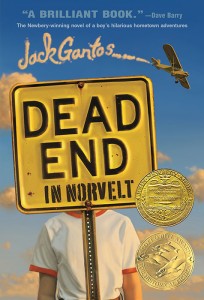

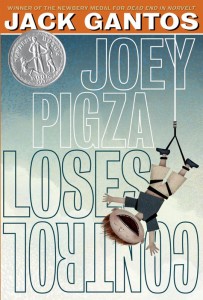

Jack Gantos is a prolific author who has written for all age groups. His work has received numerous awards including the prestigious Newbery Medal for Dead End in Norvelt (Farrar, Straus, & Giroux, 2011) and the Newbery Honor for Joey Pigza Loses Control (Farrar, Straus, & Giroux, 2000). Gantos knew he wanted to be a writer from a young age, but he didn’t enter the publishing world until after spending time in federal prison for drug smuggling. Known for pulling scenes and themes from his diaries and writing books in longhand before typing them out, Gantos is deeply invested in his work. Here, Gantos shares with Mackin’s Amy Meythaler his experiences and insights with a refreshing mix of honesty and humor.

Good Reading Comes Before Good Writing

I’m assuming “Jack” is a nickname. What is your birth name and why did you choose to write as Jack Gantos?

My father was John Gantos and he was always called “Jack.” I’m John Gantos Jr. and so I too grew up being called “Jackie” and later on, “Jack.” Naturally I used my name when I began to write and publish books.

Did an interest in reading or in writing come first for you?

Reading came first. The Brave Cowboy (Andrews McMeel, 1959) is the first book I recall reading on my own and I read it repeatedly. We also had Dick and Jane readers which I enjoyed.

Writing only came to me once my sister introduced the practice to the household. I wasn’t very good at first because I was writing as if my mother was going to read it. Once I became more honest to myself and wrote about everything weird I observed or overheard then I enjoyed it more.

When you were young, you were placed in the Bluebird group for slow readers. In your opinion, is it best to group young readers by ability or is it better for kids to be in groups of differently leveled readers?

I am still a slow reader, but to my advantage, I am a thorough reader. When I finish a book there is nothing left on the bone. It is very satisfying to see and feel every nuance of each book I read.

As for young readers and what groups they should be slotted into based on skills—every few years there is a new theory for how to niche group young students. When it comes to reading, I think there is nothing like giving a really good book to an eager reader. Who can say what group of reading kids, slow or fast, owns Where the Wild Things Are (HarperCollins, 1963)?

