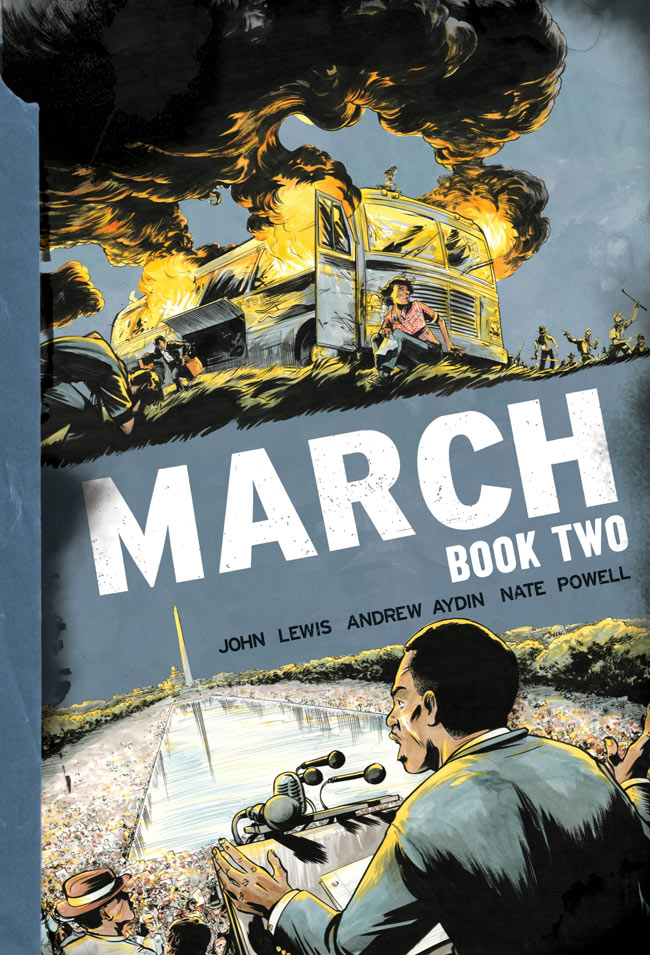

JL: In Book Two and Book Three, readers should be prepared for an unbelievable ride. Book One set the stage, but I tell you, Book Two and Book Three will make it plain, and crystal clear, what I lived through, what I witnessed: through the Freedom Rides, the March on Washington, the March from Selma to Montgomery … if it hadn’t been for some of these pivotal moments in my life, I wouldn’t be the person that I am today.

AA: We sometimes joke that if Book One is Star Wars, then Book Two is The Empire Strikes Back. The heroes are more powerful, but the risks are also much greater. After the Nashville students learn the principles of nonviolence and use them to bring down one target, Book Two shows the development of a national student movement and how they brought themselves to the forefront of the broader civil rights movement. Among other milestones, we get a firsthand look at the 1961 Freedom Rides and go behind the scenes of the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom.

How did the collaboration between the three of you work?

NP: Andrew and the congressman spent a few years working up the basic script before I came on board; for each volume, the story now manifests itself nearly in real time. We all (including our editor Leigh) spend time every day doing research and reference, digging up questions to the established historical record at times, as I pencil the book and send it back to everyone for notes. Congressman Lewis, Andrew, and I spend a lot of time on the road doing presentations, too, and during those trips we sometimes are able to take time to sit together and discuss the book in progress. The script and artwork change and are refined constantly, from the pencil stage through several intense weeks of 20-hour editing days, leading right up to the deadline. It’s a very hands-on experience for everyone involved.

JL: The collaboration worked very well. Book One, Book Two, and Book Three will continue, I think, to emerge as pieces of classic literature, not just on the civil rights movement, but on the philosophy and discipline of nonviolence.

The country has come a long way since segregation was commonplace. Why do you feel it is important to bring the ugliness back to life? March definitely does not smooth over the nastiness; rather, it portrays the horrors of that time: beatings, killings, and the “N” word. Why is the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s relevant enough to produce books for today’s young people?

JL: Well, I think it is important. I think it is a must for young people and generations yet to come, to understand, to feel, to touch, to almost smell the drama of what happened a few short years ago. So maybe, just maybe, we will never ever repeat this unbelievable time in our history. We have to tell it all, and make it plain, and make it clear, so people will never ever forget the distance we have come, and the progress we have yet to make.

I hope March will inspire another generation of people, and not just children and young people, but all Americans, and people from around the world, to be committed to a life of service, committed to a way of peace and nonviolence, to help leave our little planet a little more peaceful and a little more human. March will say to humanity that we are one people, we are one family, we all live in one house: the world house.

NP: If it’s not the whole story, it isn’t the story at all. There are plenty of whitewashed recollections of the movement or of the Jim Crow South in general. Also at the forefront of our minds is our increasingly short collective cultural memory.

I was born in the late ‘70s and grew up in the deep South, and I was very much still of an era where racism was a casual part of white people’s public and private lives, though it had been pushed more into its own little echo chamber by then. As a five year old, I saw a fully costumed Klan circle, complete with burning cross, on a town square in rural Alabama at high noon.

A decade passed between King’s assassination and my birth, but the older I get, the more acutely aware I become that 10 years is nothing. Still, I spent most of my adult life before March with the assumption that most young people grew up with a general, working knowledge of the civil rights struggle and its figures. I was very wrong.

The struggle has never ceased, and has only become more and more important, but I now understand that losing these immediate, first-person accounts of our collective history is one of the major factors allowing for the inequality, oppression, and brutality we continue to see throughout our society. So we make it real, make it plain, make it something that shows the dedication and impact of young people who were much like any of us.