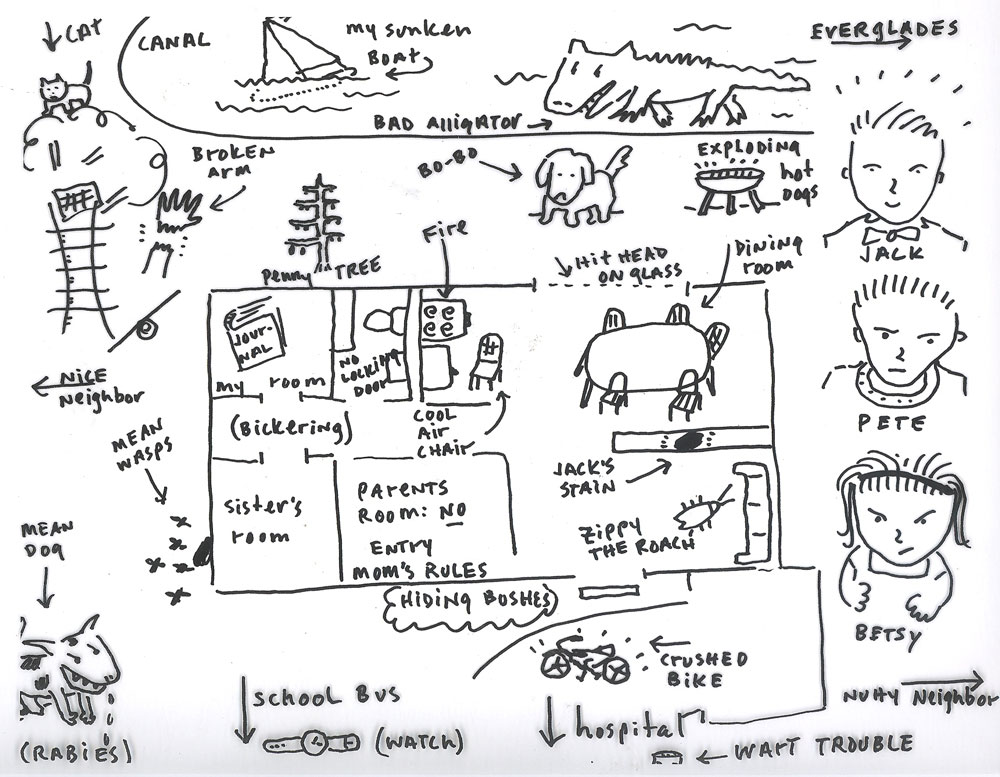

“Read or Rot” bookplate sketch

Sheaffer’s box for “Writing Fluid” (supposed to replace ink)

You became a voracious reader in your middle-grade years. Was there a certain book or a certain teacher or librarian that inspired you to read? What genre or topic captures your interest as an adult?

I can’t say that I read for any other reason than I enjoyed how the story came alive in my imagination. I think that must be why most people love to read.

I was a library rat in school and hung out in the library and read books and shelved books and helped the librarians because they were always nice to me.

As an adult I have a wide range of reading. This week I read a history of Florida, the new edition of A Clockwork Orange (Palgrave Macmillan, 1962), some Spalding Gray, and The Disappearance of Odile (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 1972) by Georges Simenon.

What are your top five or ten must-reads?

- A Cricket in Times Square (Farrar Straus Giroux, 1960)

- Harriet the Spy (HarperCollins, 1964)

- The Squirrel Hotel (Viking, 1952)

- Charlie and the Chocolate Factory (Alfred A. Knopf, 1964)

- From the Mixed-Up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler (Atheneum Books for Young Readers, 1967)

- The Borrowers (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 1952)

- The Giver (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 1993)

- Ginger Pye (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 1951)

- Half Magic (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 1976)

- Everything on a Waffle (Square Fish, 2001)

- and so many more.

Drawing from Life and Learning by Experience

It seems your writing career is rooted in the diaries you began keeping as a second grader, and your aspirations to be a writer came after reading your sister’s diary. Do you still keep diaries? Do you recommend others keep them even if there is a chance of others sneaking peeks?

Yes, I still keep diaries and writing journals as they are essential tools for me. Yes, I recommend that everyone should keep a diary and shame on the person who sneaks a peek. We all know that diaries are personal and that we should honor that code of decency. As for how to keep a journal—every approach that results in capturing thoughts on paper is a good approach. But if I had to offer a few tips I would say: Write in a journal for fifteen minutes each day and be searingly honest. If you read Harriet the Spy she really spells out the best approach to keeping a journal.

My Fifth Grade Journal and Students

© Jack Gantos. “From my 5th grade journal”

I read that your initial diaries were full of collections and notes about your “treasures”—like scrapbooks. What kind of things do you find interesting today and what do you write about?

When I was a kid I never heard of the term “scrapbooking.” I kept stamps and photos and sports tickets and movie tickets and “stuff” in my journal. Each item would remind me of an event. What I write about now is everything.

Are you a disciplined, consistent writer or more of an as-the-spirit-moves writer? On average, how long does it take you to create a book from start to finish?