A center point in the civil rights movement, according to March, is nonviolent actions. Recent events, however, demonstrate that perceived discriminatory issues are still alive and well and the associated protests are far beyond peaceful. What is your advice to today’s protesters, especially young people? Rather than inciting violence, what are productive and peaceful ways for students to take a stand in our current society and to make changes in our country?

JL: Young protesters, or all protesters today, must learn from March. They must learn from what we did during the ‘60s. We didn’t strike back. We didn’t throw rocks. We didn’t hate. We accepted nonviolence as a way of life, as a way of living. Because if you want to create what we called the Beloved Community, a community at peace with itself, if that is the end, then the way we protest, our means, must be one of peace and one of love.

March is saying that we are not out to destroy property, or harm people—we are out to redeem people, to redeem our society, and create an American community, a world community, at peace with itself. March is saying to the generation of young people, and especially those protesting today, that nonviolence is one of those immutable principles that we cannot and must not deviate from.

NP: Violence from protesters themselves is extremely rare, but has been made into a talking point by those who stand to benefit from breaking the perceived legitimacy of organized protest and resistance. Organized, disciplined nonviolent resistance is alive and well, and we see it all around us in cities across the country. The rules have changed as information and technology evolve, but it’s essential that people stay in the streets, stay visible in their communities, on the news, on the Internet, and in this crucial public discussion. There are a million people just like you (or me), sharing the same doubts, fears, and insecurities that keep us from speaking out. Finding each other in our neighborhoods, online, in the streets—this is what keeps us from believing we’re alone, from giving in to hopelessness.

As a pillar of the civil rights movement in America, Congressman, what is your perspective on how far we’ve come as a nation in regard to rights and racism? If you were to be involved in civil actions and protesting, what would be your issues of concern today?

JL: Today, we have come a distance. We have made a lot of progress. That cannot be denied. You cannot dispute the fact that our country is so different from 50 years ago. But we still have problems. There are too many people that have been left out and left behind, and they are African American, they are White, Latino, Asian American, and Native American.

We have so many issues today that we need to confront. Comprehensive immigration reform. We have to solve the issue of poverty, the issue of hunger, the issue of war—spending billions of dollars to kill rather than to build. We have to deal with the fact that all of our children should be receiving the best possible education. There are hundreds and thousands of young Americans who cannot or will not receive an education, because in order to get an education, you have to spend money. Students come out of college and universities with unbelievable debt. It’s not right, it’s not fair, and it’s not just, in a society such as ours. And those dollars are not going to the teachers.

As the last member of the “Big Six Leadership” in the civil rights movement, do you feel a responsibility to pass on the torch or do you already see new faces taking over?

JL: I see every day the need to pass on the torch. But I think young people, those who will pick up the torch, in a sense must be prepared to just grab it and go for it. That’s what we did. We were able to find a way to get in the way, as I often say. To get in trouble — good trouble, necessary trouble. I think each day I spend time mentoring young people. I see hundreds and thousands of high school students, elementary school students, college students, and I travel a great deal across America, telling the story of March, as we told it in Book One and in Book Two. I think that’s my calling, my mission. I think it is part of my obligation to go out and spread the good news, and tell people: they, too, can do something. I have people call me from time to time—some of them not very young, not much younger than I am!—saying “I’d like for you to be my mentor.” And I’ve often said “Just read the books, learn the lessons of the movement, and you’ll be all right.”

“I believe that teachers—whether in elementary schools, at the secondary level, or at colleges and universities—every teacher deserves the Nobel Peace Prize just for maintaining order in our schools!” – Congressman John Lewis

What can readers look forward to seeing from you in the near future? What are your plans?

JL: Oh we have plans to continue to write, to travel, to see America, but also to see the world. The lessons of nonviolence are universal. Not just for America. There was a little brown man in India—Gandhi—who carried that message to South Africa, and then came back to India, and helped to liberate India from the British. And it was individuals like Mordecai Johnson, president of Howard University, who traveled to India, met Gandhi, came back, and started speaking here and there. Then Dr. King heard Johnson, Howard Thurman, and others, speaking about Gandhi, when he was a student at Crozer Theological Seminary in Pennsylvania. He was greatly influenced and inspired by what he learned.

NP: I’m currently doing some animated illustrations for a documentary about the Voting Rights Act that’s being produced by Southern Poverty Law Center and their Teaching Tolerance publication; it’s slated to hit 50,000 schools and a million students next year. In the fall of 2015 from Top Shelf, I’ll be releasing You Don’t Say, a collection of a decade’s worth of shorter, out-of-print stories. Once the March saga is complete, I’m also slated to draw an as-of-yet unannounced 10-issue series with writer Van Jensen for Dark Horse, and will finally get back to work on my next graphic novel, which is called Cover, and should be released in 2018 from Top Shelf.

Do you respond to fan mail? If so, what is the best way for readers to contact you?

AA: Absolutely. The best way to reach me is through my website: andrewaydin.com/contact

NP: I respond whenever I can via email (seemybrotherdance@yahoo.com), or at my site (www.seemybrotherdance.org).

JL: You can always write to me through my office in Washington. I love to hear from teachers, librarians, and young people, especially when they are reading March together and discussing it. Sometimes a school or a university will have their whole class read the book, hundreds and thousands of students at a time, and then invite us to come talk about it with them. I believe it is my obligation to tell the story of the civil rights movement to the next generation.