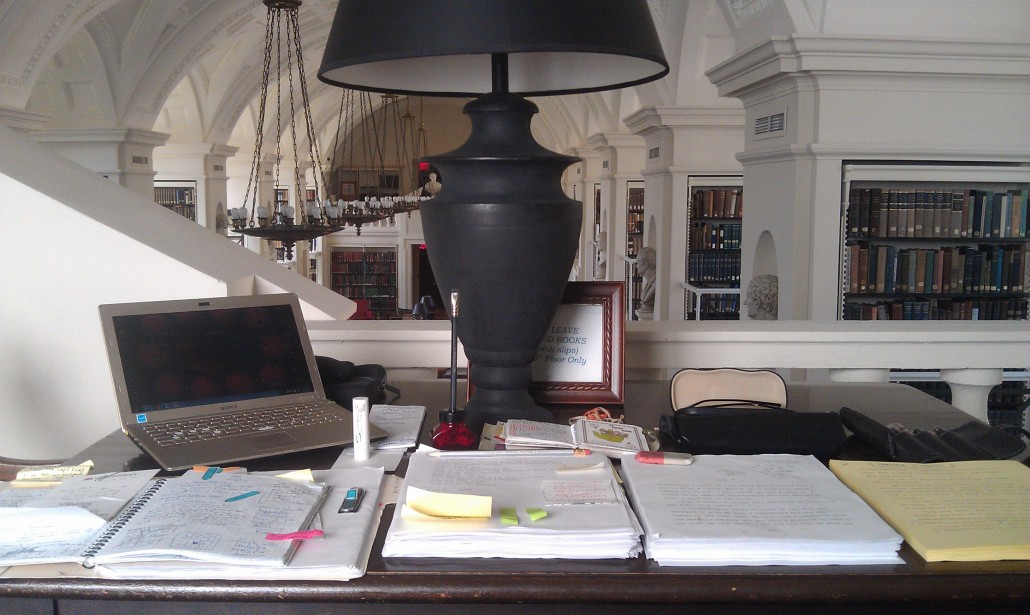

I keep to a schedule. I write in the Boston Athenaeum each day when I’m in Boston. On the road I have to write in airplanes, or trains, or hotels or wherever—restaurants are very productive spaces for writing.

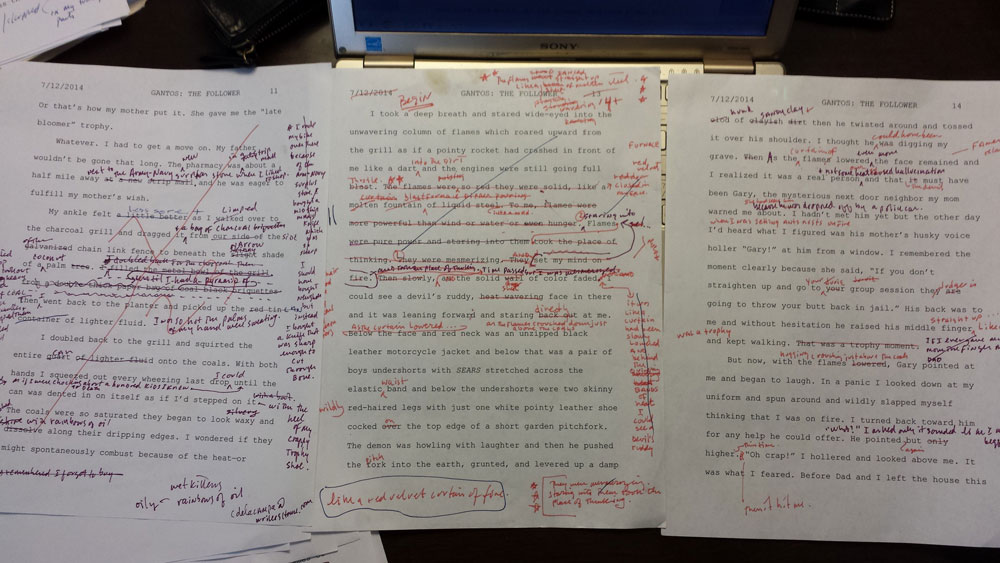

Generally I figure I can write a novel per year. I consider a hundred drafts to be sufficient.

Boston Athenaeum: From Norvelt to Nowhere working pages

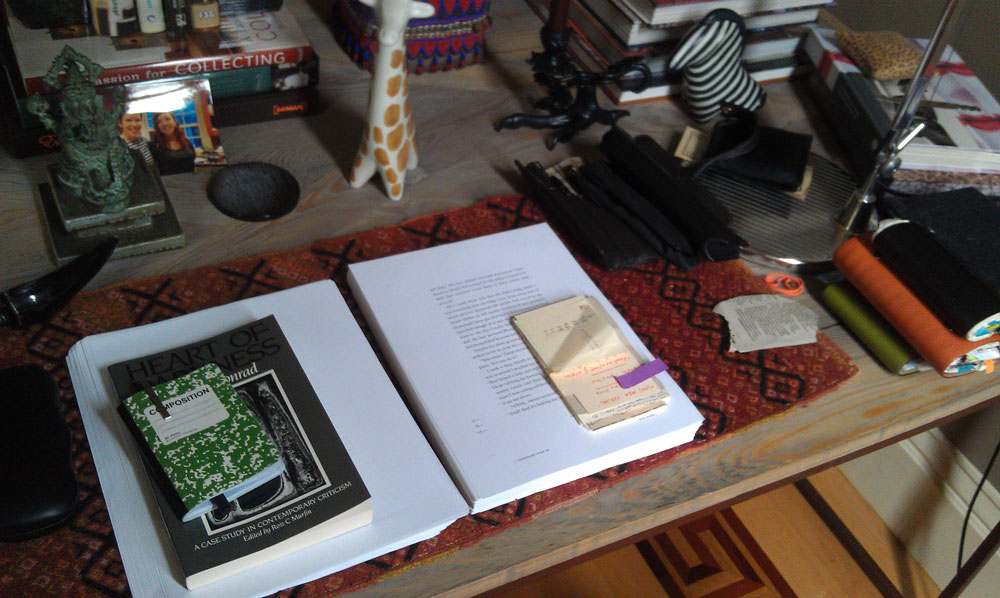

Home Desk: pages from The Key That Swallowed Joey Pigza

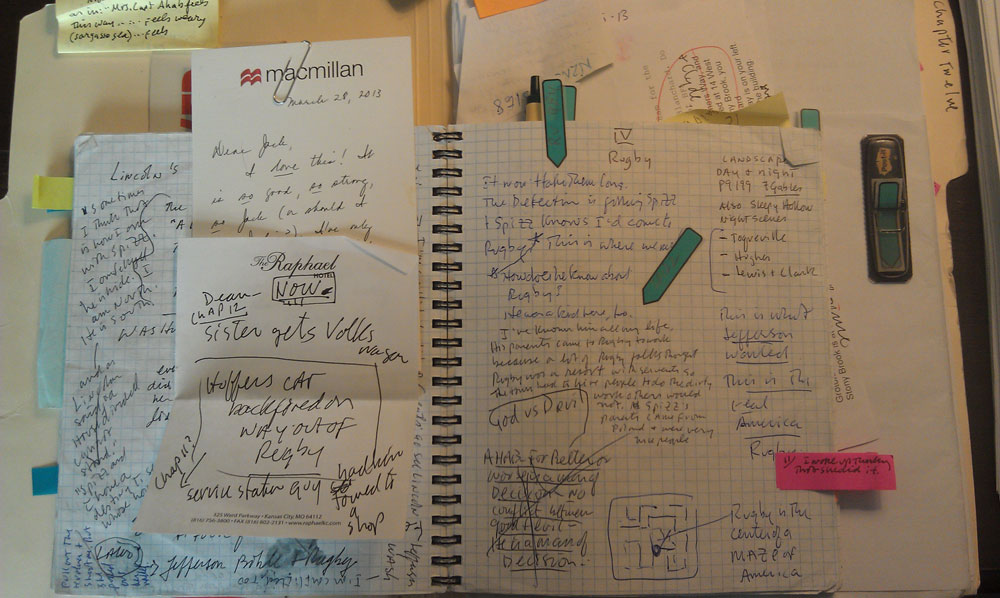

From Norvelt to Nowhere leftover bits

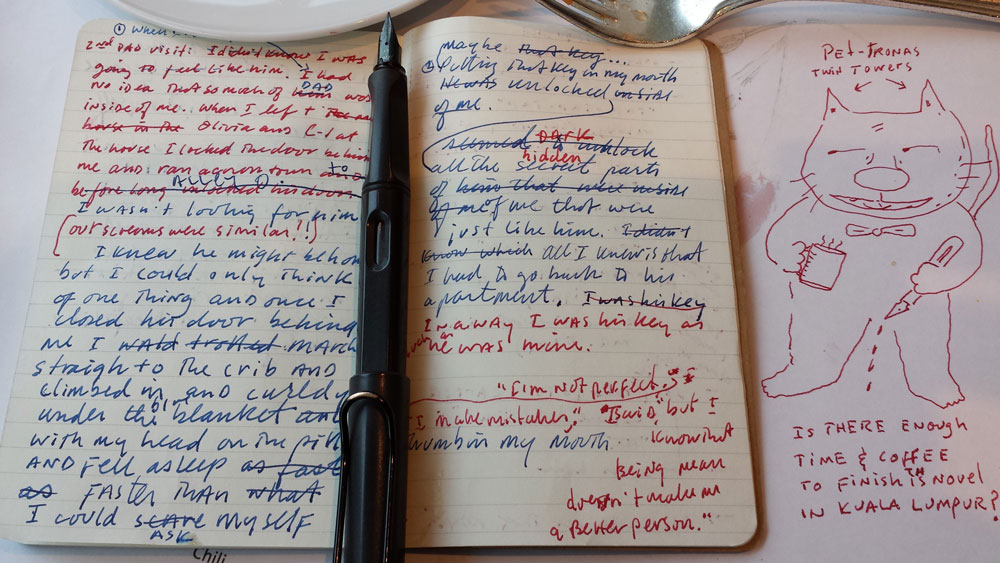

Joey Pigza notebook and Ralph drawing from Kuala Lumpur speaking tour

What was your first foray into publishing like with Rotten Ralph? Were you successful from the get go or did you have to deal with rejection?

Nicole Rubel and I met at a costume party in Boston. She was an art student at the Museum School of Fine Arts and I was at Emerson College in the writing program. We both shared an interest in Children’s Literature and so we began to collaborate. We worked very hard. We wrote and illustrated twelve failed books before we created and sold our thirteenth book, Rotten Ralph (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 1976).

We called up the publishers in Boston and set up appointments with the Children’s Book Editors and then walked in with our books which we hoped to publish. The rejections were very personal, but also very informative as the editors would point out the flaws and actually give us very good advice. All those failed books amounted to a tutorial in how to publish good books.

Over the years you have been recognized as an exceptional author. In fact, you were awarded the Newbery Medal just a couple years back for Dead End in Norvelt. Where were you and what was your reaction to finding out about that honor? What other awards are highly significant to you and why?

I was in the kitchen, feeding my cat, and preparing to leave the house and go to the library when the Newbery committee called and informed me that I had received the Newbery Award. That was quite exciting. I did not go to the library that day.

Any time I receive an award it is an honor. It means that someone or some committee has read my book and enjoyed it and judged it to be worthy of praise. I can’t ask for more. I have received many awards and each one has a place of honor within me.

Do you respond to fan mail—both online and traditional letters?

I do a bit of everything, but I’m generally a busy person and although I do a great deal of public speaking I’m actually a very private person. So I do respond to those who contact me when I can, and when I’m inspired to do so. I’m not as ubiquitous as some author/personalities, nor am I as reclusive as J.D. Salinger. I’m somewhere in-between.

Finding and Following the Write Path

Prisons seem to have played such an interesting role in your formation as a writer. First, you were a student in an old prison and then you found yourself incarcerated for drug trafficking. Do you have regrets about the decisions made as a young person or do you view them simply as learning experiences? Was it essential for you to be imprisoned to really buckle down and focus on writing?

Of course I have regrets but I’m not weighed down by them and paralyzed by guilt and shame and fear and all the ugly moments. Yes, every experience is a learning experience—from your first sleep over to summer camp to travel abroad to many other solo moments. Prison did not make me buckle down. My desire to achieve something of value as a writer made me buckle down. I wasn’t punished into achievement. If punishment was such a positive motivation then every kid who is spanked by their parents would turn into captains of industry or become the president.

Do you believe your journey to authorship would have been different if you followed a traditional path toward a writing career?

After I was paroled from the medium security prison in Ashland, Kentucky, I moved to Boston to attend college. I had always intended to go to college but I had taken a slow route. However, once I landed in Boston I went to Emerson College for Creative Writing and by my sophomore year had, along with Nicole Rubel, created and sold the first Rotten Ralph book. It was an unconventional path to college, but there was nothing unconventional about putting in all the hard work to write a book, refine it, and place it with a major publisher. All of that was pure effort—and well worth it.

As for a “traditional” path to authorship—I think every author has a pretty distinct story to tell. I can’t begin to suggest what is traditional in a field built on creativity.

Were instruction and formal guidance essential to developing as a children’s author?

I was always interested in writing. I never took a course in Children’s Literature or Children’s Book Writing. I went to the library and read a few hundred books that I loved and then spent a few hundred hours trying to write well.

You not only became a successful writer but also a writing instructor. Further, you developed master’s degree programs in children’s book writing at Emerson College and at Vermont College. What qualities and characteristics are essential for aspiring writers to possess? And what constitutes “good” literature for young people?

Aspiring writers need to be deep readers. They needn’t be fast readers, but they need the reading to create a friction within them that stirs up some desire to write. They need writing discipline, too. There are no tricks to the process. Just set a schedule of reading and writing and stick with it for a few years—by then you should know what you are capable of creating.

I don’t know what “good” literature is for young people. I’m very selective. I like great characters, an engaging story and finely built sentences. I can’t stand reading sentences that are poorly crafted.

Being True to Yourself and Respecting the Reader

Your work doesn’t really fit into the sweet, Pollyanna-type category that much of the literature for young people does. Your characters are flawed. Your stories, especially for young adults and adults, are edgy. What is your reasoning for portraying the angst and trauma of life instead of simply writing happily-ever-after stories?

There is no purpose in writing books that do not fully exhaust all the skills and human qualities of the writer. To write books that are an insignificant extension of myself would be humiliating. If I were not allowed to write the best book I could each time I sat down to do so then I would quit this job and take up another. There is no self-respect in consciously creating insubstantial literature. To do so only denigrates the truth and beauty one expects to create in the reader.

So, is it a conscious decision to incorporate life lessons and real-life issues of growing up and taking responsibility for one’s choices and actions, being a good friend, handling emotions like jealousy and loneliness, accepting differences, and doing the right thing?

Every story is a puzzle in which the reader and writer collaborate in order to find some essential human qualities that, when combined, form a mirror in which the reader can reflect upon himself or herself.

Your biography, Hole in My Life (Square Fish, 2002), portrays a chaotic life during your early years, and that is also reflected in your Jack Henry and Joey Pigza books. Do you believe chaos contributes to creativity?

I have led a colorful life which has allowed me a lot of personal material to write about. That is to my advantage. But writing is not the same as turning on a verbal camera and recording the past. Writing involves finding the perfect words to describe or express a very particular event or emotion and each sentence has to be tailored to seamlessly fit the flow of the narrative. So no matter how colorful your life is, the expression of that life has to be crafted through language. Chaos does not write the books—though it certainly may give birth to them.

As for having a stable life—many writers have had fine writing lives without cataclysmic events buffeting them from one troubling event to another.

Speaking of your biography, it is filled with the angst of finding one’s place and the pain of learning lessons the hard way. Yet, your books for children and middle-grade readers are filled with lively adventures and humorous anecdotes. Why do you believe it is important to not only see but also to recognize the funny in the often not-so-funny parts of daily life—to weave humor with pathos?

When you look at the historic origins of literature, especially Greek literature, you will find that it is when tragic writing and comedic writing fused to become “tragicomedy” that it was found by readers that both moods dramatized the other in a contrasting and engaging way. It is only sensible that every mood and human characteristic be present in satisfying literature that investigates the human condition.

The Rotten Ralph collection sure blends humor and naughtiness well. That cat is truly, truly rotten! Where do these stories come from? Is it true that Ralph is inspired by a cat you had?

Yes, Nicole and I had a cat named Carew who was rotten. But ROTTEN CAREW didn’t make for an attractive title so we changed it to ROTTEN RALPH. As for the source of the stories—each story is based on some human flaw that is exaggerated through Ralph’s extravagantly rotten behavior. But, he is contrite from time to time.

Just like Ralph, your other series characters—Joey Pigza and Jack Henry—are ultimately loveable despite their bad decisions and behavior. As the books convey, these characters are good deep down even if they just look like trouble from the outside. Is that a philosophy you employ in general—that the good is always present in the “bad”?

It is not a philosophy. It is a truth. The human condition is an amalgam of every possible human trait on the positive to negative scale. As a writer, I’m just trying to endow my characters with their own distinct traits on the positive to negative scale and then have those set of traits work to the character’s detriment or success as the story unfolds.

Adding to the Bookshelf

Earlier this year Rotten Ralph’s Rotten Family (Farrar Straus Giroux, 2014) was released, and this fall the last Joey Pigza book is being published. With the conclusion of the Jack Henry and the Joey Pigza series, what is next? What are you working on and what can readers look forward to seeing on shelves and on eReaders in the near future?

Presently I’m working on a memoir titled The Follower and it takes place when I’m fourteen and at a very impressionable stage of my life—when I allowed myself to fully attempt to become a person entirely different than my true self.

Pages from Jack Gantos’ upcoming novel, The Follower.

Speaking of eReaders, there is definitely a trend toward digitizing books. What is your opinion of eBooks? What do you see as the future of printed books?

I figure I may live for another thirty years if I’m lucky. So my future will take me to 2044. I think books will still be relevant then, and always. eBooks will always be around. Audiobooks will always be around. Storytellers will be around. Families will sit around a table and tell the stories of their days. The story itself will always survive the medium in which it is delivered. When the human being no longer has the desire to tell a story then I would be worried.

Fast Facts

“As for fast-facts? That’s about as satisfying as fast-food. I’d rather people read my books and not bother much about me. The books I try to make perfect. As for myself, I’m flawed.”

Books

The Joey Pigza Series

- Joey Pigza Swallowed the Key

- Joey Pigza Loses Control

- What Would Joey Do?

- I Am Not Joey Pigza

- Key That Swallowed Joey Pigza

The Norvelt Books

- Dead End in Norvelt

- From Norvelt to Nowhere

The Jack Henry Adventures

- Jack Adrift: Fourth Grade Without a Clue

- Jack On the Tracks: Four Seasons of Fifth Grade

- Heads or Tails: Stories From the Sixth Grade

- Jack’s New Power: Stories From a Caribbean Year

- Jack’s Black Book

The Rotten Ralph Series

- Rotten Ralph

- Worse Than Rotten, Ralph

- Rotten Ralph’s Rotten Christmas

- Rotten Ralph’s Show and Tell

- Happy Birthday Rotten Ralph

- Not So Rotten Ralph

- Rotten Ralph’s Rotten Romance

- Back to School for Rotten Ralph

- Rotten Ralph Helps Out

- Practice Makes Perfect for Rotten Ralph

- Rotten Ralph Feels Rotten

- Best in Show for Rotten Ralph

- Nine Lives of Rotten Ralph

- Three Strikes for Rotten Ralph

- Rotten Ralph’s Rotten Family

For Older Readers

- Hole in My Life

- Desire Lines

- Love Curse of the Rumbaughs

Awards

- Anne V. Zarrow Award for Young Readers’ Literature, 2014, career award

- Guardian Children’s Fiction Prize longlist, 2012, for Dead End in Norvelt

- Scott O’Dell Award for Historical Fiction, 2012, for Dead End in Norvelt

- Newbery Medal, 2012, for Dead End in Norvelt

- 2010 NCTE/ALAN Award for “Outstanding Achievement in the Field of Adolescent Literature”

- Sibert Honor, 2003, for Hole in My Life

- Printz Honor, 2003, for Hole in My Life

- 2003 Hole In My Life: Winner of the MA ST. Award

- California Young Reader Medal, 2002, forJoey Pigza Swallowed the Key

- Newbery Honor, ALAN, 2001, for Joey Pigza Loses Control

- Iowa Teen Award, Iowa Educational Media Association, Flicker Tale Children’s Book Award nomination, North Dakota Library Association, and Sasquatch Award nomination, all 2000, for Joey Pigza Swallowed the Key

- Great Stone Face Award, Children’s Librarians of New Hampshire, ALAN Notable Children’s Book, NCSS and CBC Notable Children’s Trade Book in the Field of Social Studies, School Library Journal Best Book of the Year, Riverbank Review Children’s Book of Distinction, and New York Public Library “One Hundred Titles for Reading and Sharing,” all 1999, for Joey Pigza Swallowed the Key

- Finalist, 1998 National Book Award for Young People’s Literature, for Joey Pigza Swallowed the Key

- Parents Choice Silver Award, 1999, for Jack on the Tracks

- New York Public Library Books for the Teenage, 1997, for Jack’s Black Book

- Parents’ Choice citation, 1994, for Not So Rotten Ralph

- Children’s Choice citation, International Reading Association, 1990, for Rotten Ralph’s Show and Tell

- Quarterly West Novella Award, 1989, for X-Rays

- National Endowment for the Arts grant, 1987

- Gold Key Honors Society Award,1985, for Creative Excellence

- Massachusetts Council for the Arts Awards finalist, 1983, 1988

- Emerson Alumni Award, Emerson College, 1979, for Outstanding Achievement in Creative Writing

- Children’s Book Showcase Award, 1977, forRotten Ralph

- Best Books for Young Readers citation, American Library Association (ALA), 1976–93, for the “Rotten Ralph” series